15 deaths in the airline industry in 9 days linked to coronavirus. Why are planes still flying?

- Share via

Somehow, word got around among retired New York City firefighters about a perfect second-career job: a local company, with lots of travel perks. One by one, they became flight attendants at JetBlue.

Ralph Gismondi was among the first of an estimated 30 or so former firefighters who joined the airline. He retired as a fire captain after several decades that included a stint at ground zero on 9/11. He began working as a flight attendant for JetBlue in 2003 and saw each trip as a chance to fine-tune his comedy routine over the public address system. On layovers, he would play the piano in hotel lobbies and rally other flight attendants for nights out on the town, coworkers said.

On April 5, Gismondi became the first JetBlue employee to die of COVID-19.

Within days, two more JetBlue deaths linked to the coronavirus followed: Pilot Kevin McAdoo, a U.S. Air Force veteran, died April 7. Then, 27-year-old Jared Lovos, a fitness enthusiast who had been a JetBlue flight attendant and transferred last summer to human resources, died April 10.

Across the industry, The Times learned of at least 15 workers who have died from COVID-19 from April 5-13, according to the airlines, unions and interviews with family members and friends. Yet without any central tracking, the true number of deaths in the airline industry is likely to be significantly higher.

An American Airlines gate agent at Los Angeles International Airport, an aircraft mechanic at a Tulsa, Okla., airport, a baggage handler at Dallas-Fort Worth and a food services manager at JFK airport in New York are all counted among the recent dead. And the human toll of air travel is mounting.

Many pilots and flight attendants see these as preventable deaths.

Passenger numbers are down 95% compared with the same week last year. Airlines have made drastic cuts to service. At the same time, they are still offering specials like $35 round-trip tickets from Los Angeles to Chicago. Major airlines are set to receive $25 billion in coronavirus relief funding from the federal government; the bailout requires that carriers maintain baseline service levels.

“We are doing nothing but spreading the disease,” said one American Airlines flight attendant, who asked not to be named because they were not authorized to speak to the media.

Delta emailed flight attendants April 9 telling those with the coronavirus to “refrain from notifying other crew members” or posting on social media, according to an email obtained by The Times. In a statement, a spokesperson for Delta said that the email used “incorrect language” and that the airline’s notification process “protects confidentiality of employees” and “follows — and in some cases exceeds — CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] guidance.”

While policies are inconsistent among airlines, crew members across the industry report that they either haven’t been told when they’ve been exposed to coworkers with the coronavirus, or notification comes too late. Until recently, airlines banned flight attendants from even wearing masks.

Flight attendants want nonessential flights to stop amid coronavirus outbreak

The airlines are breaking no Federal Aviation Administration rules regarding the pandemic. In fact, the FAA has none; it recommends — but does not mandate — that airlines follow the CDC’s guidelines. Pilot and flight attendant unions have blasted airlines for failing to properly notify crew members of exposure, demanding that the FAA mandate CDC recommendations.

The FAA did not respond to detailed questions but referred a Times reporter to a letter from FAA Administrator Steve Dickson. “We are not a public health agency,” Dickson wrote.

All the way through mid-April, the FAA was telling airlines that crew members may continue working “as long as they remain asymptomatic.” But symptoms may take 14 days to appear, and the CDC now says that upward of 50% of people with the infection may be asymptomatic.

The Assn. of Flight Attendants has called for the grounding of all leisure travel, with air travel limited to essential services like cargo and medical flights.

JetBlue said the airline follows CDC guidelines and provides 14 days of paid leave to anyone instructed by a doctor or health official to quarantine, even if a test is unavailable.

“There is nothing more important to us than the health and safety of our crewmembers and customers,” a spokesperson wrote in a statement.

“This is the part that gets me,” said a JetBlue flight attendant, who asked not to be named because they were not authorized to speak to the media, and who was a friend of former firefighter Gismondi. “He was saving lives, and then he retired and went to passing out potato chips and pretzels. And this is what this man is going to die from?”

For 11 hours, flight attendant Jorge Merelles heard the sound of coughing throughout the plane from Rio de Janeiro to Miami on March 15. One woman, in particular, was gasping for air and very pale, with a deep cough like a smoker.

“There were a lot of elderly customers onboard who came from the canceled cruise ships. A lot of them were sick. None of them were wearing masks,” Merelles said.

Merelles and the other flight attendants were not allowed to wear masks at the time.

In our effort to cover this pandemic as thoroughly as possible, we’d like to hear from the loved ones of people who have died from the coronavirus.

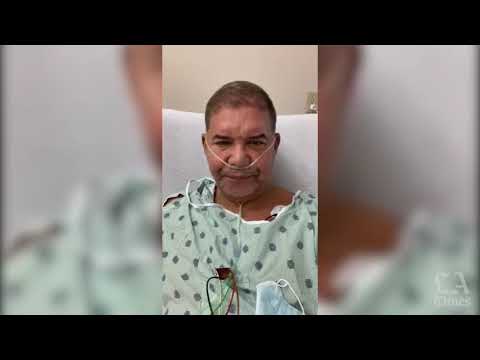

Merelles got home to Miami and then flew six more legs over the course of the next week, traveling back to Brazil, to Mexico, to Los Angeles and St. Louis. On March 23, he started to feel tired. Then came a headache, a slight fever and shortness of breath. The following day, he lost his sense of taste, his fever spiked and his body ached. That night, unable to stand, he went to the hospital suspecting he had COVID-19.

“I was thinking of the Rio flight,” he said.

He spent the next eight days in the hospital, treated as a presumptive COVID-19 patient while awaiting test results.

On the third day in the hospital, Merelles received a FaceTime call from a flight attendant friend, who said he was in the hospital with COVID-19 and his wife was in the ICU on a ventilator with the virus too. Before long, the two men realized they were in the same hospital, FaceTiming one another from three rooms apart.

Flight attendant Jorge Merelles was hospitalized with COVID-19.

It was a sobering sign of how widespread infection had become among flight attendants.

On April 1, the day Merelles was discharged from the hospital, his COVID-19 test came back positive. Merelles said it was only then that his airline started notifying crew members with whom he had flown. But the notification went to coworkers with whom he had worked in the 48 hours prior to the onset of his symptoms.

By and large, airlines aren’t consistently telling pilots and flight attendants when they’ve been exposed, according to pilot and flight attendant unions and interviews with crew members. Or, as Merelles experienced, airlines are waiting too long.

He said it wasn’t until April 15, a full month after his Brazil flight, that his airline called to say there had been confirmed positive cases onboard.

Merelles firmly believes that all aircraft should be grounded, with flights solely for medical purposes, cargo and mail.

“If they have crews, have those crews tested. Check them out. Have a very tight control over this. That’s the only way to get out of this,” he said. “I think we are still spreading it from city to city.”

A long line of cars drove past Gismondi’s house on Long Island on April 11, some with JetBlue scarves flying from the mirror. One by one, Gismondi’s fellow flight attendants slowed down to wave at his wife and family wearing masks and standing in the driveway.

Not far away, a baggage handler from JFK airport was in the hospital with only a few days left to live.

Leland Jordan, an architectural drafter, had moved in 2009 from Guyana to New York City. Working as a baggage handler was the only job he could get as an immigrant.

From 9:30 p.m. till 5:30 a.m., Jordan routed bags from international flights in JFK’s Terminal 4. Lacking health insurance, the 73-year-old worked as much overtime as he could get to pay for his diabetes medication and medical expenses, according to his wife, Juliet.

More than 100 flight attendants on one airline have tested positive for the coronavirus. Have airlines done enough?

On March 17, Jordan fell ill at work and had to be transported to the hospital by ambulance. He was later discharged to his home in Far Rockaway, Queens, near the airport. Feeling better, he went back to work.

Jordan and his coworkers spent their shifts stationed in a confined indoor space, handling all of the international bags. Jordan went to his supervisor to say it wasn’t right that they were not practicing social distancing and had no protective gear, his wife said.

The contractor laid off Jordan and other workers March 24. About a week later, Jordan started coughing. “He said he was just getting a little cold. But we didn’t know,” his wife said.

Then he started getting a headache and grew worse. She called an ambulance April 7. “He walked down the steps very strong and went and sat on the stretcher. I never thought I wouldn’t see him back.”

But Jordan declined quickly. He died April 13. One of his coworkers, a fellow baggage handler at JFK, also died after becoming infected with the virus, according to his union, 32BJ SEIU.

“Everybody was worried about the dangers of COVID,” said Jordan’s wife. “But when you’ve got to work, you’ve got to work. You need money. When that’s the only income you have, you have to work.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.