Is the ports logjam really getting better? The numbers don’t tell the whole story

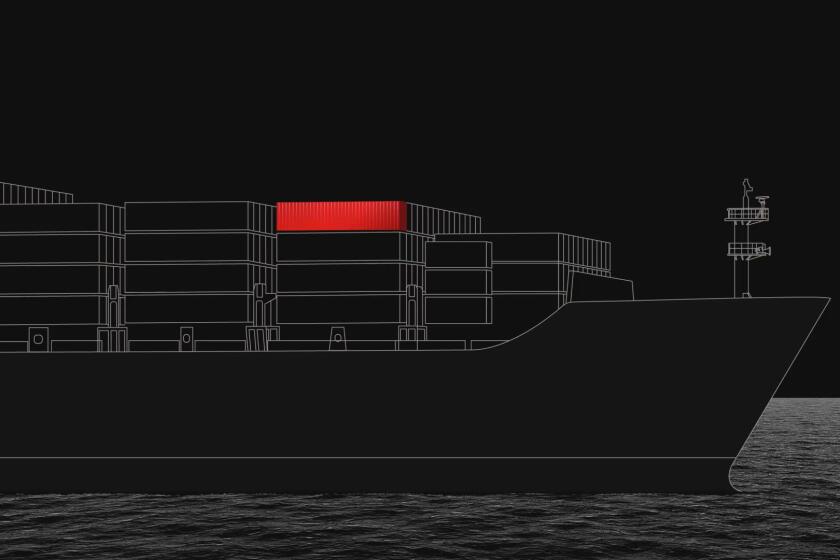

San Pedro Bay is looking less crowded these days. The fleet of massive container ships loitering just offshore from the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles has thinned to 46 boats from its peak of more than 80 in late October.

Is that a good sign for Southern California’s congested supply chain, and the breathability of its air? That depends on who you ask.

At a news conference Tuesday to mark Labor Secretary Marty Walsh’s first visit to the port complex, Port of Los Angeles Executive Director Gene Seroka pointed to the drop in ships at anchor as a sign of progress. “Since we instituted a penalty for long-aging containers, the number of ships at anchor has decreased by more than 40% over a four-week period,” Seroka said.

The implication had some supply chain watchers blowing their stacks. The dwindling number of ships directly offshore can’t be disputed — but the total number of vessels waiting hasn’t gone down because the ports have suddenly sped up operations.

“It’s an apples-to-oranges comparison,” said Sal Mercogliano, professor of maritime history at North Carolina’s Campbell University and a former merchant mariner who criticized the comment on social media.

The logjam at the ports and larger supply chain disruptions have led to record-setting profits for big companies in the logistics business.

The dramatic decline in the number of ships at anchor stems from a new policy set by shipping trade groups that encouraged incoming ships to wait out in the open ocean rather than close to shore. Starting Nov. 16, boats crossing the Pacific have been asked to sit 150 miles offshore as they wait for a slot to unload their cargo, and boats traveling north or south along the coast were asked to sit 50 miles out. Although only 46 ships were waiting in San Pedro Bay as of Wednesday, an estimated 50 additional container ships that embarked after the change are now loitering over the horizon, which would raise the total backlog to a record high.

Seroka “is an expert in the field, and what L.A. and Long Beach have been able to do is amazing in terms of cargo,” Mercogliano said. But he saw conflating the number of boats nearby with the total backlog as “a little disingenuous.”

In an interview, Seroka defended his statement with some clarification. Four weeks ago, 84 boats were waiting at anchor to be unloaded. More than 40% of those 84 boats have been unloaded since, Seroka said, which he cites as evidence that the ports are working at an impressive pace, even if the backlog continues to grow at sea.

The ports have handled record-setting cargo volumes over the last year, though they’ve hit a plateau. “Before the pandemic and before the surge in the American consumer buying patterns,” Seroka said, “during the peak season we would have one or two months where we move 900,000” twenty-foot equivalent units — or TEUs, the standard volume metric in ocean shipping — all told, including loaded imports and exports and empty containers.

“We’ve been averaging 900,000 containers a month for 17 months now,” Seroka said. “This is really peak performance.”

The Port of Long Beach has been working at a similar clip, with its monthly throughput hovering around 800,000 TEUs over the same period.

The week of Thanksgiving showed a slowdown at the L.A. port, with only 63,000 TEUs unloaded, but the port is back to full capacity this week, Seroka said, and he believes that that number can go higher in coming months.

The cities of Los Angeles and Long Beach serve as landlords to the ports, and private companies run the boats, terminals, trucks and warehouses. Seroka, as the leader of the Los Angeles side of the operation, has limited power to make changes on his own, but he sees a few shifts that could speed things up.

Follow a container of board games from China to St. Louis to see all the delays it encounters along the way.

Warehouses, trucking companies and the terminal operators could start running more night shifts, which would move more containers out when traffic is lighter. The Biden administration could reexamine some of the tariffs on Chinese imports that the Trump administration put in place — specifically, Seroka said, the tariff on importing truck chassis to move containers, which has contributed to the bottlenecks at the ports by making chassis a rare commodity. And the shipping companies could collaborate more closely to get empty containers, which are taking up real estate necessary to unload new ships, off the docks.

Seroka said he has seen some progress on this last point. One of the many kinks in the supply chain is that smaller shipping companies that previously worked regional routes in Asia have gotten into the transpacific business as demand and freight rates skyrocketed this year. As newer entrants to the field, these shippers had contracts to bring goods east to the U.S. from Asia but hadn’t established an export business for the route back — meaning they would simply steam away once they unloaded their ships. Now, some of these companies are striking deals with the big players in the industry to take back their empty containers on the westward route.

Seroka also insisted the new queuing system that puts ships 50 or 150 miles offshore is a step forward in efficiency rather than a cosmetic change. Under the old system, ships could get in line to unload their cargo only when they were within 20 miles of the ports. That meant that ships had to race across the sea, burning extra fuel in the process, to secure their spot in line, only to sit and wait for weeks on end once they arrived.

The change gives the ports a better idea of what’s coming their way, reduces overall emissions by slowing the boats down, reduces emissions close to the coast because the vessels are farther out to sea, and, Seroka said, reduces the danger of ship collisions in San Pedro Bay.

“We had a wind event about four weeks ago, and it scared the daylights out of all of us” when 50- to 60-mile-per-hour winds started pushing boats around, Seroka said.

The organizations that created the new system — the Pacific Merchant Shipping Assn., Pacific Maritime Assn. and the Marine Exchange — emphasized the environmental effects of the shift when they announced it in early November, as air quality in the L.A. area declined and calls for regulating emissions from the shipping industry intensified.

It’s time for air quality officials to drop the hammer and regulate pollution from the ports of L.A. and Long Beach, where a jam of diesel-spewing cargo ships has nearly doubled emissions during the pandemic.

“This process will allow vessels to slow their speed and spread out, reducing vessels at anchor before the onset of winter weather, in addition to reducing emissions near the coastline,” they wrote in a statement announcing the creation of the Safety and Air Quality Area.

The California agencies that regulate air quality said that they were not consulted on the shift before it was announced, though they are cautiously optimistic that it could help improve the situation.

“We have not specifically looked at the air quality impacts associated with this change,” Michael Benjamin, chief of the California Air Resources Board’s air quality planning and science division, said in an email. Although he said that the change “should be a positive from an air-quality perspective because it significantly dilutes pollution before it reaches the coast and populated areas,” he noted that the shift “does not take away from the need to clean up the fleet serving California ports.”

A recent CARB report found that emissions at the ports increased 75% since 2019 from the heavy traffic, with the surge in shipping contributing an additional 20 tons of smog-producing nitrogen oxides a day and other activity contributing an additional 7 tons a day. The same report found that particulate matter emissions from ships at the port surged from an average of only 0.0002 ton a day before the congestion began in mid-2020 to half a ton daily in September and October 2021 — a 2,500-fold increase equivalent to adding 100,000 heavy-duty diesel freight trucks to the road.

Regulators at the South Coast Air Quality Management District agreed that if anchored vessels are kept 150 miles offshore, they expect to see an air quality benefit — though that could be partially offset by an increase in emissions from ships needing to run their engines to navigate out at sea.

“We do not yet know what the net impact or benefit of these potentially higher emissions would be for our region’s air quality,” agency spokesperson Nahal Mogharabi said.

Although the dwindling number of ships in San Pedro Bay is an encouraging sign, “the anchorages closest to shore all appear to be essentially full, and those closer-in ships would be expected to have the greatest impact on air quality,” Mogharabi said. “The significant backup of ships beyond 150 miles also indicates that we should expect higher port emissions in the foreseeable future.”

The container fleet may be out of sight, but it’s not out of mind. And the ports will probably continue to be a bottleneck for U.S. imports for months to come.

“We’ve got to keep working,” Seroka said. He expects that activity will remain at a high level through the early months of 2022 as U.S. companies seek to build up their depleted inventories after the holidays. “We need to get this stuff synchronized” across the many public and private actors in the supply chain, he said, to make a bigger dent in the mounting backlog. “But we’ll take the small wins.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.