Column: Jeff Bezos likes Biden’s infrastructure plan because he knows it’s worth the money

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos turned quite a few heads Tuesday when he came out in favor of President Biden’s $2-trillion infrastructure plan and even endorsed Biden’s proposal to raise corporate taxes to pay for it.

“We support the Biden Administration’s focus on making bold investments in American infrastructure,” Bezos wrote on his company’s website. He added, as explicitly as you’d wish, “we’re supportive of a rise in the corporate tax rate.”

For those hankering to find the devil in the details, it’s proper to note that Bezos’ endorsement wasn’t entirely unconditional.

After decades of disinvestment, our roads, bridges, and water systems are crumbling. Our electric grid is vulnerable to catastrophic outages. Too many lack access to affordable, high-speed Internet and to quality housing.

— Biden infrastructure plan

“We recognize this investment will require concessions from all sides — both on the specifics of what’s included as well as how it gets paid for,” he wrote.

Yet no one should be too surprised that, on balance, Bezos is on board. The Bezos statement acknowledged, explicitly or otherwise, a few truisms about public infrastructure-building in the United States.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

One is that these projects more than pay for themselves. That’s been the record of public works projects dating back to the 19th century.

Another is that only the government can accomplish much of this construction, because the program is generally too big or its benefits too diffuse or conjectural to attract private sector investment. But once the projects are built, the benefits redound to private enterprise.

A third is that companies such as Amazon don’t have to worry about increases in the corporate tax rate, because they don’t pay anywhere near that rate.

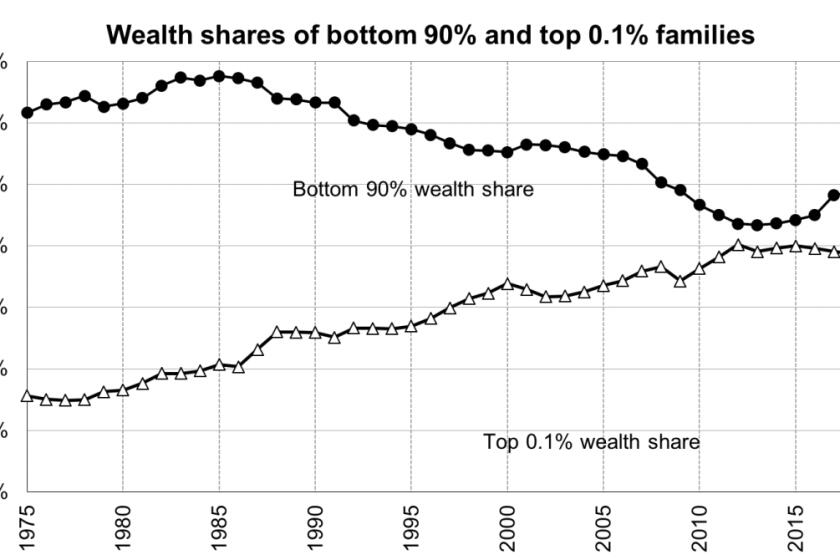

In 2020, Amazon paid $1.84 billion in federal income taxes on its profit of $20.2 billion. That’s a tax rate of about 9.1%, well below the statutory corporate rate of 21%. In 2019, its effective tax rate was 1.2%, and in 2018 it got a tax refund of $129 million.

A corporate tax proposal released by the Treasury Department on Wednesday calls for raising the corporate rate to 28% and imposing a minimum tax of 15% on “book income” — profits reported by corporations before certain tax deductions. The Treasury says that about 45 companies with more than $2 billion in profit would have paid the minimum tax in recent years.

Whether Amazon would have been among them is unclear, but given the discrepancy between its tax rate and the statutory rate of 21%, that’s a good bet. (Bezos hasn’t specified what corporate tax rate he’d consider acceptable.)

Laying that aside for the moment, let’s look at the potential impacts for Americans generally from the Biden plan.

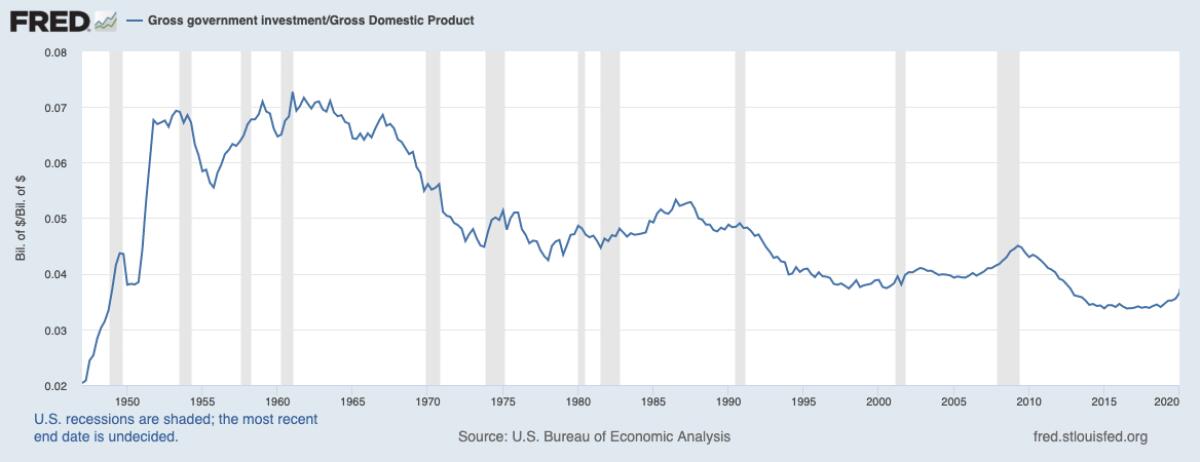

Via Twitter, Erik Brynjolffsson of MIT posts a graph similar to the one above and asks: “Why is public construction plummeting?

Biden’s program has been the target of a tsunami of fatuous discussion over what properly qualifies as “infrastructure.” Some conservatives argue that only physical structures, especially transportation projects such as roads, bridges and airports, are “infrastructure.”

That would exclude such items in the Biden plan as broadband access, modernization of schools, child-care facilities, Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals and other federal buildings.

It would also leave out tax credits for clean energy generation and storage as well as refashioning America’s electric grid to reflect the shift in power sources from fossil fuel plants to wind and solar facilities.

Also on the hit list would be Biden’s proposal for $180 billion in enhanced funding for government research agencies such as the National Science Foundation and for academic laboratories.

“After decades of disinvestment, our roads, bridges, and water systems are crumbling,” the Biden administration says. “Our electric grid is vulnerable to catastrophic outages. Too many lack access to affordable, high-speed Internet and to quality housing.”

Conservatives like to denigrate many of these projects as Democratic Party slush. Here’s Kevin D. Williamson of the National Review, sneering that “this kind of project presses all sorts of New Deal, TVA, rural-electrification buttons in Democrats of Joe Biden’s generation.”

But here are the facts: The New Deal kept millions of Americans out of poverty during the Great Depression and bequeathed us untold projects still in use, including New York’s LaGuardia Airport and Los Angeles International Airport.

The Tennessee Valley Authority, which included reforestation of barren hillsides, construction of flood-control reservoirs and dams and the dredging of a ship canal from one end of the valley to the other, lifted one of America’s poorest regions out of destitution.

Before the TVA, 1 farm in 100 in the valley had electricity, and the average per capita income was half the national average; the TVA turned the valley into a leading American industrial region. More broadly, rural electrification transformed daily life in the countryside for the better. Much better.

The opponents of such projects were generally entrenched business interests. Utility companies, for instance, groused that they should have the right to provide residents with power — except that they hadn’t been doing so except at usurious rates.

The truth is that all Biden’s ideas fall squarely within the traditions of American public spending, and the benefits are incontrovertible, as are the drawbacks of disinvestment. Without government financial investment there would be no Hoover Dam today and no interstate highway system.

It’s widely assumed that the biggest tax scofflaws are those with the most money. A new study tells us things are much worse than anyone suspected.

Federal investment as a share of the economy has collapsed since the early 1960s, when it accounted for more than 7% of gross domestic product. Today it’s about half that.

The U.S. was once a global leader in scientific research spending. R&D accounted for as much as 12% of the federal budget in the 1960s; by 2019 it had fallen to 2.8%.

As a result, according to a 2015 report by MIT, of four landmark scientific achievements the previous year — the first spacecraft landing on a comet; the discovery of a new fundamental particle, the Higgs boson; the development of the world’s fastest supercomputer; and research pointing to new ways to meet global food needs — not one was a U.S.-led program.

Many business leaders like Bezos have learned their lessons from the earlier phase of government investment. Government-funded projects eventually yield profits for the private sector and benefits for society as a whole.

Individual companies would never have taken on the task of building a nationwide highway network. But the interstate system, begun under Dwight Eisenhower in 1956, has cut travel times coast to coast — and therefore the cost of shipping — by more than one-third.

According to a 2016 report by the American Society of Civil Engineers (which admittedly has a vested interest in public construction) the interstate system, which cost $500 billion in 2016 dollars to build, has produced $6 in economic gains for every $1 spent.

Development of the internet was hobbled by the communications monopoly owned by AT&T, which refused to allow data to pass through its phone lines. That prompted a visionary official at the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency named Bob Taylor to take matters into his own hands. Taylor funded a computer data network initially known as ARPAnet, the offspring of which is the internet.

Pundits like Williamson mock Biden for listing broadband access as crucial infrastructure, but that’s a pronouncement from a privileged rooftop. “By industry estimates,” he writes, “about 93 percent of Americans have access to a broadband connection, and those who don’t mostly live in remote and rural areas.”

This is an old industry scam of playing with the definition of “access” — those homes may theoretically have access, but monopolistic pricing keeps it out of their hands. Williamson’s argument that those who want better service can just move to the cities doesn’t warrant serious consideration.

Broadband access today is necessary for daily life almost anywhere you live. Indeed, lack of access has been used to disadvantage low-income communities.

Arkansas, for instance, required residents subject to its work mandate for Medicaid eligibility to report regularly via a state website. But less than 55% of all residents have access to broadband, and in some low-income counties the level is less than 10%. (This was one reason that a federal judge overturned the state’s work rules.)

The U.S. lags many other developed countries in the average speed of its broadband access, and prices here are higher than in much of the rest of the developed world. Who says so? The Federal Communications Commission.

In a 2018 report, the FCC ranked the U.S. 10th out of 28 comparable countries in the average speed of its fixed broadband service, 24th in mobile download speeds, and 26th in the price of a broadband connection with a reasonable speed of at least 100 megabits per second.

A new report from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology lists four landmark scientific achievements of the last year: the first spacecraft landing on a comet; the discovery of a new fundamental particle, the Higgs boson; the development of the world’s fastest supercomputer; and new research in plant biology pointing to new ways to meet global food needs.

The reason for this dismal record isn’t hard to discern — it’s because the U.S. government has ceded broadband development to private companies, which provide more affluent neighborhoods with the best service and, since much of the country has only one or two competing providers, can effectively charge monopoly prices. A government investment to counteract this sort of rent-seeking by private enterprise is desperately needed.

Bezos knows that government infrastructure spending means money in Amazon’s coffers. Better roads and other transport infrastructure reduce Amazon’s cost to deliver merchandise to customers, and better broadband penetration means more customers for its online service. So he left open the question of what varieties of “infrastructure” he likes, and what he’d be happy to dispense with.

The remaining question is how to pay for Biden’s program. With interest rates still hovering at historical lows, it would be cheaper for the government to fund the program through borrowing than at almost any time in the postwar period.

As for raising the corporate tax rate, America’s CEOs might object, but let’s recognize that for many big corporations the statutory corporate tax rate is merely theoretical.

As the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy has documented, 55 major corporations paid zero income tax on their profits in 2020. Among them were several that are dependent on government-funded transportation and digital infrastructure, such as FedEx and Charter Communications.

These companies are well practiced at taking advantage of tax breaks and loopholes in the law. Amazon, for example, makes liberal use of deductions for stock-based compensation, which has saved the company more than $3 billion in taxes in just the last three years. Unspecified “tax credits” saved an additional $1.5 billion.

For decades, America has been shortchanged by politicians demanding austerity in government budgets by labeling “investment” as “spending.” The deficit in the condition of the country’s infrastructure has grown relentlessly.

Biden is right to demand that the trend be reversed. His critics maintain that his vision is too broad, too imaginative. But when you’re mapping out the future, what’s wrong with imagination?

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.