Column: America is not facing a civil war — only loudmouthed extremists

With an election just behind us and another beckoning a year from now, political pundits are dusting off their perennial observations about a “polarized” America.

Actually, these observations don’t need to be dusted off because they’re never put on the shelf, no matter how wrong they’re proved by actual facts. The truth is that America is nothing like a polarized country.

Large majorities agree on the most pressing issues of the day: They favor abortion rights, stricter gun controls and more COVID-related restrictions, especially on unvaccinated people. You might not be aware of this if you listen to programs on Fox News or even the average political commentary in our leading newspapers or on CNN.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, many Republicans were behind efforts to liberalize and even decriminalize abortion...while Democrats, with their large Catholic constituency, were the opposition.

— Sue Halpern, New York Review of Books

There, depictions of an America wracked by irreconcilable disagreement is daily fare.

But they’re not reporting a genuine schism in American politics; they’re reporting on a divide pitting a majority in broad agreement against a boisterous minority. The latter’s footprint is magnified through the platforms provided by Fox News, Facebook and other information outlets that don’t care to report facts but prefer trading in conflict.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Sometimes you even hear the prospect of a new “civil war” being waged in the U.S. William G. Gale and Darrell M. West of the Brookings Institution raised precisely that specter in a recent essay.

Gale and West pointed to increasingly intemperate and even violent rhetoric mouthed by some of our least responsible politicians (Madison Cawthorn, I’m looking at you), as well as America’s divides in race, gender, wealth and economic opportunity. But the latter have long been with us, and the fact that they’re now more openly acknowledged is a positive development, not grounds for fear.

Gale and West acknowledged that most of the divisiveness is generated by small, fringe individuals and groups. “Still,” they wrote in a weirdly halfhearted gloss, “civil war is not inevitable.”

One indication that chatter about America’s perilous divide may be overwrought came just this past weekend, when a highly touted rally scheduled for Washington to support the Jan. 6 insurrectionists turned into a comic-opera flop, with rallygoers apparently outnumbered by journalists.

Corporate America has been almost silent on a Texas law that bans most abortions and promotes vigilantism. That’s no surprise when its own interests are at stake.

“Emotions ran tepid,” wisecracked the New Republic.

The image of a deeply divided America has infected political analysis. Consider the conclusions being drawn from the most recent American election, the failed Sept. 14 recall attempt against California’s Democratic governor, Gavin Newsom.

Jonathan Martin of the New York Times, for example, concluded that Newsom’s victory pointed to a California more “polarized” than it was during the previous recall vote, in 2003, which brought Arnold Schwarzenegger to the governorship.

Martin validated his picture of an increasingly polarized California by noting that in the presidential campaign just preceding that recall, Republican George W. Bush lost to Democrat Al Gore in California by only 11 points, while last year Donald Trump lost to Joe Biden by a whopping margin of nearly 30 points.

Martin needs to check the dictionary definition of “polarized”: Trump’s losing California by a margin three times larger than Bush’s loss shows a state much less polarized than in 2000. Biden’s 63.48% victory, by any definition, is a landslide, which is exactly what you don’t get from a polarized electorate.

Newsom’s defeat of the recall by 63% to 37% (according to the latest election results) was significantly larger than the recall vote in 2003, a 55.4%-44.6% vote to remove Gray Davis, who was an epically unpopular governor. That’s another indication that California is much less polarized now than it was then, not more so.

Martin isn’t alone among out-of-state pundits in describing California as a “deeply liberal state.” They all need to spend more time in California before making such a shallow generalization.

California isn’t so much a “liberal” state as a Democratic Party state. Its voters have been known, as recently as last November, to turn away manifestly liberal initiatives, such as one that would have made the criminal justice system more equitable by doing away with cash bail, a liberal goal for years.

The difference between “liberal” and “Democratic” can be vast. That’s important in judging political reality. The Democratic Party reigns in California largely because its Republicans have long since ceased to offer cogent or even respectable solutions to its many problems.

Over the last 20 years, Democratic voter registrations have gained only modestly, rising to 46.1% last year from 45.4% in 2000. The major change is that GOP registrations have plummeted, to 24.2% last year from 34.9% in 2000. The independent category picked up the slack.

What that tells you is that Democrats have held their own, but Republicans have moved sharply away from the public’s values. That, again, isn’t polarization so much as simply one party leaving the contest.

“Today is that terrible day you pray never comes,” Sen.

The same misconceptions govern political issues on the national scale. Before getting into those details, let’s be sure we understand what “polarization” means.

Polarization suggests a 50-50 split on a topic, not 60-40. In the first situation, it’s hard to find a common ground; in the second, a common ground has been reached — it’s the ground where that 60% majority lives.

The biggest landslide victory in a presidential election since 1824 belonged to Lyndon B. Johnson in his 1964 race against Barry Goldwater, and LBJ secured only 61.05% of the popular vote. Even Franklin Roosevelt, in his historic drubbing of Alf Landon in 1936, got only 60.8%. That tells you that America has almost always been a 60-40 nation, and it still is today.

It’s proper to note that majority rule, while a valuable principle in general, should have its limits; the minority side shouldn’t be ignored in the making of public policy. Certainly public positions that started out as minority-held eventually moved into the mainstream: civil rights, gay marriage, opposition to the Vietnam War, among other things.

The problem arises when extremist views that are manifestly inimical to the public welfare are afforded outsized respect. It’s often hard to judge where the line is, but opposition to abortion rights, to stricter gun control, and to anti-pandemic measures ranging from mask rules to vaccination mandates crosses it. The majority view in all those cases is devoted to augmenting public health — it’s inclusive, not exclusionary.

Let’s look at how Americans line up on those issues. Start with abortion rights. About 60% of all Americans feel that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, according to a survey released in May by the Pew Research Center. That’s almost exactly where sentiment rested in 1995.

What changed is that Republicans made abortion a litmus test for GOP orthodoxy. It wasn’t always so. As writer Sue Halpern observed in 2018, it was the result of a conscious strategy by Richard Nixon and his minions to lure Catholic voters away from Democrats and into the Republican Party.

“In the late 1960s and early 1970s,” Halpern reported, “many Republicans were behind efforts to liberalize and even decriminalize abortion; theirs was the party of reproductive choice, while Democrats, with their large Catholic constituency, were the opposition.”

Nixon’s strategy overturned a long-held GOP position. As California governor in 1967, Ronald Reagan signed one of the most liberal abortion laws in the country, legalizing the procedure when a mother’s mental or physical health was at stake or in cases of rape or incest. At that time, Halpern reports, “Richard Nixon, Barry Goldwater, Gerald Ford, and George H.W. Bush were all pro-choice, and they were not party outliers.”

Once Nixon demonstrated that anti-abortion politicking could bear fruit, the rest of the GOP fell into line. The harvest is the gruesomely malicious abortion laws now being enacted in red states.

A bogeyman in the debates over Obamacare, death panels have arrived for real in Idaho after lax anti-COVID measures hobbled hospitals.

Now let’s examine gun control. Here, too, the American public favors more restrictions on gun ownership; according to the Gallup Poll, 57% think gun laws should be made more strict and only 9% think they should be loosened.

Here, again, one would not know this from the braying of the Republican minority about “2nd Amendment rights” and the trigger-happy posturing of GOP politicians such as Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia and Lauren Boebert of Colorado. Could these people win an election anywhere but in their home districts? Possibly, but to paraphrase Mark Twain, that’s not the way to bet.

Finally, let’s consider COVID-19, vaccinations and rules for social distancing. Opposition to shots and mask-wearing may be the most confounding minority campaigns in the U.S., because the consequences of undermining vaccinations and masks can be counted in thousands of lives, with the evidence staring us, as it were, in the face.

The Pew researchers found that most adults are aware that pandemic-related restrictions have hurt businesses and kept people from living their lives however they want — no reasonably conscious person could think any differently. But 73% believe the restrictions have reduced hospitalizations and deaths, and 72% that the restrictions have helped to slow the spread of the virus.

Most important, nearly two-thirds of those who believe the restrictions helped slow the spread of the virus believe the restrictions are worth the cost.

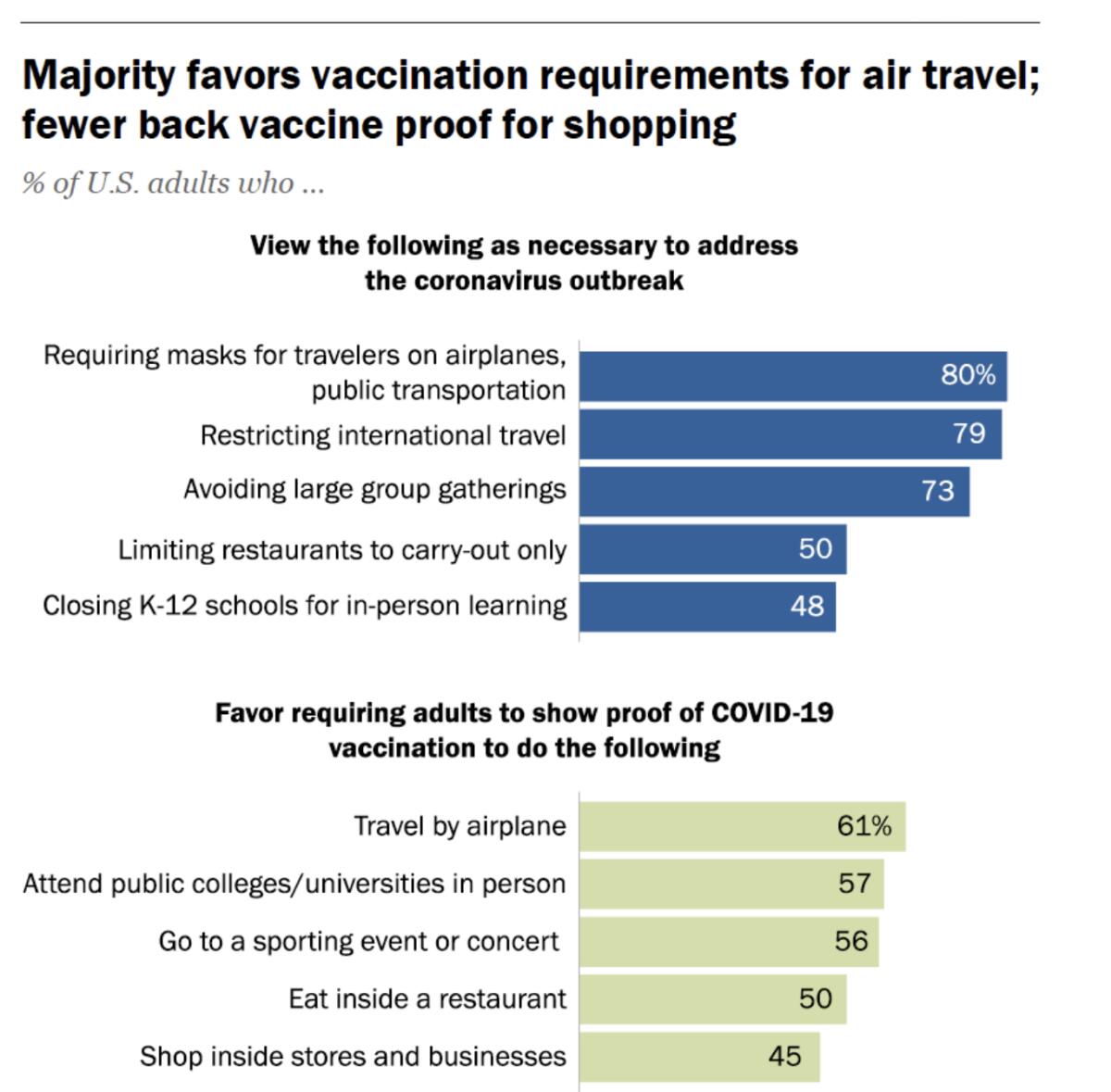

The vast majority of poll respondents (80%) favor requiring masks for travelers on airplanes or public transportation. Strong majorities favor requiring proof of vaccination for travel by plane (61%) or to attend a sporting event or concert (56%).

Measure that against the claims of Republican office-holders throwing fits about President Biden’s call for vaccination mandates or retail shoppers carrying on about infringements of their “freedom.” Most Americans appear to agree that public health and safety depend on broad cooperation with anti-pandemic measures.

Politicians who have bet their futures on siding with a smaller subset of Americans on all these issues — and they are almost invariably Republicans — may want to rethink their strategy. Signs are beginning to emerge that the public isn’t going along.

Two GOP governors most closely identified with right-wing policymaking, Ron DeSantis of Florida and Greg Abbott of Texas, have recently seen their popularity slip. DeSantis’ net approval rating has fallen 14 percentage points and Abbott’s has fallen seven points since the beginning of July, according to Morning Consult.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020, Abbott’s approval rating was 59%, according to the Dallas Morning News, which says “it’s been dropping since January and is now at a rock-bottom 45%.” Among independents, the newspaper’s most recent poll found, Abbott’s right-wing policies have driven his approval from 53% last year to only 30% now.

Both governors remain popular among Republican voters, which may save them if those voters turn out more than Democrats or independents.

The public has spoken on most of the issues of the day, and the call is for more abortion rights, fewer gun rights, and more action to preserve public health in the teeth of a pandemic.

The recent California recall did send a signal that Democrats should heed: They don’t represent one camp in a fragmented union, but a populace that has made its priorities clear. The way to silence that noisy, swaggering, ranting camp that wants to overturn those priorities is to confront it, head-on.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.