Column: What if I were homeless? An immersion course in empathy in San Francisco’s Tenderloin

Imagine that you are homeless, that you have no money, that you have spent the night wary and watchful, huddled on hard city sidewalk. Imagine that you are exhausted. Feel how your hunger gnaws. Join the line for a free lunch that stretches down the block.

Flip your perspective. Adjust the angle of your view. Open yourself up to the pain and suffering that you cannot avoid if you look. Try it on for a moment. Bear its weight. Hold it, however briefly, as your own.

This is what a small group made up mostly of prosecutors and police officers was challenged to do this week in an extraordinary immersion course designed to expand empathy. I was invited to witness them doing it. And as I joined them in experiencing life on the streets of San Francisco’s Tenderloin, I did it too, because how could I not?

I saw people competing with pigeons for the stray scraps of food in the curbside trash. I saw a block roped off with yellow police tape, blood staining the street. I saw a man’s cracked and gnarled feet protected only by duct tape, a woman with a face so gaunt it appeared to be caving in. I saw luxury apartment buildings rising up and casting their shadows on people lying on the sidewalks below. I saw a cardboard home made from a box that once held a couch.

I saw the same sorts of things there that I often see here — but with experts by my side to help me look at them with fresh eyes.

This week, officials toured our own skid row on behalf of President Trump, who seems now to have an interest in California’s homeless crisis and has suggested that such sights “ruin our cities” and that he might need to “get that whole thing cleaned up.” I think it’s safe to say that the tours I joined had a different aim: to fully take in and absorb a reality that can’t just be swept away — and to see in it fellow human beings in extremity whom we should all try to help, not just trash and waste and blight.

A lot of us who live our lives in comfort, with doors that lock, roofs over our heads, mattresses to sleep on, refrigerators full of food, prefer not to rest our gaze on the many among us who do not have. We want to blink their tent encampments away. We want those in power to remove them. And often we are quick to judge the people on our streets — for the way they may look, for the way they may smell, for the way some of them twitch and flail and talk to no one we can see, for the way some seek some sliver of solace in pipes and needles and booze.

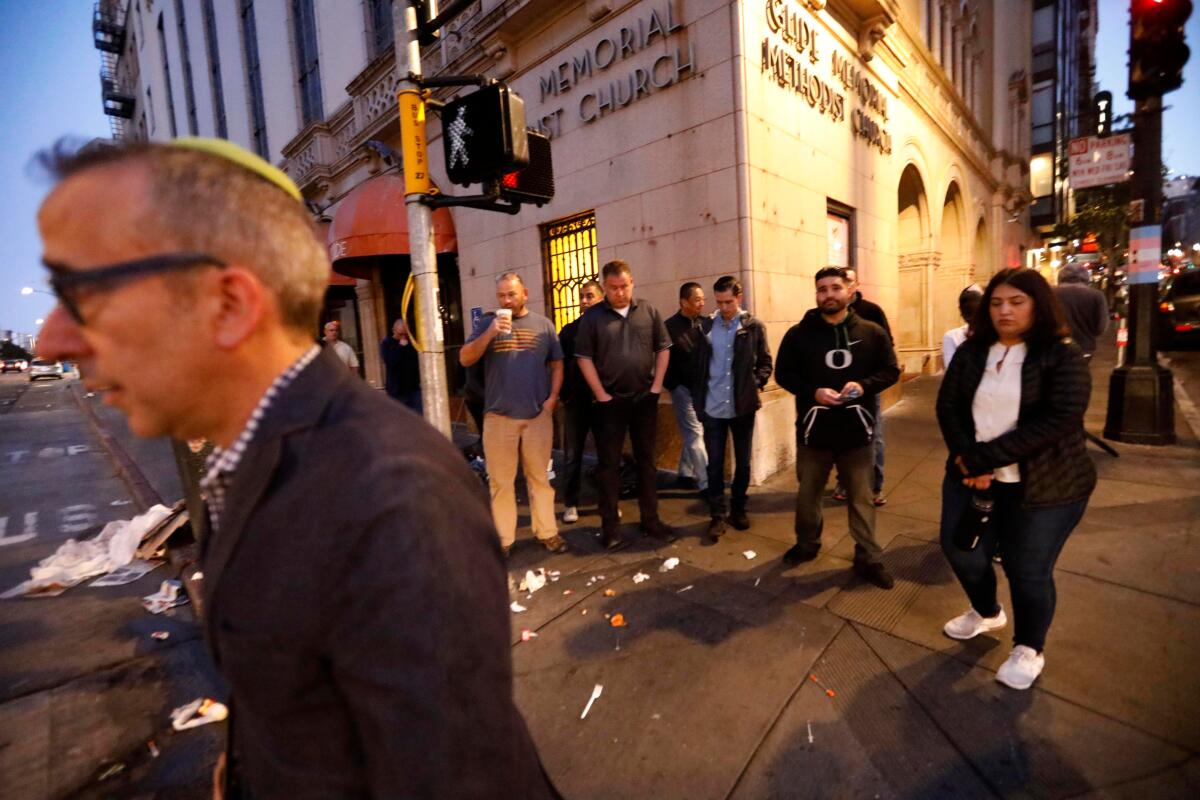

The immersion course is run from the wholly different perspective of the Rev. Cecil Williams’ famously liberal and all-embracing Glide Memorial Church, a place with a storied half-century history of fighting for San Francisco’s LGBTQ people, poor people, disenfranchised.

Glide’s central goals include providing unconditional love and being “radically inclusive,” welcoming, valuing and showing respect for all. Its front door is unlocked. It serves three meals a day, 364 days a year. It runs a broad range of programs to help the most needy and has a center for social justice that wants to foment the kind of huge structural and societal changes that probably will be required to turn this crisis around.

In the course, called “An Officer and a Mensch,” that center’s staff rabbi, Michael Lezak serves as the guide. He is slim and soft spoken and thoughtful. He wears a lime-green yarmulke. He solicits reactions and listens actively and offers ideas for further reflection.

One minute he might be explaining the Jewish tenet of tzedakah, or righteous giving — telling the story of a mentor who always carried two purses, one full of things to give to others. The next he might share one of his own moments of revelation in making a transition from a rabbi in wealthy Marin County to working in a place of such unrelenting need.

His is a generosity unbound by rules, regulations and codes. Not so for those he is talking to in law enforcement and criminal justice. But, he keeps reminding them, don’t we all want to do the same thing, to help?

Maybe the two worlds can overlap more?

“Put on your Glide goggles and try to think: How is Glide walking through the world and how might that change how I walk through the world — whatever I do, as a human being, as a professional,” he tells them.

The idea for this mind-shifting course, which now has been given half a dozen times, comes from Matt Carmichael, chief of the University of Oregon Police Department (who formerly headed the Police Department at UC Davis) and Jeff Reisig, the Yolo County district attorney. They wanted to jolt those in their lines of work into thinking more generously and creatively about how to help the most vulnerable. And they hope it is an idea that will spread.

The first evening, Del Seymour, who is known as the mayor of the Tenderloin, leads a tour of the neighborhood, where he was homeless and an addict and a drug dealer for 18 years. He now is co-chair of the city’s Local Homeless Coordinating Board and the founder of a nonprofit that prepares the underprivileged for good jobs, especially in tech companies.

He tells the story of a man he found living in his car, who once had been a successful Beverly Hills psychiatrist. The man said his name was Joe. Seymour would only call him Doctor Joe — because that’s who he was, that’s who he needed to recover his way back to being.

Treating people with dignity matters, Seymour says: “We don’t have a closet full of dignity or self-esteem that we can give out to folks. They already got it. They just don’t know where it is. So we help them navigate and find out what pocket that dignity’s in.”

On the streets of the Tenderloin, he can’t go more than a few steps without warmly greeting a friend.

And in the three days the group spends learning from Seymour and others, they will hear story after story about how such small gestures have saved lives that so easily could have been callously written off.

About 40% of Glide’s staff comes from the Tenderloin community. Others employed there have their own stories of adversity. One woman who now works both with battered women and their batterers says she was abused and also has been homeless — living in a storage shed, showering at the gym.

Another Glide staff member shows them the track scars on his arms and tells them about being so deeply addicted that he never contemplated treatment — until one day he heard the music of a Glide Sunday service and walked in and was the opposite of shunned.

A homeless Glide client tells me of the looks of disgust he gets from people who “pedestal themselves” and insist on believing in their own invulnerability. A former drug addict who now participates in a pilot program to try to keep addicts out of the legal system recasts my own fears of some of the denizens of my Hollywood neighborhood when he describes his own fear as a young man, on the streets alone, afraid to shut his eyes and so living on speed.

One morning, at 6:30 a.m., everyone gathers on a Tenderloin corner. The rabbi has an assignment for the group, which includes prosecutors, investigators and a victim advocate from the district attorney’s offices in Santa Clara and Yolo counties, as well as members of the University of Oregon police based in Eugene, and two young San Francisco police officers.

The rabbi tells each person in the group to spend 20 minutes “meandering” down the street, trying to be “as present as possible.” “I want you to notice beauty, “ he tells them — but also “spend maybe a third or half of your time looking at the pain.”

He points out the Four Seasons Hotel a few blocks away, where some rooms cost more than $700. Where they are standing, he says, you can at the same time see that temple of privilege and a desperate person rifling through trash.

He asks that they hold both realities in their heads “and maybe let that break you a little.”

Then he tells them that later they’ll be helping to serve all those who come to eat breakfast in Glide’s basement — doing whatever is asked, filling trays, clearing tables.

“I’m going to hereby deem you employees of their Four Seasons,” he says. “Think about if you had stayed the night there last night, how people would dote on you and take world-class care of you and ask you how you are. You’re going to deliver that service in the basement here. Fair?”

During breakfast, I lean against a pillar and watch as hundreds of people move through the line, get warmly greeted and served oatmeal, sandwiches, eggs and bacon, pastries and shiny red apples. I watch as the supervisor scans who’ll be coming in next and quietly asks for apples to be left off the trays of the toothless.

I watch a top prosecutor line up trays and an investigator scoop oatmeal. I see a lot of young men, so ragged and dirty as to look almost feral. One covers his face with one arm as he eats and drinks, shielding himself from view. A few catch my eye and see my smile and give me looks of such startling softness that all I can think is this is somebody’s lost son.

And even though I am doing nothing but watching and greeting those who come my way, people keep walking up to me and thanking me profusely.

At lunchtime, when the group is told to join the line outside the building for food, I do so with everyone else so as not to mess up the experience by watching. Outside the building, we stand out — crisp shirts, clean clothes, no evidence of hardship. Plenty of working people get their meals at Glide. Some spend all their money on rent and have nothing left for food. But still I expect someone in the line to spot us as suspect and look at us askance. No one does.

In fact, the opposite happens.

I am the only woman at a table of men. There are four of them, two young, two old, all bent over their food, eating with the utmost weariness. They make no eye contact except for when one of the older men points to a younger man’s uneaten chicken salad — which he wants and which the younger man lets him take.

I am watching this wordless exchange when an older woman, maybe in her 60s or 70s, comes up to me holding out her tray, swept clean but for her own chicken salad. Do I want it, she asks me. I should eat it, she says. It is all I can do to hold back my tears.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.