‘A connection to California’: Reading the L.A. Times’ 1983 Latinos series for the first time

In the summer of 1983, the Los Angeles Times published a series on Southern California’s Latino community. It was produced by a team of Latino editors and writers assembled throughout the newsroom. Stories of success, struggle, art, politics, family, religion, culture, education, agriculture and history were written and published throughout the summer of 1983. In 1984 it won the Pulitzer Prize for public service.

The idea for the project came after Black journalists at The Times did a series, called “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity,” the year before, in 1982.

Despite its accolades, the Latinos series never made its way to The Times’ digital archives. So, when the opportunity to bring it to life digitally for the first time came up, I was eager to be a part of the process. Before the project to bring it online, I had never read the series. I only heard about its impact through other journalists. Since it didn’t exist online, it didn’t exist in my world.

The series mainly focused on the communities of Southern California, but local and national lines are often blurred along the Southwest border in many of the articles. The connections the families in the series have on both sides of the Mexico-U.S. border go beyond immigration. Those connections were made long before a border was established.

In the first article published, “Four generations: Mexico to U.S. — a Culture Odyssey,” a common sentiment among those who were interviewed is revealed: “Mexicans, whose ancestors inhabited the Southwest long before the region became part of the United States, have strong feelings about this land. The Mexican immigrant does not have to cross an ocean. Only a line on the map separates two regions that once were one and that remain connected by long-standing familial, historical and cultural ties.”

It’s a unique feeling in California, where throngs of people from 49 other states come to pursue their careers, to feel foreign, yet familiar.

In the summer of 1983, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Latino community.

The families represented in the series faced that conflict even as their children made their lives in California, while still being treated as outsiders in areas of L.A., Orange and San Diego counties.

Coming from a family and area that made me feel the same way, the series quickly became a page-turner. What was consumed by readers in 1983 over the span of three weeks was devoured in hours.

In 2017, journalist Frank Sotomayor wrote “The Pulitzer Long Shot,” an in-depth, behind-the-scenes look at how the series came together, and ultimately won journalism’s top prize.

At the time, then-Editor Bill Thomas was reluctant to submit the series for Pulitzer consideration, according to Sotomayor.

“Thomas repeated that the series, although a good product, was ‘not the type that wins a Pulitzer,’” Sotomayor wrote. “He said Pulitzers typically were awarded for investigative series that produce change.”

In hindsight, it’s easy to look back and be critical of Thomas’ hesitation. But 37 years later, the idea of representation eliciting change is still not embraced like the 1983 series was when it was eventually submitted.

The thorough recounting of the journey relayed the open hostility the team faced from people in their own newsroom: “During the project, a number of reporters had hurled ethnic slurs our way, such as ‘You guys going to write your stories in spray paint?’”

The irony of the insulting and inappropriate comment is that graffiti art was part of a growing subculture that was strengthening the bonds among Latino, Black and Asian youths during the 1980s. Those bonds were, at times, omitted in the series in lieu of focusing on the relationship between Latino and white communities. But even in those narratives, there were elements of the relationship that revealed a shared pain of inequality among what were L.A.’s minority groups.

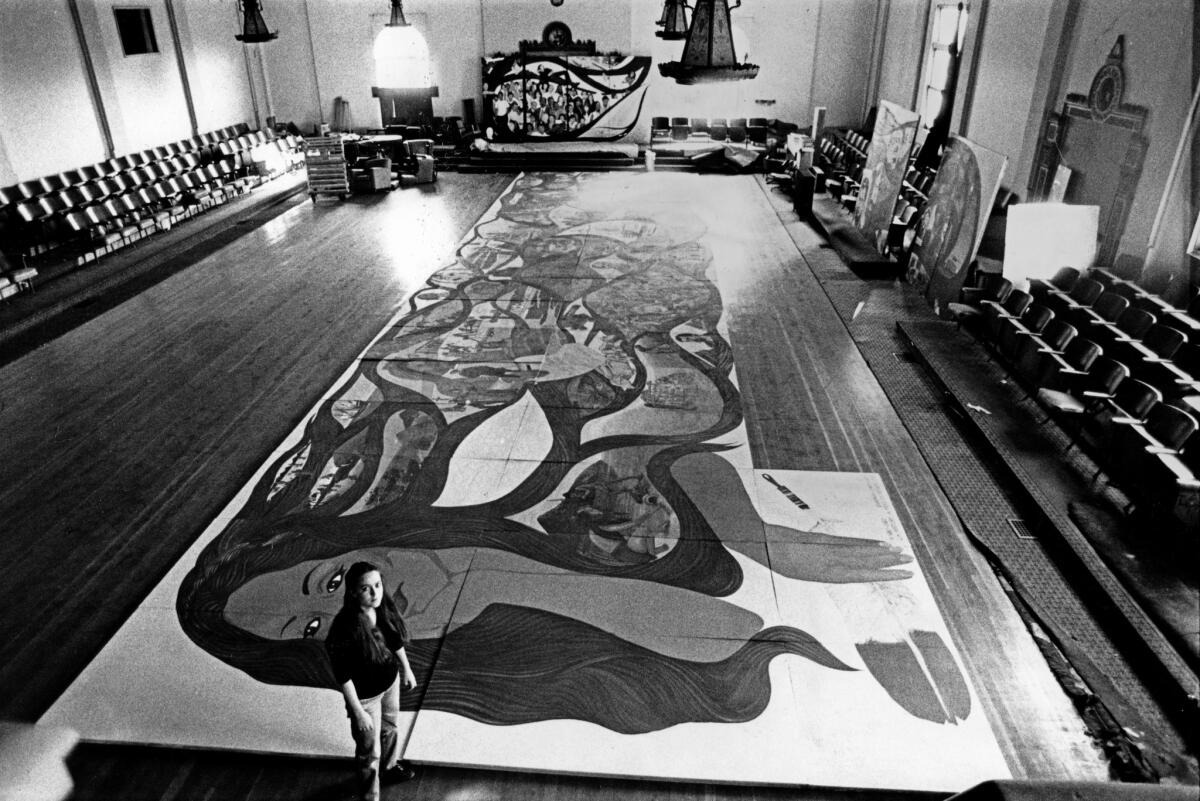

Barbara Carrasco, an artist profiled in “Chicano Art: An Emerging Generation,” symbolized the shared pain in her mural “L.A. History—A Mexican Perspective.”

Her mural depicted a brutally honest account of various historical moments in L.A. interlaced through the braids of a woman’s hair. Among the scenes were the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II and the lynching of Chinese workers in 1871.

Oppression is a big part of California history, but the successes of the same communities that faced the oppression are what makes them all Californian.

My dad’s family came to La Habra from Guadalajara, Jalisco. My mom’s family is fairly new to the area, considering the roots others have laid here. Her dad, a Black man from Mississippi, and mom, who came here from Japan, settled in California after her dad’s military career.

It was easy to fall into an identity crisis, but while reading this series 37 years after it published, I felt a connection to California that made me feel truly at home. The things that used to make me feel like an outsider in certain social circles became marks of pride. The series focused on Latinos, but the universal theme of trying to create a successful life in California is a theme that allowed me to see both sides of my family represented in the series.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.