California fast-food workers form an unusual union in a bid for higher wages, better working conditions

- Share via

Mysheka Ronquillo works as a cashier and cook at a Carl’s Jr. in Long Beach, earning $16 an hour. She’s looking forward to a raise to $20 an hour in April, thanks to a new law signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom last fall.

The higher wages will help her pay for school for her 19-year-old daughter, but keeping up with her bills still will be hard because of an unstable schedule that has her working 30 hours some weeks and 24 hours other weeks, she said.

“Gas isn’t going down, rent isn’t going down,” said Ronquillo, 41, who joined an estimated 350 other fast-food workers at a rally at a Watts community center to inaugurate the state’s newest labor organization, the California Fast Food Workers Union.

The union is a unique effort that will pave the way for more than half a million workers at fast-food chains across the state to bargain as a single sector — and could chart a course for other industries across the United States.

Backed by the powerful Service Employees International Union, the California Fast Food Workers Union is the culmination of years of employee walkouts over issues including the handling of sexual harassment claims, wage theft, safety and pay, such as the Fight for $15 movement to increase the minimum wage, organized by SEIU in 2012.

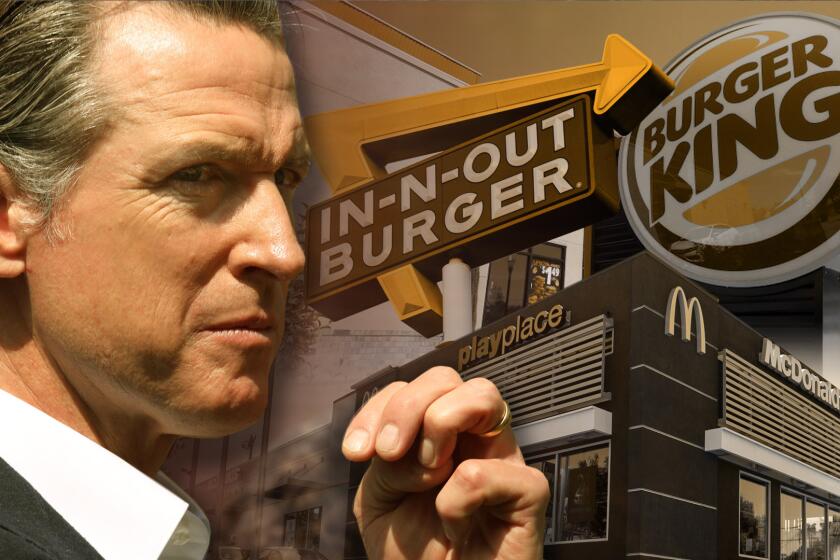

The law, hammered out with the help of Gov. Gavin Newsom, increases wages for workers and allows business and unions to avoid a costly ballot fight over wages.

“Led by Black and Latino cooks and cashiers, the California Fast Food Workers Union is setting a shining example of what is possible,” SEIU International President Mary Kay Henry said in announcing the union Friday.

The union outlined three priorities: annual wage increases, just-cause protections to prevent employers from arbitrarily firing workers, and ensuring workers have predictable and sustainable schedules, without major changes to their hours.

The new organization isn’t a traditional union, instead using the model of a so-called minority union that allows workers to avoid the arduous process of organizing restaurant by restaurant through a formal election process certified by the National Labor Relations Board.

“This is a novel approach to organizing workers who have previously not been in unions,” said Kent Wong, director of the UCLA Labor Center.

Such organizing picked up steam during the pandemic, when essential workers were “on the one hand celebrated as essential workers … but in reality making poverty wages and not being truly respected on the job,” Wong said.

Fast-food workers are walking off the job in support of a California bill that would establish a council to negotiate standards on wages, hours and other work conditions.

Union pushes at Starbucks, Amazon and Trader Joe’s and organizing among Uber and Lyft drivers are just a few examples, he said. All of the workplace-by-workplace organizing efforts have been slowed by corporate opposition.

The fast-food union shows the evolution of these campaigns and could serve as a model for nonunion workers in other industries besides fast food, he said.

Traditional union organizing at fast-food restaurants has been exceedingly difficult because of the industry’s fractured nature. Often, restaurants are not owned by a familiar brand’s parent corporation but rather operated as franchises.

And even when one company is the owner, such as the case with Starbucks, workers at individual locations frequently must unionize and bargain with the corporation separately.

The new fast-food worker union won’t have the legal strength to compel companies that employ their members to sit down and bargain because it is not certified by the NLRB.

Fast-food companies, under a complex peace accord with labor unions, will pull a referendum off the California ballot that sought to reverse AB 257.

But the new union aims to build on Assembly Bill 1228, or the Fast Recovery Act, signed by Newsom in the fall. It established a $20-an-hour minimum wage starting in April and created a council to set standards for wages and workplace conditions at fast-food chains with 60 or more locations.

The Fast Recovery Act provides annual wage increases of up to 3.5% during the first three-year cycle of the Fast Food Council. The California Fast Food Workers Union will be a vehicle for workers to set the agenda for their participation in the council, which will be made up of workers, labor advocates, corporate representatives and franchisees.

The council has limited purview; for example it does not have the authority to regulate paid sick leave, vacation or predictable scheduling at franchisees.

The California Fast Food Workers Union will lobby for local ordinances to fill in the gaps where the new statewide council may not have authority, SEIU leaders said. Workers who join the union will pay $20 in monthly membership dues, SEIU spokesperson Isabel Urbano said.

Henry said in an interview that she believes the new union’s plan to push local ordinances and lobby the fast-food council are steps toward making predictable scheduling and other issues statewide standards.

“This is a vehicle to make things much bigger for many more workers all at once,” she said.

City Councilmembers Hugo-Soto Martinez in Los Angeles and Peter Ortiz in San Jose last year began drafting ordinances to strengthen protections for fast-food workers. SEIU said Friday that the new union will call on officials to commit to passing those Fast Food Fair Work ordinances outlining paid time off provisions, predictive scheduling tools and mandatory “know your rights” training for workers.

Henry, the SEIU president, said that she sees the creation of the fast-food union as a major turning point. Four years after the union started its Fight for $15 campaign in 2012, many cities as well as the states of California and New York had made it law.

“I remember people ridiculing and scoffing at the demand for $15,” she said. “When there’s a spark and something more becomes possible, then more people want to join it.

“More change is going to help people think, ‘This wasn’t a crazy idea after all.’”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.