Gay shopkeeper stands his ground in a Central Valley town, carving out space for others

Gil Ramirez immigrated to the U.S. more than 20 years ago to escape persecution he experienced in Mexico as a gay man. Now he choreographs and teaches dances for quinceañeras in Mendota, Calif., a small town 35 miles outside of Fresno. “I think Mendota needed someone like me,” he said.

MENDOTA, Calif. — Gil Ramirez — chin up, chest out and wearing a big, red flower pinned to his black-and-white-striped sweater — crossed the main street.

Three men in a car flung Spanish slurs for “gay man.”

“Thank you, but you’re not my type,” Ramirez yelled back with a shrug.

Another group of men standing outside the pool hall (Mendota’s version of a Greek chorus, always offering commentary on events around them) laughed. Ramirez had won that round.

He usually does.

“Ask anyone in Mendota, and they know who is Gildardo Ramirez,” he said.

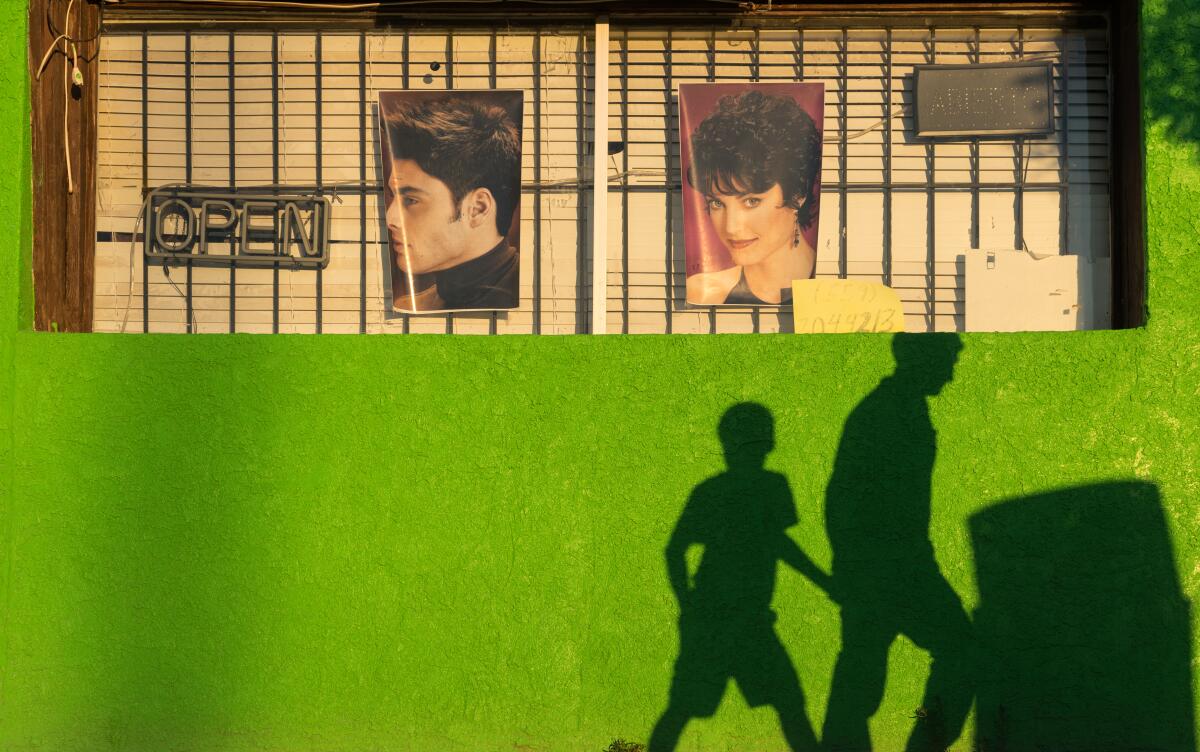

In a small town, far from the subcultures of a big city, it can be hard to be gay or any kind of different. But a small town is also where one person can be so much a part of the fabric of life that he sets his own rules on acceptance and visibility.

In Fresno — at 35 miles away it’s the nearest urban center — Andy Garcia tears up at the thought of Ramirez and others like him.

“We owe them,” said the 25-year-old LGBTQ activist, who grew up in the Fresno County town of Clovis. “All along in these little farm towns, there was always one or two people who stood their ground and said: ‘This is who I am and I’m part of this place.’ Where would we be without them?”

In Mendota, Ramirez choreographs and teaches dances for quinceañeras, swaths halls in tulle for weddings and anniversary parties, acts as an emcee and deejay and works at the flower shop — a place central to the celebrations and joyful moments in an agricultural town of 11,000 where life is often harsh.

Families here fear separation because of immigration status. Raids in Central Valley fields and packing houses last year had parents lined up at the notário office, naming emergency guardians for their children in case they got caught in a sweep and didn’t return home from work one day. It’s a fear that hasn’t eased.

Standing outside Los Amadores Flowers & Gifts, you can see the spots where four slayings have occurred in recent years — at least two of them connected to the infamous MS-13 street gang.

The shop used to sell religious iconography, so there is a life-sized Jesus statue out front, red dabs of paint on the hands and feet. It stands next to a gumball machine and a shaved ice cart.

The “Happy Valentines Day” banner in the window is especially dated in a place where life is ruled by the seasons. February is when there is only pruning work until the asparagus harvest. Now it’s just past melon season. (The city slogan is Cantaloupe Center of the World.)

A fifth-grader from Honduras bicycled up to the gumballs, quarter in hand. Last summer he and his father were separated and jailed in Texas, after they walked through Mexico and tried to cross the border by swimming the Rio Grande. Now his father, still wearing the electronic ankle bracelet they put on him before his release, was at work in the fields.

Inside the shop there was a gentler side of Mendota. Someone ordered balloons for a niece who just had a baby. Another customer wanted a birthday rose for a maybe-more-than-a-friend at the almond-packing plant.

Ramirez’s phone rang — another quinceañera dance lesson request. His ring tone is a Donna Summers song.

Matthew Vega-Tamayo, 18, and his best buddy tumbled in with the energy of puppies. The friend had set him up with a “really pretty girl” from neighboring Firebaugh who wanted a date for a formal event. Vega-Tamayo decided white flowers with silver ribbons would go well with her dress and the navy suit he plans to wear.

He started working the fields when he was 12 (“When they ask if you’re 18, you just say yes.”) But now he also has a job at the Taco Bell in town, and for the first time has money for more than necessities.

He’s got plans. He’s graduated high school. He is going to go into real estate. That’s the reason for the suit.

“Why rent a tux when I can buy a nice suit and it will look good for prom and for when I’m a mogul,” he said with a wide grin. “I love my life. Don’t get me wrong. It’s been rough. But I know so many things because of it.”

One thing he knows is how to dance.

Ramirez taught him when Vega-Tamayo was a reluctant 16-year-old roped into a quinceañera, the elaborate 15th birthday celebration that for a girl marks adulthood in Latino culture.

“It was either dance or watch my girlfriend at the time dance with another guy. What would you do?” Vega-Tamayo asked.

He showed no natural ability. But Ramirez kidded Vega-Tamayo until he loosened up and got the steps.

The dance classes aren’t money-makers. Ramirez charges $40 for several weeks of practices.

“I do it because it makes me feel alive,” Ramirez said.

In the winter he holds lessons in an empty watermelon warehouse, but come spring they move to a park in the nearby town of Firebaugh.

On a recent evening, Jisel Cabrera and 14 of her closest friends practiced for the party she said she had been imagining her whole life.

Ramirez muttered and sighed as the teens, with their baby faces and coltish bodies, bumbled a run-through. He coaxed them until they made it through steps that ended with Jisel being lifted high in the air by her escorts. Just then the setting sun gave everything a rosy glow.

The next week, Ramirez’s older sister died unexpectedly. He put a closed sign on the flower shop and canceled all dance practices.

He was inside surrounded by buckets of yellow roses for her Mass.

“She loved yellow. Like me,” he said.

When the shop reopened a week later, Ramirez’s hair was electric blue. He said he cried for three days straight, then dyed his hair because that makes him feel different inside.

He came from Mexico at 22, the son of a middle-class shopkeeper. He left his supportive family because he felt under constant threat of violence by men who called him the same things as those men in the car.

He’s in his 50s, a fact that he seems to expect be met by exclamations of disbelief. His decorating style — ’80s excess — is out of favor with younger brides who scroll through Pinterest photos of farm-chic, but it’s still beloved by the customers who believe more is more.

Fernando Valenzuela, 33, who helps run the pool hall, said he has to smile whenever Ramirez walks by in that day’s carefully coordinated outfit.

“No one else dresses like that here. He carries himself with confidence. I always shake my head a little and think, ‘That dude is brave.’”

Miss Jenny, who’s in charge at the thrift shop across the street from Los Amadores Flowers, also keeps an eye on Ramirez as he chats with people around the downtown square. He isn’t a friend.

“I don’t make friends,” she said. “But I watch, and the florist is very popular.”

Miss Jenny doesn’t want to draw attention to the fact that her driver’s license says she’s male. She came to Mendota a year ago from Mexico, where she says she was beaten as a youngster for having feminine traits. She bought hormones at a swap meet and gave herself shots, hoping that if she looked different the violence would stop. It didn’t, and she came here to run her brother’s store.

Most everyone in town comes through the one-stop shop to buy a cell phone or bed or soccer jersey. Miss Jenny has had about 20 customers she believed to be LGBTQ. But none as open as Ramirez.

“Maybe he makes more space in this place for others to be OK,” she said.

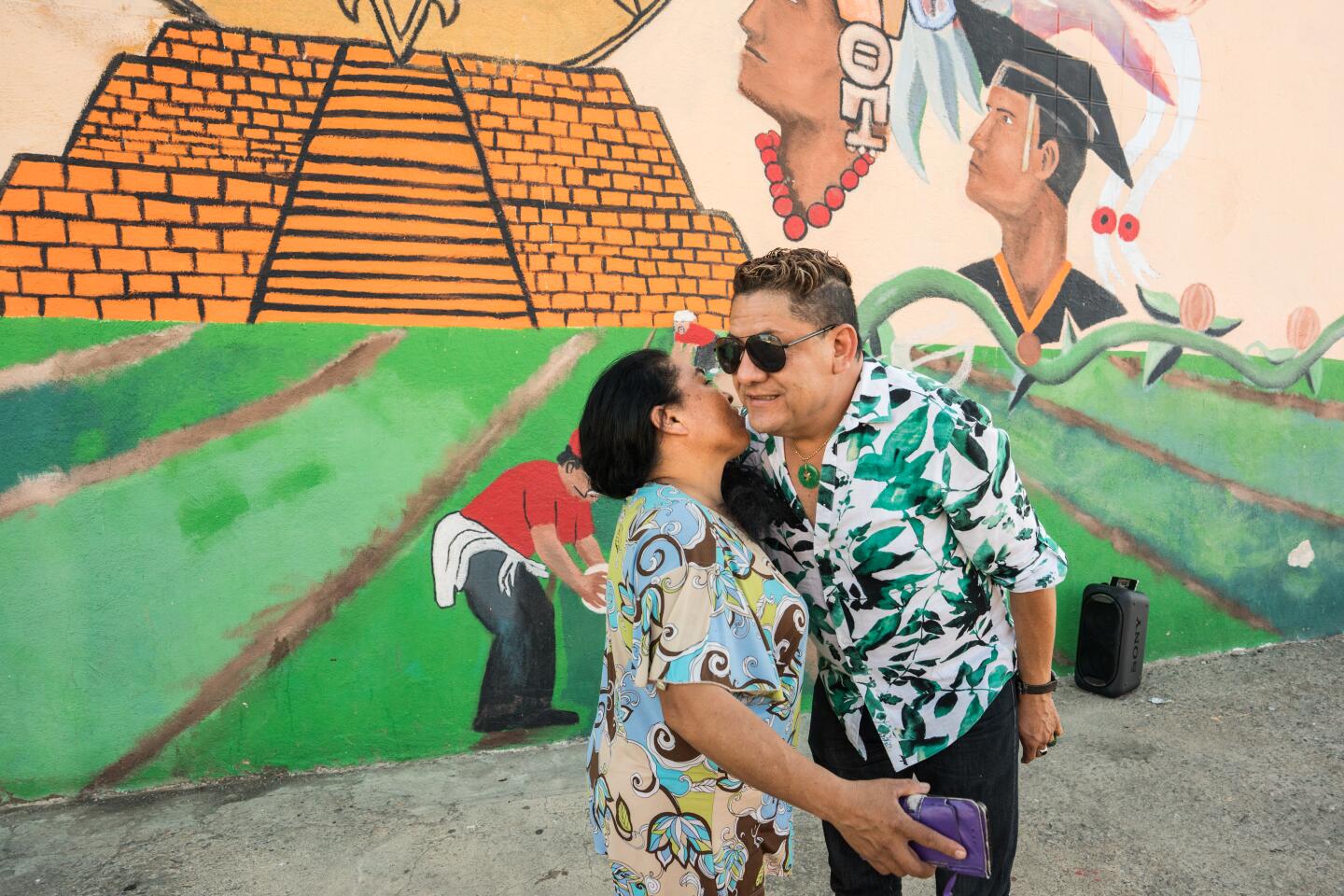

At one of the top quinceañeras this season, at the event hall owned by the family who owns the tractor tire shop, Ramirez, sporting a plaid suit, was in his element — “the belle of the ball,” he said.

A group of the fathers stood drinking beer and shooting disgusted looks his direction.

But this wasn’t a street corner, this was Ramirez’s domain.

“Excuse me, I can’t hear you,” he said to the men. “Talk louder.”

They went silent.

“Leave that stuff in your old country,” Ramirez told them. “This is California. There’s freedom here.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.