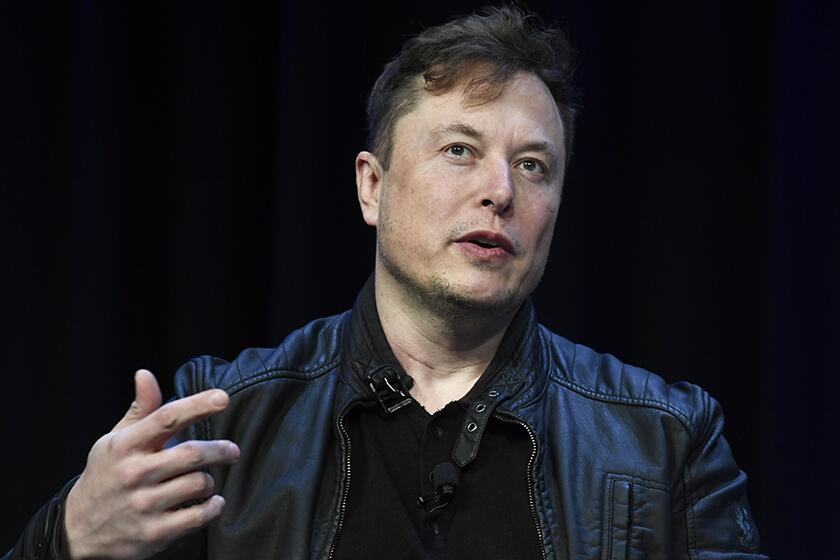

News Analysis: ‘Free speech absolutist’ Elon Musk has a long history of opposing speech and transparency

Elon Musk might be serious about taking over Twitter. Or his hostile bid might be just a rich man’s whim, a distraction he’ll abandon when it begins to bore him. Or maybe he’s punking everybody.

Because it’s Elon Musk, it’s hard to tell. Yes, he transformed the automobile industry with electric-car maker Tesla. His rocket ship company, SpaceX, reinvigorated an industry long dominated by plodding defense contractors such as Lockheed and Boeing. Remarkable accomplishments both.

But he’s been sued for defamation, has defended himself by saying no one takes him literally and was fined by the government for making fraudulent business claims. On Twitter, where he regales his 80 million followers with a 24/7 stream of pure Musk, he’s fashioned himself into a jokester, a provocateur, and, when the mood suits him, a clown.

In literary terms, he’s what you’d call an unreliable narrator.

In his bid to buy Twitter, he opened with a flourish that suggested levity, working the number “420” into his proffered share price. The weed joke evidently fell flat: The board created a “poison pill” provision to deter him.

Now, in need of support from shareholders and potential financiers, he has turned to rhetoric, laying out a grand if fuzzy vision for the Twitter he would build.

Calling himself a “free speech absolutist,” he said he wants to make the social network what he regards as a friendlier place for free expression by “being cautious about” permanent bans and loosening its content restrictions. “A social media platform’s policies are good if the most extreme 10% on left and right are equally unhappy,” he tweeted Tuesday.

He also said he would make Twitter transparent about its inner workings, open-sourcing the algorithm it uses to sort and amplify tweets so it’s no longer a “black box.”

How seriously should such talk be taken? Rather than try to parse his words — always a fool’s errand — perhaps it’s best to answer that by looking back at his record as a chief executive.

Start with transparency. According to Musk, Twitter posts are “mysteriously promoted or demoted with no insight into what’s going on” and who or what is making the decisions. “Having a black box algorithm promote some things and not other things, I think this can be quite dangerous,” he said at the TED conference last week. He suggested posting Twitter code on the open source developer site GitHub.

The billionaire leader of Tesla and SpaceX says Twitter must go private to fulfill its “societal imperative.” But the way he went about offering to buy it left Wall Street doubting his seriousness.

There’s some irony around Musk’s critical use of the term “black box.” Tesla has its own algorithmic black box in its cars — the one responsible for automated driving.

Like Twitter’s algorithms, the code governing the operation of Teslas in Autopilot or Full Self-Driving mode is private and proprietary. That has made it difficult for regulators to understand the specific failures that have led to Teslas steering themselves into parked emergency vehicles, running down railroad tracks, confusing the moon for a traffic signal yellow light and other documented mistakes.

Also closely guarded are Tesla’s data on Autopilot injuries and fatalities. Musk says cars driven on Autopilot are safer than those driven by human drivers, but he has never served up the proof. University researchers have offered to evaluate the data while keeping it shielded from public view. Musk has never responded to their offers.

“We would like him to be a little more transparent with respect to the safety of his Teslas,” said Alain Kornhauser, who heads the autonomous vehicle program at Princeton University. “A lot of us think they’re safe. We’d like to do an independent evaluation and offer a second opinion. I think it would help him and help the world.”

To get details on a car’s performance before and after a crash, Tesla owners, police and lawyers have had to have a subpoena issued to compel the company to share data.

Musk has also bristled at the transparency requirements that come with being a public company CEO, time and again directing taunts and vitriol at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which is charged with regulating securities markets and protecting investors. In one profane tweet, he suggested that the E in SEC stands for “Elon’s,” a message universally interpreted as an invitation to the agency to perform a sex act on the mega-billionaire.

In the buildup to his Twitter bid, Musk was still thumbing his nose at the agency, dragging his feet in filing a mandatory disclosure form announcing his purchase of a stake greater than 5%. That led to a lawsuit accusing him of ripping off other investors and pocketing the gains by building up his stake still further before the news broke, sending the share price up. Meanwhile, he’s back in court trying to overturn a 2018 settlement with the SEC on fraud charges.

Musk did not reply to requests for comment. Almost alone among major public companies, Tesla does not have a media relations department.

Then there’s the question of Musk’s alleged free-speech absolutism. When it comes to the speech of others, particularly his employees and critics, his commitment has been anything but absolute. Far from defending their right to speak up, he has sought to stifle them with legal muzzles or responded with firings, lawsuits or even the hiring of private detectives.

Cristina Balan, who raised alarms about vehicle safety while working as an engineer at Tesla, is one of several whistleblowers who has encountered Musk’s wrath after going public. Shortly after scheduling a meeting with Musk to make her case, she was fired, and the company began slipping false information about her to a reporter. Balan’s defamation case against Tesla is still in the courts. “Musk is an absolutist about absolutism, which is the exact opposite of free speech,” Balan told The Times.

Former engineer says Tesla forced her out and then libeled her. Her lawsuit against the company is testing the limits of the arbitration agreements that bind millions of American workers.

Although many companies press employees to sign nondisclosure agreements, Tesla has been a particularly profligate user of them, and of arbitration agreements that prevent those suing the company from making their allegations part of the public record. Tesla requires customers testing its Full Self-Driving technology to sign nondisclosure agreements that say they should “selectively” choose what they post to YouTube because “there are a lot of people that want Tesla to fail.”

Even employees who think they’re playing by the rules may find themselves on the wrong side of Musk’s cone of silence. A member of Tesla’s automated driving team posted videos that showed Tesla’s Full Self-Driving feature working well in some ways and needing improvement in others. Although the videos contained no nonpublic information, he was fired.

Critics outside the company are hardly immune. When Tesla ran into image problems in China, the company responded by asking the Chinese government to censor critical posts by social media users there, Bloomberg reported last year.

Musk’s vendetta against Vernon Unsworth was more personal. When the cave rescue diver told a TV interviewer that Musk was only getting in the way with his plan to rescue Thai children stuck in a flooded cave using a miniature submarine, Musk called the man a “pedo” — or pedophile — on Twitter. (The children were rescued by other means.) Musk hired a private investigator to try to prove his accusation and called the man a “child rapist” in an email to a BuzzFeed reporter.

Unsworth sued for defamation but lost the case at trial, with Musk’s lawyers successfully arguing that a reasonable person would not take the content of his tweets literally.

Musk “is willing to go to great lengths to punish or retaliate against people who speak ill of him,” said Ed Niedermeyer, who struggled to find sources to talk to him, even off the record, for his book on Tesla, “Ludicrous.” Sources who did contact Niedermeyer, the writer said, emphasized that “Elon Musk is not a guy you want to cross.” One source, Niedermeyer said, told him Musk “is like a wild animal when he’s cornered.”

Musk sometimes paints a bull’s-eye on journalists who report negative news about Tesla. He once accused Business Insider reporter Linette Lopez of using inside information to benefit short sellers who were betting against Tesla. Insider trading is a crime sometimes enforced by the SEC.

“From the moment Musk made up lies about me to this very day I have an angry mob of his fans, mostly men, following me around the internet,” Lopez told The Times via email. “They comment about everything from my professional work to my physical appearance. Their attacks don’t have to be true or make sense. Musk’s mob is like an extension of his ego. They join him in whatever fantasy world he wants to live in, they are very aggressive about trying to enforce his reality no matter how warped it is.”

It may be that Musk, if his long-shot pursuit of Twitter comes to fruition, prioritizes unfettered speech and transparency for its users and employees. If so, it will be a departure from the way he has operated to date.

Here’s how Elon Musk’s deal to buy Twitter works and what it could mean for shareholders.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.