How bad is all that wildfire smoke to our long-term health? ‘Frankly, we don’t really know’

For weeks, millions of Californians were smothered by smoke from a record explosion of wildfires burning through grass, shrubs, conifer forests, houses and mobile home parks. Eyes watered. Lungs burned. Skies glowed orange.

People suffered sore throats, headaches and chest pains. Many cloistered themselves indoors as pollution spiked to “hazardous” levels, or worse, on the Air Quality Index.

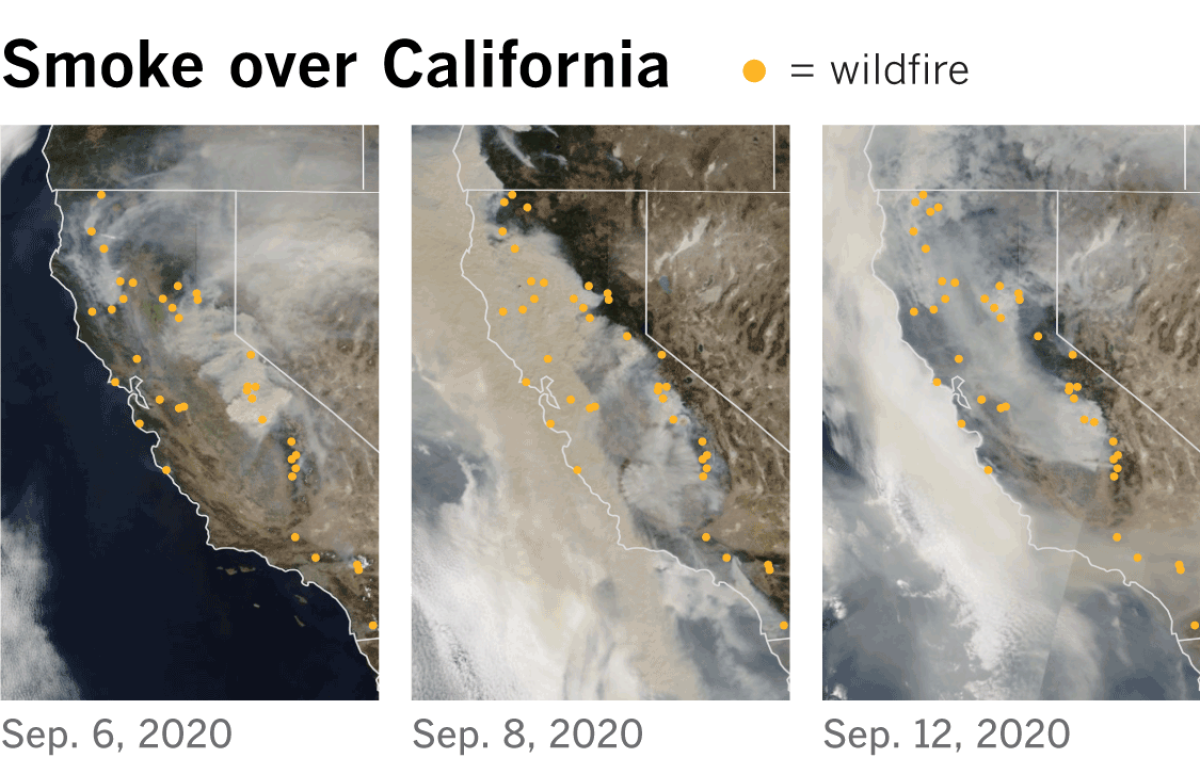

While most people were not threatened directly by fires burning up and down the West Coast, smoke transported health dangers to nearly every corner of the state. State air quality officials are aware of no precedent for so many people breathing such high levels of wildfire smoke for so long.

Even as air quality begins to improve, many remain worried about long-term health impacts.

“Frankly, we don’t really know about the long-term effects of wildfire smoke because community exposures haven’t been long-term before,” said Dr. John Balmes, a professor of medicine at UC San Francisco and a member of the California Air Resources Board.

Health experts are fairly certain that such levels of wildfire smoke did significant harm in the immediate term by aggravating chronic lung and heart conditions, triggering asthma attacks, strokes and heart attacks. Scientists also suspect that heavy smoke has lowered people’s defenses against the coronavirus, and put them at greater risk of severe symptoms.

But the question of lasting health damage remains hazier. Though the link between chronic exposure to the fine-particle pollution in urban smog and long-term health problems is well-established thanks to thousands of studies and decades of research, there has been relatively little research when it comes to wildfire smoke.

Understanding the long-term consequences is critical, scientists said, because wildfire smoke is a growing health hazard, responsible for an increasing share of the fine-particle pollution across the Western U.S. And with climate change warming and drying out landscapes, helping to fuel bigger, more intense fires, you can expect more smoky days in the future.

Unprecedented pollution

In just the last month, fires have generated both the highest readings and most widespread unhealthy levels of fine-particle pollution since continuous monitoring began in the late 1990s, California air quality officials said.

In the first few weeks of the firestorm, about half of California’s population — an estimated 19.6 million people — experienced levels of wildfire smoke exceeding health standards, mostly north of the Grapevine, according to the state Air Resources Board. By last weekend, the smoke had spread across Southern California and to nearly every corner of the state, with almost 95 percent of Californians exposed to unhealthy pollution levels, the air quality agency estimated.

Monitoring data released this week by the Air Resources Board showed that 15 of the top 20 fine-particle pollution readings on record in California have occurred during the fires over the last month. The highest concentration yet came on Tuesday in Mammoth Lakes, where concentrations of tiny soot particles known as PM2.5 reached 660 micrograms per cubic meter — more than 18 times the federal health standard of 35 and beyond the range of the Air Quality Index.

“These are unprecedented levels of air pollution,” said Bonnie Holmes-Gen, chief of the Air Resources Board’s health and exposure assessment branch.

Large areas of California have been hit with heavy smoke in the past. The most widespread episode prior to this year, according to air quality officials, was during the 2018 Camp fire, when unhealthy pollution spread across the entire northern portion of the state. The smoke lasted about 13 days, impacting about 60% of California’s population. Fires in the summer of 2008 also brought weeks of widespread unhealthy smoke to northern and central California.

Like tobacco, without the nicotine

Wildfire smoke is distinct from typical urban smog, and consists of thousands of compounds. Its composition varies widely depending on what type of fuel was burned and when.

A big, hot fire burns material more completely, breaking fuels down to their more essential elements. A cooler fire, one that leaves smoldering black and brown wood behind, can release more toxic particulates, experts say. And a fire that burns homes can release a stew of potentially more toxic chemicals from plastics, furniture and building materials.

As a product of the combustion of wood, leaves and other material, wildfire smoke is closer to tobacco smoke than diesel exhaust, and consists of carbon-based particles with “nasty, complex hydrocarbons on their surface” and irritant gases that are known carcinogens, said Balmes.

“The dose is usually less than inhaling directly from a burning cigarette,” Balmes said. “But the dose makes the poison … and the community is getting a bigger dose than we’ve ever had before because of these multiple days in a row of bad air quality.”

Some of the world’s most intense fires produce smoke that lofts into the atmosphere and wraps thousands of miles around the globe, said Barry Lefero, manager of NASA’s Tropospheric Composition Program, which uses a DC-8 jetliner that circles the globe studying wildfire smoke. With big fires “the smoke goes higher in the air, it’s more buoyant, it can travel farther, but at night the fires lay down, the smoke is trapped and it fumigates the valleys that fill up with smoke.”

Short-term effects

Of all the ingredients in wildfire smoke, the most concerning to scientists are microscopic particles known as PM2.5 because they are less than 2.5 microns in diameter. They can be inhaled deep into the lungs and pass into the bloodstream.

In the short term, those tiny specks of pollution can irritate the eyes, nose and throat and cause coughing, tightness in the chest and difficulty breathing, and even flu-like symptoms in otherwise healthy people. But they pose more serious risks to young children, pregnant women, outdoor workers, the elderly and especially people with chronic health conditions such as asthma, lung disease and heart disease.

Balmes said that such high levels of wildfire smoke along the West Coast have likely increased the number of patients seeking medical care for asthma attacks, heart attacks, strokes and other health problems aggravated by air pollution.

“And the longer we have bad air,” he said, ”the greater the cumulative exposure, and that increases the risk of these adverse outcomes.”

Stanford University researchers Marshall Burke and Sam Heft-Neal did a “back-of-envelope” calculation estimating that smoke exposure has likely caused 1,000 to 3,000 excess deaths and an additional 5,000 emergency room visits in California in the last month.

Francesca Dominici, a professor of biostatistics at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said their estimate is credible and the general approach makes sense.

“There is a large epidemiological literature that shows strong evidence of short-term changes in PM2.5 and increased mortality risk,” she said.

The concerns about increased risk of COVID-19 come from past research showing dirty air makes people more susceptible to contracting similar respiratory infections, such as pneumonia, and of developing more severe symptoms. Scientists suspect that is also happening with the coronavirus.

Even if the number of new cases remains the same, there could be more serious health complications because of the way air pollution inflames the lungs and “just doesn’t allow the immune system to respond correctly to this kind of infection,” said Tarik Benmarhnia, a professor of epidemiology at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography and School of Medicine. “I really hope I’m wrong, but what we may expect to see in the next few weeks is an increase in the fatality rate from COVID-19.”

Long-term risks

Scientists have good reasons to expect that chronic exposure to wildfire smoke may inflict some of the same long-term health damage as typical urban fine-particle pollution, or soot. That type of pollution, which in California is generated mainly by motor vehicles, is linked to an array of health problems, including thousands of early deaths each year.

Wildfire smoke could even be more harmful, said Benmarhnia, who cited studies showing that the same concentrations of fine particles, when coming from wildfires, “seem to be way more toxic for the respiratory system compared to PM2.5 from other sources.”

Scientists don’t know for sure because of a dearth of long-term health research. For all the years of study we’ve devoted to vehicle exhaust and cigarettes, our understanding of this fundamental element in our planet’s existence is in its relative infancy.

The few studies that have been completed have usually involved groups like wildland firefighters. There is research suggesting they have increased risk of heart disease and lung cancer, but that is mostly extrapolated from what is already known about exposure to PM2.5 from other sources of pollution, such as traffic.

One of the most relevant studies followed not humans, but baby rhesus macaque monkeys at a primate research center on the UC Davis campus who were exposed to high levels of PM2.5 pollution over a 10-day period during the wildfires in the summer of 2008. The study found that the monkeys had reduced function in their lungs and immune systems years later, compared to monkeys that were not exposed to high pollution levels as infants.

But even those findings were after shorter exposures, and lower pollution levels than Californians have lived with since August, the Air Resources Board’s Holmes-Gen noted.

Lingering questions

A flurry of new research into the health effects of the smoke is now underway.

Rebecca Schmidt, a professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences at UC Davis, is conducting a long-term study into effects of smoke on pregnant women that began in response to the 2017 fires in Napa and Sonoma. She heard from expecting mothers who were affected by the smoke, dealing with coughs, watery eyes and other symptoms and wanted to know what the science said about the impacts on their developing babies.

“There really wasn’t much out there,” Schmidt said. “There were just a couple studies.”

Schmidt’s project now includes about 400 women who were pregnant during or shortly after wildfires in Northern California over the past three years. She plans to recruit additional participants this year who may have faced even higher, cumulative smoke exposure due to the recent fires.

“What we really are interested in is to see what’s happening long term and whether those early biological responses are going to have long-term impacts, and that we just don’t know yet,” she said. “There’s just very little known about wildfire, specifically smoke exposure, and long-term health impacts.”

Meanwhile, another ongoing study in Montana has reported troubling new findings that suggest wildfire smoke impairs people’s lungs long after the smoke clears.

Researchers assessed the health of people in the small community of Seeley Lake, outside Missoula, which was blanketed with heavy wildfire smoke for 49 days during devastating wildfires in 2017. Follow-up tests showed they had decreased lung function for two years after the fires, with the percentage of residents who fell below normal levels more than doubling in 2018 and remaining low a year later.

As University of Montana immunologist Christopher Migliaccio and colleagues wrote in a study published last month,”these findings suggest that wildfire smoke can have long-lasting effects on human health.”

Smoke waves, climate impacts

Though at least some portion of California’s PM2.5 pollution has always come from fires, in years past most of it has been generated by motor vehicles and industrial sources. But as vehicle emissions decline and the climate warms, scientists expect the bulk of that pollution to come from wildfire smoke within the next few decades.

“We’ve always been exposed to smoke, but it’s getting worse these days,” said Carsten Warneke, a research scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “And we notice it much more as we’re getting all our other air pollution better.”

Another team of researchers coined the term “smoke wave” to describe episodes of high air pollution from wildfire that last two or more days. In a 2016 study, they projected a big increase in the frequency and intensity of smoke wave events that will affect tens of millions of people across the western U.S. if greenhouse gases continue to rise moderately. Northern California and Western Oregon are among the areas “likely to suffer the highest exposure to wildfire smoke in the future.”

California regulators, who have for decades fought a slow but successful war on smog, are also being forced to confront wildfires as an increasing threat to their work to reduce emissions and slow global warming.

“We’re concerned about smoke pollution undercutting all the efforts we’re making to reduce particle pollution and clean up the air,” said Holmes-Gen of the state Air Resources Board.

Scientists also worry about what the future holds because of the role wildfire emissions play in what’s called a “climate feedback loop,” in which the global warming begets more warming.

“Increased global emissions lead to higher temperatures, which then create drier, more fire-prone conditions,” researchers at the World Resources Institute think tank wrote in a blog post this week. “With more fires comes more emissions, perpetuating the entire cycle.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.