Column: Pressure builds on Uber and Lyft under California’s gig worker law

If there were any doubt that California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra and his fellow regulators were getting fed up with the continued flouting by Uber and Lyft of the state’s new gig worker law, it was dispelled by their recent legal motion to force the companies into compliance.

In their June 24 filing, Becerra and the city attorneys of Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco asked a state judge in San Francisco to issue a preliminary injunction ordering the companies to immediately classify their drivers as employees rather than independent contractors.

That’s what’s required by the state’s gig worker law, known as AB 5. “It’s time for Uber and Lyft to own up to their responsibilities and the people who make them successful: their workers,” Becerra said the day the motion was filed.

After eight years of looking the other way, California officials are finally enforcing the rule of law against these so-called gig companies.

— Veena Dubal, UC Hastings School of Law

It should surprise no one that Uber, Lyft and other gig economy companies see it differently and are girding for a fight — including a multimillion-dollar ballot initiative campaign — in which their survival may be at stake.

Designated as independent contractors, drivers are unprotected by minimum wage and overtime rules, receive no workers’ compensation or unemployment insurance benefits, and have to pay for their own gas, insurance, vehicle maintenance and Social Security taxes. They have no right to join or organize into a union.

The dodge of designating employees as independent contractors isn’t new. It was born in the notoriously anti-labor Taft-Hartley amendments of 1947, which first carved out the exception.

Uber, Lyft and Doordash will spend $90 million to undercut a California employment law.

But it has become common in an entrepreneurial economy in which high start-up costs prompt business owners to search out savings in a marketplace in which “employment taxes and other workplace liabilities appear to be low-hanging fruit,” as Elizabeth J. Kennedy of Loyola University in Maryland has observed.

Uber, Lyft and other gig economy companies have exploited America’s lax workplace regulations to build businesses addicted to forcing the cost of business onto the shoulders of essential workers.

Even so, it’s unclear that their exploitation of workers has yielded a sustainable business model. Uber and Lyft acknowledge in financial disclosures that they might never become profitable under current circumstances and that things would become worse if they had to classify their drivers as employees. (Uber has lost $15.7 billion and Lyft $4.2 billion in the last three calendar years.)

Becerra’s action — the latest chess move in a lawsuit he originally filed May 22 — is just one of several prongs California officials have aimed against gig employers over alleged misclassification of employees in recent weeks. San Francisco Dist. Atty. Chesa Boudin sued the delivery service DoorDash on June 16 for classifying its delivery workers as independent contractors.

One week earlier, the California Public Utilities Commission, which had carved out a special regulatory designation for “transportation network companies,” informed the companies that as of last Jan. 1 their drivers “are presumed to be employees” and advised that the law requires them to provide the drivers with workers compensation benefits starting July 1.

Becerra’s action has been lauded as an overdue initiative to protect workers’ rights.

“After eight years of looking the other way, California officials are finally enforcing the rule of law against these so-called gig companies,” Veena Dubal, a labor law expert at UC’s Hastings School of Law, told me. “Because regulators chose not to enforce existing labor laws against the companies, they were allowed to grow precarious work — not just in this state, but all over the world.”

This isn’t a one-sided battle. The companies are fighting Becerra’s lawsuit and, perhaps more consequentially, have placed a measure on the November ballot to overturn AB 5.

Their measure, which will appear as Proposition 22, would effectively designate app-based drivers such as those working for Uber and Lyft permanently as independent contractors and forbid the state or localities to enact ordinances to treat them as employees.

The companies have provided the initiative campaign with a war chest of $110 million so far — $30 million each from Uber, Lyft and DoorDash and $10 million each from Postmates and Instacart, two other delivery services. So it behooves us to take a closer look at the measure.

Proposition 22 attempts to establish a new workplace model — a hybrid of the independent contractor and employment models.

The companies say it would preserve the “flexibility” to set one’s own work days and hours they say is valued by drivers who wish to work around school, caregiving and other work, while guaranteeing minimum pay and access to health coverage.

The measure would guarantee drivers earnings of at least 120% of prevailing hourly minimum wages, a subsidy for health coverage and protection against arbitrary firing.

The companies maintain that the vast majority of their drivers favor remaining independent contractors. Yet that’s misleading because drivers fall into two discrete camps. One is composed of true part-timers who record minimal hours, often abandon the work entirely after a few months, and appreciated the vaunted flexibility. The other is full-time drivers who may be spending 40 to 50 hours a week on the road.

Some 70% to 80% of drivers may drive 20 hours a week or less, says Harry Campbell, a former driver for Uber and Lyft who now runs therideshareguy blog, an information service for drivers. Full-timers, while less numerous, account for more than 50% of the hours worked through the companies’ app.

When it comes to exploiting its front-line workers, the grocery delivery service Instacart may be in a class by itself.

“For a majority of the drivers this isn’t a full-time income, so it shouldn’t be shocking that they want to stay independent contractors,” Campbell says. “But the drivers working 40 to 50 hours a week are basically working like employees without any of the benefits or protections. They’re the ones spearheading the effort to hold the companies accountable to treat drivers like employees.”

And they’re the drivers who would bear the brunt of the changes wrought by Proposition 22. Campbell says, however, that when even part-timers become educated about what AB 5 would do for them and that the law wouldn’t prevent the companies from allowing them some of the flexibility they crave, “some of them change their opinion of the law.”

There can be no doubt that the principal beneficiaries of Proposition 22 would be the companies themselves. If they were forced to classify their drivers as employees, according to the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, the resulting higher costs would “decrease these companies’ long-term profitability, which could reduce these companies’ stock market values and stock prices.”

The measure would impose some new costs on the companies, but those costs would probably be “minor,” the Legislative Analyst’s Office reckons.

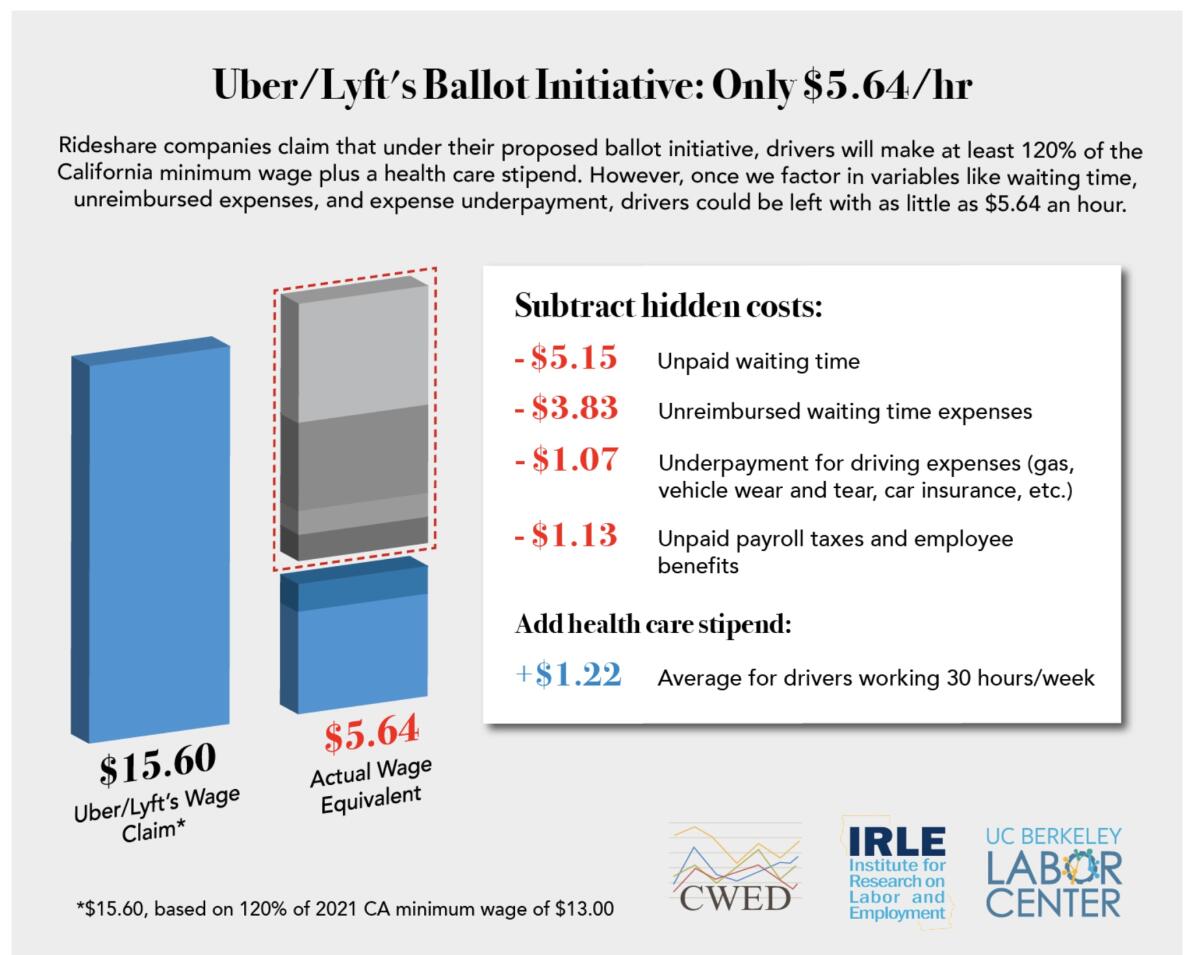

Indeed, the compensation and benefits the companies would pay under Proposition 22 would fall far short of the costs their drivers must shoulder. The UC Berkeley Labor Center estimated in October that 120% of the California hourly minimum wage of $13 in 2021, or $15.60, would effectively shrink to $5.64 an hour because of provisions in the initiative.

Uber’s first-quarter earnings report released Thursday — its first since the ride-hailing company went public on May 10 — disclosed more than the financial condition of the company.

For example, drivers would be paid only for “engaged” time, from when they are en route to pick up a passenger or delivery to when they drop off the rider or package, not for waiting time between assignments. That constitutes as much a one-third of their work time, Berkeley estimated, reducing the $15.60 to only $10.45.

Some drivers would gain from a stipend of up to about $367 a month for health insurance, which could be applied to Affordable Care Act plans from Covered California or other plans. But that would be granted only to drivers averaging 25 engaged hours a week or more. Those with 15 to 25 hours would receive half as much, and those with fewer than 15 hours would receive nothing.

“The vast majority of drivers would not qualify” for the benefit, Berkeley says.

Uber and Lyft have chosen to emphasize the purported consequences of enforcing AB 5, rather than the plain facts of their labor relationships. They , paint a picture of an army of disenfranchised drivers cast aside and unable to ply their trade.

They even hint that AB 5 could put them out of business entirely. Stacey Wells, a spokeswoman for the Proposition 22 campaign, said that if the initiative fails the companies might have to pare their driver ranks, which number as many as 400,000 in California, by as much as 90% to accommodate the added costs of treating drivers as employees.

Yet by any reasonable definition, the companies’ drivers are employees. According to rules set down by the California Supreme Court in a 2018 decision and codified in AB 5, businesses must consider workers employees unless they can meet a three-part test showing that the workers are free from the control and direction of the hiring business, that they’re performing work outside the normal course of the hirer’s business, and they customarily work independently in the same trade or occupation as the work they’re doing.

Becerra maintains that Uber and Lyft can’t meet any of those elements. The drivers are engaged in the companies’ main business of transportation; their compensation is set by the companies, which can change it unilaterally; their performance is monitored by the companies; with the exception of the choice of the hours they wish to drive, all other terms and conditions of their work are set by the companies.

Uber and Lyft have maintained from the start that they’re exempt from AB 5 because they’re not really transportation companies, merely purveyors of the software that drivers and passengers use to arrange rides.

Some courts have dismissed that argument out of hand — “Uber simply would not be a viable business entity without its drivers,” U.S. District Judge Edward M. Chen of San Francisco declared in 2015.

Over the next few months, as the state lawsuit progresses through the courts and election day draws nigh, the survival of the gig companies’ business model will be put to the test. It should not be overlooked how much that model depends on exploiting workers.

“The initiative would codify terrifyingly low labor standards into law,” Dubal says, “undoing over a century of norms around a living wage and safety net protections for workers.”

That’s true. The power of workers to ensure decent working conditions has been on the decline in America for more than half a century. Proposition 22 would hasten the slide.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.