Column: The fast-food industry gears up to kill another pro-worker state law

Political PR and advertising firms in California are going to owe Gov. Gavin Newsom a huge favor. That’s because by signing the so-called Fast Recovery Act on Sept. 5, he opened the door to what could be hundreds of millions of dollars in spending by fast-food companies to kill it.

The act — formally the Fast Food Accountability and Standards Recovery Act, or AB 257 — creates an appointed council that could set wage and other workplace conditions for fast-food workers.

The council would be empowered to set a minimum wage as high as $22 an hour in 2023, though there is reason to doubt that wages would hit that ceiling.

Fast-food corporations are looking to buy their way out of a law intended to lift pay for their workers, ensure their stores are safe and healthy and improve the industry for everybody.

— Mary Kay Henry, Service Employees International Union president

(The state minimum wage, currently $15 an hour for employers of 26 workers or more, and $14 for smaller businesses, will rise to $15.50 for all on Jan. 1.)

The restaurant industry has already taken steps to place the law before voters through a ballot measure.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

If the industry can collect about 623,000 valid voter signatures by the first week of December, the referendum would go on the November 2024 ballot and the law would be suspended until then. If the referendum qualifies, voters can expect McDonald’s, Burger King, KFC and their ilk to spend gigantic sums to overturn the law.

We’ve witnessed this spectacle before. It has long been evident that California’s initiative and referendum system has become a playground for rich corporations.

In 2020, some $205 million was spent by gig companies to pass Proposition 22, a measure designed to circumvent AB 5, the state law designating app-based drivers as well as other gig workers as employees of the parent firms, not independent contractors.

The spending by Uber, Lyft and other gig companies set a national record for a ballot measure campaign, swamping the $19 million raised to defeat the measure.

For the proponents of Proposition 22, this was money well spent.

Uber’s revenue came to about $17.5 billion last year and Lyft’s more than $3.2 billion. Neither company has ever recorded a profit, and their paths to black ink would be even more tortuous if they had to pay their drivers a living wage along with benefits such as healthcare, retirement and workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance.

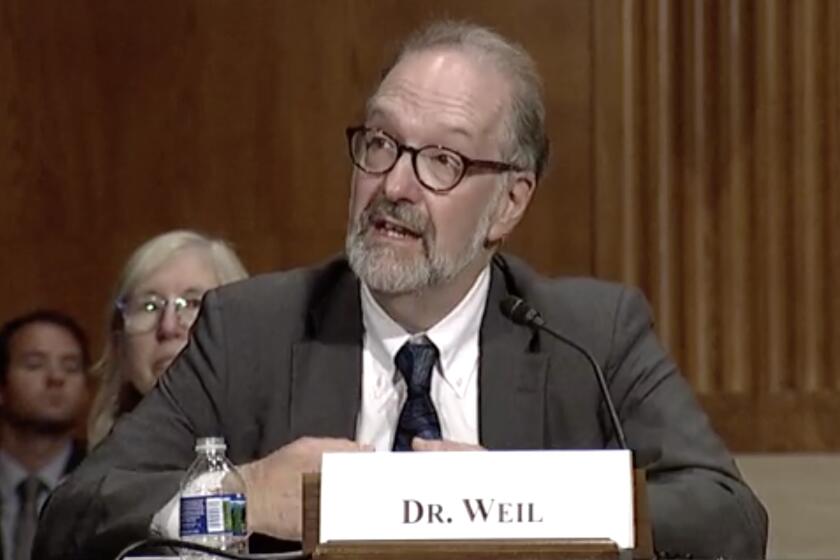

David Weil would have enforced federal labor law leading the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour Division, so Republicans killed his nomination.

(Proposition 22 has been in abeyance since a state judge ruled it unconstitutional in August 2021. Its fate is now before a state appeals court.)

Corporate spending on a ballot fight over the Fast Act might make those gig companies look stingy.

The fast-food franchisers and franchisees have a lot more money than Uber and Lyft. McDonald’s, which says it collected $23 billion at the corporate level in 2021 and its franchisees collected $102 billion, declared a corporate-level profit of $7.5 billion last year. Yum Brands, the owner of the KFC, Taco Bell and Pizza Hut brands, had a corporate profit of $1.58 billion and Restaurant Brands, the Canada-based parent of Burger King, $1.23 billion.

Whatever one might think of the virtues or sins of AB 257, the main question confronting California voters is whether we want to place legislative power in the hands of corporations determined to write laws specifically for the benefit of their executives and shareholders, and to pass them via campaigns of unexampled dishonesty.

The Proposition 22 campaign was a perfect example: The gig companies claimed their alternative to AB 5 would be a boon for their drivers and other front-line workers. As soon as Proposition 22 passed, it became crystal clear that they had lied and the workers were vastly worse off.

It’s a fair bet that the fast-food industry’s plan to overturn the Fast Act at the ballot box will resemble the Proposition 22 campaign.

Service Employees International Union President Mary Kay Henry calls its plan “an act of extraordinary greed and cowardice” in which “fast-food corporations are looking to buy their way out of a law intended to lift pay for their workers, ensure their stores are safe and healthy and improve the industry for everybody.... This isn’t how companies act when they’re proud of their business model.”

The fast-food companies are sure to play on concerns of restaurant operators statewide that the Fast Act will drive costs up not only for big chains but for all dining categories. That’s the fear voiced by Blair Salisbury, the owner of the Pasadena Mexican restaurant El Cholo and a member of the family that operates a half-dozen El Cholo locations across the Southland. It’s not unreasonable.

No surprise: Business leaders’ answer to the port backup is to eviscerate environmental and labor regulations.

“If my cook is making $18 or $19 an hour,” Salisbury told me, “he’ll go work for one of these fast-food chains that has to pay $22 an hour. Everyone’s going to lose their cooks or have to raise their salaries. So it is going to affect the small mom-and-pop restaurants, not just the chains.”

Salisbury recently signed a deal to open a Southern California location for the fledgling chain Daddy’s Chicken Shack and line up franchisees for 19 other regional locations. But he says there’s little interest in launching the chain in California, as opposed to Texas, Florida and Arizona, in part because of laws like AB 257. With inflation taking a bite out of restaurant incomes, a law posing the prospect of higher labor costs “couldn’t have come at a worse time.”

Before examining the specifics of the Fast Act, let’s examine the conditions that gave rise to its enactment. All told, fast-food franchisers employ more than a half-million workers in California, according to the Service Employees International Union, which sponsored AB 257.

As I’ve reported before, the fast-food industry has long been a dark corner of the American workplace.

Much of the problem stems from the franchiser-franchisee relationship, through which “powerful global corporations like McDonald’s ... extract profits” while pushing expenses down to smaller business owners operating franchised locations, Catherine L. Fisk and Amy W. Reavis of UC Berkeley’s law school observed in a 2021 report. “They control the prices and much of the power over quality, hours, and other operations, and the franchisee ... has no way to increase its profits other than cutting labor costs.”

To win drivers’ support for Proposition 22, Uber gave drivers more control over their workdays. Now that the measure has passed, things are changing.

The result, they wrote, is that “operators fail to pay wages to which workers are entitled, deny sick leave, ignore harassment, safety hazards, or disease transmission — they are so squeezed by their franchisors that there is little incentive to comply with the law.”

David Weil, a former Department of Labor official whose nomination to an agency post by President Biden was scuttled earlier this year by the franchise industry and other big business interests, documented in his 2014 book, “The Fissured Workplace,” that unpaid back wages were 50% higher at franchisee locations than at company-owned locations.

The original version of AB 257 would have made the big franchise companies jointly liable for any penalties and fines levied for workplace violations at franchised locations. Labor regulators such as the National Labor Relations Board have been trying to implement such a standard for years, with only mixed success, and fast-food franchisers such as McDonald’s have been fighting it for just as long.

A joint-employer rule would end the big companies’ ability to dodge liability for the workplace violations that are rife in the fast-food industry by hiding behind the franchisees. But it was removed from the bill as one of several changes aimed at making it more palatable for employers, and surely the most significant.

Among other changes made before the measure was passed by the Legislature and signed by Newsom, the fast-food council was reduced to 10 members from 11, and restructured to give employers a larger plurality. The membership was changed from four representatives of employees and two of employers, along with five state regulators from agencies responsible for labor standards and public and occupational health; the final version encompassed four representatives of employees and four of employers, and only two regulators.

The definition of fast-food employers subject to the law was changed from chains with at least 30 locations nationwide to those with 100 or more. Employee scheduling, the topic of persistent worker complaints about unpredictable working hours, was explicitly removed from the council’s jurisdiction, as were benefits such as sick leave and vacation time.

Proposition 22 is a revolutionary step in the influence of tech-based businesses in our daily lives in general and the lives of workers in particular.

Instead of unlimited authority to set the minimum wage for fast-food workers, the final version capped the permissible minimum wage at $22 an hour in 2023, with increases in subsequent years of no more than the rate of inflation and in no case more than 3.5% a year, even if inflation is much higher (as it is currently).

In response, the fast-food industry demonstrated that nothing would please it short of killing the measure in its entirety. Within days of Newsom’s signing of the bill, the International Franchise Assn., the National Restaurant Assn. and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce had launched their campaign under the rubric of the Save Local Restaurants Coalition.

The very name shows that the industry has read the textbooks of the gig firms, bail bond companies and others that have used AstroTurf methods to portray themselves as grass-roots avatars of the common people.

“Restaurants are the heart and soul of the communities they serve,” declared Michelle Korsmo, chief executive of the National Restaurant Assn. (Question: Does anyone really consider their street-corner McDonald’s the “heart and soul” of their community?)

Korsmo also referred to the “unchecked governing council created by the FAST Act”; never mind that the authority of the council is specifically limited by the law, and any recommendations it makes would be subject to review by the Legislature, which would have up to nine months to approve or reject the council’s proposed standards.

How the law would work in practice is unclear. The fast-food council won’t even exist until after a petition signed by 10,000 fast-food workers is submitted to state officials.

Although the panel would have the authority to jump the minimum wage for fast-food workers up to $22 an hour in 2023, that’s probably not a reasonable expectation, since worker advocates will be in the minority on the council and the members in general will be aware that as a full-time wage $22 is more than a third higher than the median income in the state and close to the median starting salary of schoolteachers. In any event, the Legislature might well reject any decision that seems that far out of the mainstream.

If the fast-food companies manage to get their referendum on the 2024 ballot, California voters will get yet another lesson in how big business manipulates the initiative and referendum system for its own ends. The lesson businesses learned from the Proposition 22 campaign, and which fast-food companies are counting on, is that it’s always cheaper to spend money working over the California voting public than doing right by their workers.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.