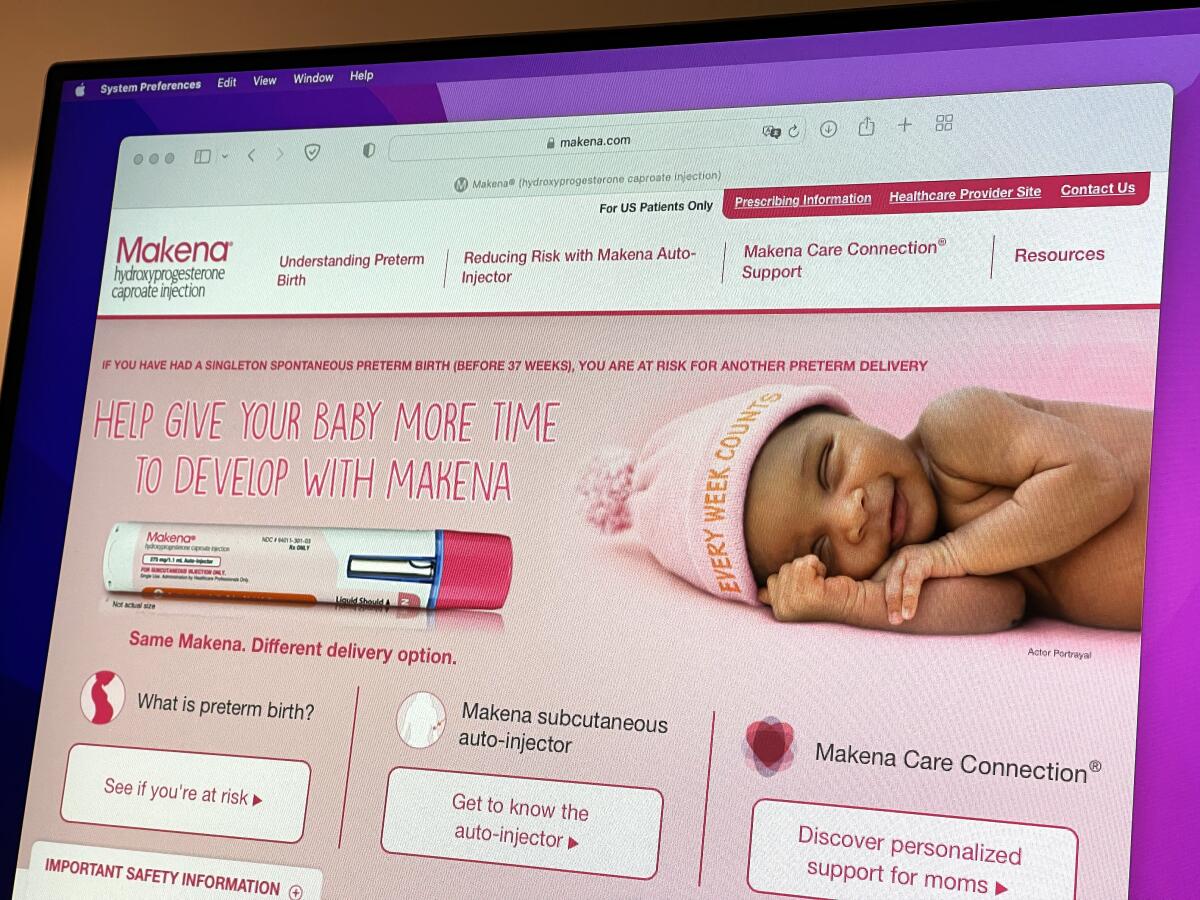

Drug meant to prevent premature births should be removed from market, FDA panel says

A federal advisory panel voted Wednesday to recommend that the only approved drug to prevent premature birth be removed from pharmacy shelves because studies have shown it does not work.

The 14-to-1 vote came more than a decade after the Food and Drug Administration approved the drug, called Makena, on limited evidence, citing the great need for such a treatment.

The Times detailed in a February 2022 investigation how the drug’s maker — private equity-owned Covis Pharma of Luxembourg — and the companies that previously owned the rights to Makena profited by taking a cheap, decades-old medicine with questionable effectiveness and safety and securing FDA authorization for its use.

The FDA called on Covis to pull the drug in 2019 after the results of a large study showed it was ineffective. The company refused.

Under the law, the company was allowed a hearing during which, over the course of three days this week, it argued the medicine should stay available to Black women and others at highest risk of preterm birth. The company said it would attempt to perform a new study to show that those women were helped by the drug.

Before the vote, FDA scientists criticized Covis’ plan. They detailed how it would expose even more women and their children to a drug that had no proven benefits but did have risks, including depression, hypertension and life-threatening blood clots.

The drug Makena doesn’t reduce the risk of preterm birth, a study found, and the FDA recommended it be taken off the market. Its maker has refused.

“In the absence of evidence of effectiveness we are only left with risk,” Peter Stein, director of the FDA’s office of new drugs, told the committee.

Some speakers at the hearing criticized Covis and the previous owners of the drug for aggressively raising its price and then spending heavily to promote it.

Many people also spoke emotionally of the need for treatments to prevent preterm birth. The condition is a leading cause of infant mortality, which is higher in the U.S. than in almost any other developed country in the world.

The 15-member panel included many physicians who care for patients at risk of premature birth. All but one of them voted to remove the drug, saying they were disappointed the drug had not been shown to work.

“I have struggled with this mightily,” Anjali Kaimal, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of South Florida, told the committee. She added that she herself had suffered from a preterm birth that required care of her child in the neonatal intensive care unit.

“To think I would give a very vulnerable population an ineffective treatment doesn’t seem like the right thing to do,” she said.

The panel’s decision is not final. FDA Commissioner Robert Califf and the agency’s chief scientist will consider the vote and testimony and decide in coming months on whether to force Covis to remove the drug.

Makena is a synthetic hormone known as 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate, or simply 17P. The natural hormone progesterone is essential for a pregnancy, but scientists have been unable to determine how supplementing it with a synthetic version might help women take their pregnancies to full term.

Also unknown are the long-term risks of the drug for the woman and her child. A study published in November showed that children of 200 California women who took the synthetic hormone during their pregnancies in the 1950s and ‘60s had a higher risk of some cancers.

Raghav Chari, a Covis executive, told the committee the study was “neither reliable nor relevant.”

The FDA approved Makena in 2011 under its accelerated approval program, which allows medicines to be sold despite limited scientific evidence. At the time, an FDA statistician protested, pointing to flaws in the small government-funded study that appeared to show it helped extend pregnancies.

The agency now says it agrees that the study was flawed and calls the trial’s conclusion “a false positive.”

Under accelerated approval, the company was required to confirm the drug’s benefit in a larger study. That study took eight years. Now three more years have passed since the study’s negative conclusion was announced, showing how an accelerated approval can expose patients to years of ineffective treatments.

Since 2011, more than 350,000 American women have been prescribed Makena.

The FDA determined that Makena, a drug to prevent premature births, doesn’t work. Until the company presents strong evidence otherwise, pull the drug.

With a list price of more than $800 for each weekly shot, the full course of treatment often prescribed during a pregnancy can cost $13,000. Last month, a government report said that Medicaid had spent nearly $700 million on Makena from 2018 to 2021.

In the last two years, Covis has continued to promote the drug, emphasizing its use in Black women.

In 2019, more than 14% of births to Black women were preterm, compared with just over 9% of births to white women.

Covis, which is owned by private equity firm Apollo Global Management, also spent heavily to fund patient and physician groups that supported continuing prescriptions of Makena.

Members from those groups spoke at the hearing, saying they believed removing the drug would hurt Black women and increase racial inequities.

Some of those speakers — including members of HealthyWomen and the National Minority Quality Forum — did not disclose their ties to Covis.

At HealthyWomen, a Covis executive sits on the group’s corporate advisory council. And the National Minority Quality Forum listed Covis as a donor to its summit held in April. A forum spokeswoman said the funding “had nothing to do with” the group’s decisions.

Other speakers told the panel that leaving the ineffective drug on the market would hurt Black women and their children rather than help them.

Elise Erickson, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona’s College of Nursing, told the panel that she believed the ongoing use of Makena amounted to experimentation.

“We cannot subject vulnerable communities to experimentation without consent,” she said, “and doing so in the name of equity is disingenuous at best.”

At the hearing, Covis repeatedly cited continuing support for the drug from two powerful physician societies — the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The Times detailed in its investigation how Covis and AMAG Pharmaceuticals, which owned the drug until late 2019, donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to those two physician groups.

Both groups have published written guidelines that say doctors can continue to prescribe Makena.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.