Where to find the most bang for your savings buck. Spoiler: On Wall Street

Dear Liz: I recently sold my home and want to put away funds for my daughters. I want to place $130,000 each in an account that will earn 7% to 10% interest for 30 years or so, providing them with a comfortable retirement fund. I’m thinking of having them start with a low-cost index mutual fund. What are the drawbacks to placing all of the funds in one mutual fund account?

What are the tax implications?

Answer: Stock market index funds mimic a benchmark, such as the Standard & Poor’s 500. That means you’re typically getting at least some diversification, which can help reduce the volatility of your investment.

You could reduce volatility even more by including bond market index funds, or opting for a target date fund that spreads the money across a mix of investments — stocks, bonds, cash. Target date funds are labeled with a specific year in the future and gradually reduce risk as that date approaches. Or you could consider a robo-advisor, which uses computer algorithms and ultra-low-cost exchange-traded funds to create and manage a portfolio.

These investments typically will generate taxable returns, so you’ll want to discuss the implications with a tax pro.

Also, you mentioned earning interest, but interest is what is paid on bonds and savings accounts. Returns are what investors earn on stocks and other higher-risk investments. No investment currently pays 7% to 10% interest. Over time, stocks typically generate average annual returns of 8% or so, but returns aren’t guaranteed and some years your stocks may lose money.

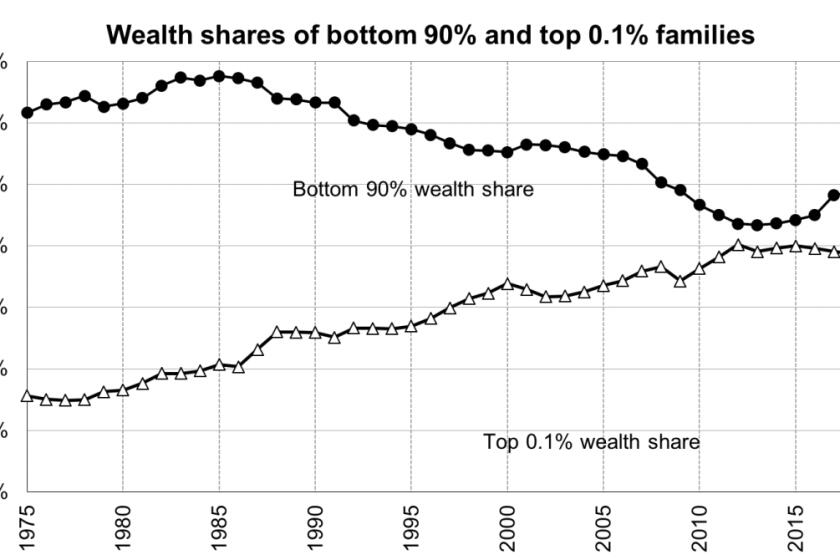

It’s widely assumed that the biggest tax scofflaws are those with the most money. A new study tells us things are much worse than anyone suspected.

Roth IRA contributions

Dear Liz: I am a retired public employee and receive most of my compensation in monthly payments, for which I get a 1099R form at tax time. The rest of my compensation also comes in monthly installments and I receive an annual W-2 for that. My question is: Can I deposit my W-2 amount in a Roth IRA?

Answer: You must have earned income to contribute to an IRA or Roth IRA — which you apparently have, since you’re getting a W-2 form from an employer. Your ability to contribute to a Roth begins to phase out with adjusted gross income of $125,000 if you’re single or $198,000 if you’re married filing jointly.

Assuming you’re 50 or older, you can contribute a maximum of $7,000 or 100% of what you earn, whichever is less.

Despite a pandemic that has upended industries and resulted in massive job losses, bankruptcy filings are down.

Backdoor Roth Ira conversions

Dear Liz: I am 65, self-employed and have a SEP IRA as well as a Roth IRA. I’ve had a few low-income years, and I find myself in a very low tax bracket, most likely lower than when I begin to take distributions and collect Social Security in a few years. What are the steps for a “backdoor Roth” conversion? As a self-employed person, do I even qualify?

Answer: A backdoor Roth is a way for higher-paid people to get around the income limit for Roth contributions. If you’re in a low tax bracket, that limit likely isn’t a problem for you.

What you’re probably asking about is a basic Roth conversion, where you roll money from your pre-tax SEP IRA into a Roth and pay the resulting taxes. Such conversions can make sense if you expect to be in a higher tax bracket later and you don’t have to tap your account to pay the taxes, but they’re not a slam dunk.

A too-large conversion could push you into a higher bracket. or increase your Medicare premiums or both. (Higher Medicare premiums are imposed when modified adjusted gross incomes exceed $88,000 for singles or $176,000 for married couples filing jointly.)

Financial planners often recommend converting just enough to “fill out” a low tax bracket. Let’s say you’re single and currently in the 12% federal tax bracket, which ends at $40,525. If your income is $25,000, you might convert about $15,000 of your SEP to avoid being pushed into the next bracket, which is 22%.

A tax pro or fee-only financial planner could advise you about how to proceed.

Liz Weston, Certified Financial Planner, is a personal finance columnist for NerdWallet. Questions may be sent to her at 3940 Laurel Canyon, No. 238, Studio City, CA 91604, or by using the “Contact” form at asklizweston.com.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.