Seeing those opt-out messages about your personal information on websites? Thank California’s new privacy law

“Do not sell my information” links popped up on websites New Year’s Day as companies scrambled to comply with California’s sweeping new consumer privacy protection law, which allows customers to instruct businesses to not sell their personal information.

The announcements were required as part of the California Consumer Privacy Act, which went into effect Wednesday, just one part of the most powerful consumer privacy protection law of its kind in the United States. Advocates believe the law, passed by the state Legislature in 2018, could be used as a model in other states or nationally.

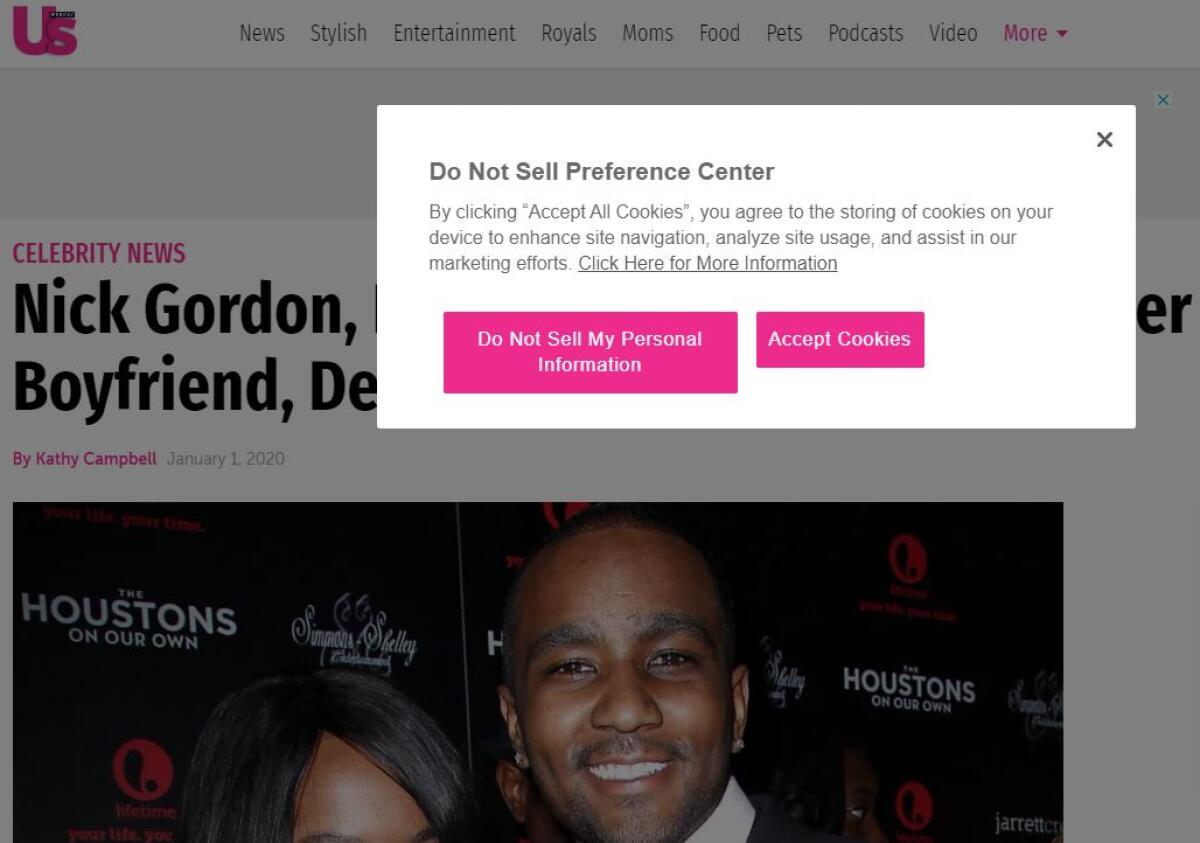

Its most notable immediate impact, the “Do not sell my info” links, began showing up at the bottom of websites for businesses such as Home Depot and Ralphs or as pop-ups on publications like Us Weekly.

The law, Assembly Bill 375, authored by Assemblyman Ed Chau (D-Arcadia), says a clear and conspicuous link on the business’ homepage must enable a consumer to opt out of the sale of the consumer’s personal information.

On one website explaining the options, the site says, “You may exercise your right to opt out of the sale of personal information by using this toggle switch. If you opt out we will not be able to offer you personalised ads and will not hand over your personal information to any third parties.”

Here’s what the law is intended to allow you to do, according to Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra’s office:

You have the right to tell a business: Don’t sell my personal information.

Customers are able to tell a business that sells personal information to stop selling it.

You have the right to delete personal information held by a business.

Businesses are required to create procedures to respond to requests from customers to delete their information.

You have the right to know what personal information is being collected or sold.

Companies are required to provide notice before or as they collect data.

You have the right to not get worse service or a higher price if you exercise a privacy right.

Consumers are not to be discriminated against by the business when they exercise a privacy right.

Californians have newfound power over their online information in 2020. Here’s how to exercise those new rights.

How the law will be enforced is still up in the air. As The Times’ Sam Dean writes, a set of regulations accompanying the law from the attorney general’s office is still in draft form, and a final version won’t likely be ready for a while.

Here are some questions and answers related to the new law, based off of previous Times stories:

Why was the law created?

The idea began with a San Francisco real estate developer who had a chance cocktail party conversation with a tech engineer, who said, “‘If people just knew how much we knew about them, they’d be really worried,’” Alastair Mactaggart recalled of that chat with the engineer to The Times’ John Myers.

“These big companies know so much about you,” he told The Times’ George Skelton.

Mactaggart was prepared to take his proposed privacy law to California voters, and spent $3 million to gather signatures for the initiative. But to avert a showdown at the polls, state lawmakers acted and passed their own law, and Mactaggart shelved the ballot initiative.

What do opponents of the law say?

Opponents of the initiative bemoaned the bill, but said it was slightly preferable to the proposal slated for the ballot, in part because it narrowed the circumstances under which consumers could sue companies, The Times’ Melanie Mason wrote.

What do tech and communications firms say about the idea of a federal privacy law?

Some major tech and communications firms have said they support federal laws that would safeguard user privacy if those laws aren’t as stringent as rules recently introduced in Europe and California.

As The Times’ David Pierson wrote in 2018, privacy advocates want Congress to take a cue from the California Consumer Privacy Act and the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation. Those laws are designed to give consumers far more control over their data, but companies have opposed them because of compliance costs, expensive penalties for violations and the restrictions on collecting data.

Is the fight over privacy laws over in California?

No. As The Times’ John Myers wrote in October, Mactaggart wants to press ahead and do more, proposing a 2020 statewide ballot measure that would give Californians more control over the collection of their health and financial data and there would be stiff penalties for companies that wrongly share and sell data about children.

A central component of the ballot measure is additional consumer control over what Mactaggart calls “sensitive personal information,” including data on a person’s race, health, Social Security number and recent locations using GPS technology. If enacted by voters, the law would grant consumers the right to prevent that kind of data from being sold and/or used for advertising purposes.

He is also proposing stricter rules regarding data collection from children, citing recent concerns about YouTube’s practices.

What companies must follow this law?

A business is subject to the law if any one of the following is true:

- It has gross annual revenue in excess of $25 million

- It buys, receives or sells the personal information of 50,000 or more consumers, households or devices

- It derives 50% or more of annual revenue from selling consumers’ personal information

As The Times’ Michael Hiltzik wrote, that includes a wide swath of the internet, including web giants like Google, news outlets including The Times, e-commerce sites and more.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.