Justice Ming Chin to retire from California Supreme Court, giving Newsom his first appointment

SAN FRANCISCO — California Supreme Court Justice Ming W. Chin said Wednesday that he will step down Aug. 31, giving Gov. Gavin Newsom an early opportunity to put his stamp on the state’s highest court.

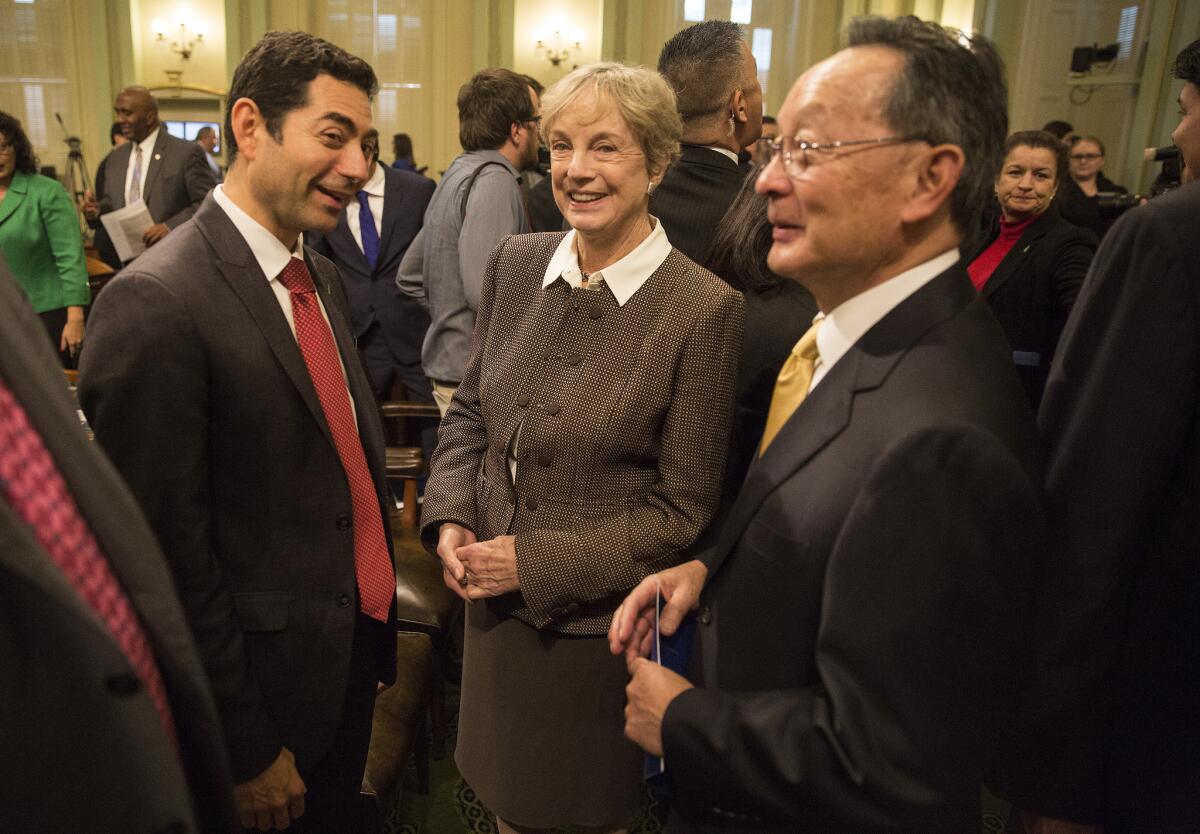

Chin, 77, joined the court nearly 25 years ago, becoming its first Chinese American justice. At the start, the appointee of then-Gov. Pete Wilson, a Republican, was considered a moderate voice on what was then a conservative court.

Now the seven-member court has a Democratic majority for the first time in decades, and Chin is considered its most conservative member.

Chin will turn 78 on the day of his retirement and announced it Wednesday to give Newsom plenty of time to vet candidates for his first appointment to the state high court. The next appointee will give the court five of seven justices chosen by Democrats.

Newsom said he was surprised to learn about Chin’s retirement and joked that some may “shudder” when they hear he’ll be filling the seat. He called the responsibility “sacrosanct.”

“I don’t do this from an ideological lens,” Newsom told reporters at a news conference on homelessness in Fresno on Wednesday afternoon. “We have a very, very deliberative process that’s also not political, and we vet people.”

Noting that his father was an appellate judge, Newsom said he would look at candidates’ qualifications, where they live and whether they represent the diversity of the state.

Still, Newsom’s appointee is expected to be more liberal than Chin and will likely tilt the court leftward.

The moderately conservative Chin has been supportive of the death penalty and inclined to rule for prosecutors. For years he was considered the court’s most expert justice on forensic evidence.

He dissented with two other justices from the court’s historic 2008 decision to overturn California’s ban on same-sex marriage, arguing it was up to the electorate or the Legislature to decide the question.

Among the possible candidates for Chin’s seat is Court of Appeal Justice Therese Stewart, one of the legal leaders in the fight for same-sex marriage. A former chief deputy San Francisco city attorney, she defended then-Mayor Newsom’s decision in 2004 to defy the marriage ban. Former Chief Justice Ronald M. George, the author of the decision against the ban, later cited her legal acumen in the case.

Voters soon overturned the marriage decision by passing Proposition 8, which eventually was struck down, and former Gov. Jerry Brown put Stewart on a San Francisco-based court of appeal in 2014. If elevated, Stewart would become the court’s first openly gay justice.

Chin also was a pioneer because of his ethnicity. Through much of his career he has been active in groups designed to overcome ethnic prejudice, and has cited as his heroes the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whom Chin once met, and Indian pacifist leader Mohandas K. Gandhi, the latter because of his influence in Asia.

In applying for a judgeship in 1989, Chin wrote: “I am very proud to have opened some doors for others of my ancestry, but I will be most proud when it is no longer unusual for minorities to hold the kinds of positions in which I have had the privilege to serve.”

The son of uneducated Chinese immigrants and the youngest of eight children, Chin grew up working seven days a week on his family’s potato farm near Klamath Falls, Ore. As a boy, he learned to operate a tractor, Jeep, hay baler and combine.

During an interview, Chin recalled that he and his family sometimes were denied rooms at motels because of their race.

“We would seek accommodations, driving back and forth around Klamath Falls, and drive into motels, vacancy signs blazing in the window,” he remembered. “But there would be no room for us in that establishment.”

When he was about 10, he said, he suggested to his father that it would be good to live in Klamath Falls.

“Oh, no,” he said his father replied. “They don’t let Chinese live there.”

“Why not?” the boy asked.

“Maybe you can do something about it some day,” he said his dad told him.

Chin later served in the Vietnam War and earned a Bronze Star.

He was educated at Jesuit schools, from high school through college, receiving both his undergraduate and law degrees from the University of San Francisco.

He began his legal career as a prosecutor in Alameda County but left after only a few years for private practice. Then-Gov. George Deukmejian appointed him to the Alameda Country trial bench and later elevated him to the San Francisco-based Court of Appeal.

At a 1996 news conference on his appointment to the state’s top court, Chin said his only sorrow was that his parents did not live to see him attain the honor.

“Only in America could the son of a Chinese immigrant farmer rise to sit on this state’s highest court,” he said in a quivering voice as he accepted the appointment.

The new justice was immediately thrust into controversy after saying in response to reporters’ questions that he supported abortion rights.

Shortly after he was confirmed, he joined a four-judge majority to overturn a state law requiring minors to obtain parents’ consent for abortions. Anti-abortion activists targeted him, and he had to assemble a campaign for his first retention election. Despite the opposition, he was easily retained.

Among Chin’s many court decisions was a 1996 ruling that allowed battered woman syndrome to be used as part of a murder suspect’s self-defense claim, a decision that he singled out Wednesday as one of his favorites.

“My first assignment as a trial judge was in family law, and I taught family law at USF,” he said. “So these domestic violence situations are, I think, an important part of what judges do. We have to handle them very carefully.”

Another decision he cited with pride was Sargon Enterprises Inc. vs. USC. Chin, in a 2012 unanimous decision, wrote that trial judges had a duty to exclude speculative expert testimony.

He also authored a 2001 decision that said gun manufacturers weren’t liable for negligence even if their weapons were used in a crime.

He said he has no regrets about any of the 350 majority decisions he wrote for the court or his 100 concurrences and dissents.

“I haven’t been one to second guess,” he said.

He noted that a Court of Appeal justice once told him his rulings were known for their clarity and courage.

“If that is what is written about me in 50 years, I would be happy,” he said.

Chin has been active in helping Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye and other judicial leaders run the branch, and his decision to retire will likely leave a void on the administrative side of California’s court system.

Cantil-Sakauye called his loss to the courts “incalculable” and praised him for helping the court system embrace technology to expand public access.

“He has been a valuable mentor who took me under his wing when I first became chief justice,” said Cantil-Sakauye, who was appointed by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. “Before he joined the bench, he spent years performing at the very highest levels of the legal profession and is an accomplished teacher and lecturer.”

Chin and his wife, Carol, have been married for 48 years and have two children — Jennifer Chin, who is senior counsel for the University of California’s Office of the President, and Jason Chin, an Alameda County Superior Court judge — and five grandchildren.

Times staff writer Phil Willon contributed to this report from Fresno.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.