San Diego man reunited with wallet lost in Antarctica 53 years ago

SAN DIEGO — In October 1967, Navy meteorologist Paul Grisham shipped out to Antarctica, where he worked as a weather forecaster for a science station and airport on Ross Island. Thirteen months later, he returned to his family in sunny California, but without his wallet.

On Jan. 30, the now-91-year-old Grisham was reunited with his long-lost billfold, which was found behind a locker during the demolition of a building at McMurdo Station, the southernmost harbor on Earth.

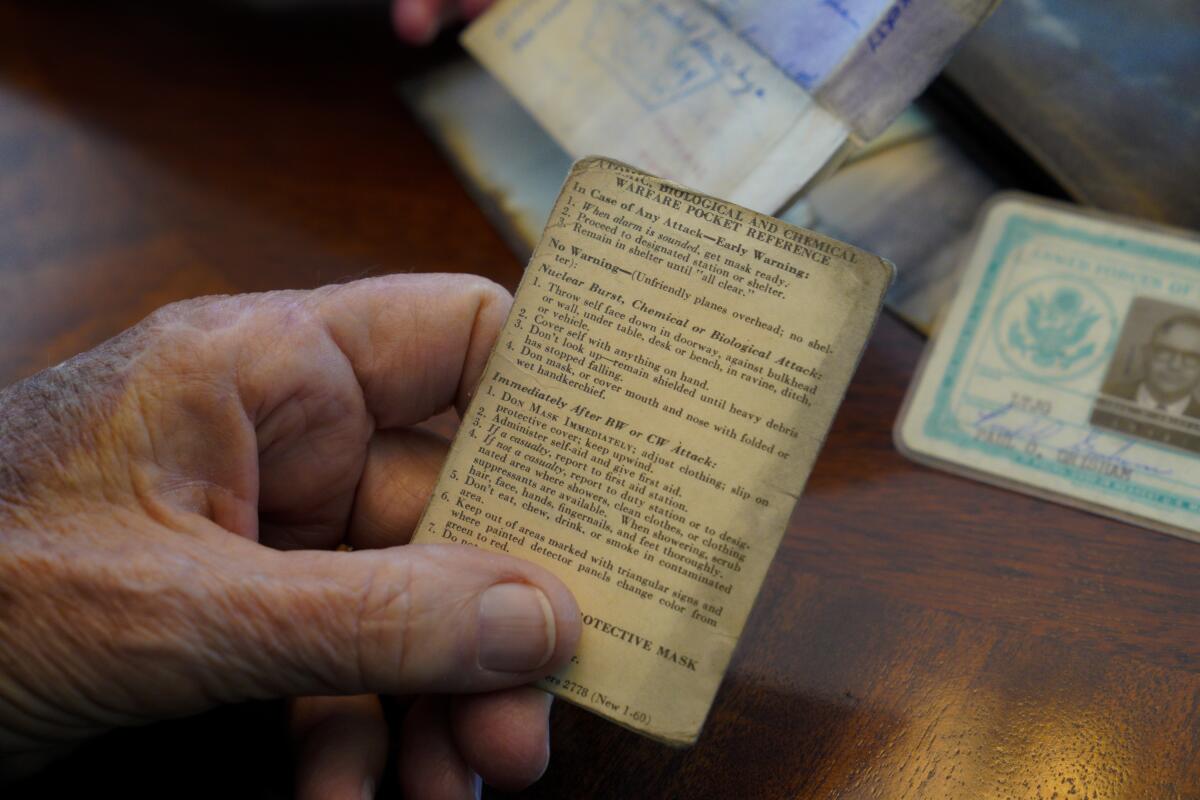

Inside was Grisham’s Navy ID, his driver’s license, a tax withholding statement, a recipe for homemade Kahlua and several items other so-called ice rats who worked at the station might recognize. There was a beer ration punch card, receipts for money orders sent to his wife for his poker winnings at the station, and a pocket reference card with instructions for what to do in the event of an atomic, biological or chemical weapons attack. There was never any cash, as there was nothing to buy at the station.

The brown leather wallet arrived by mail in good condition after a weeks-long journey of emails, Facebook messages and letters among a group of amateur sleuths working to trace its owner. After 53 years, Grisham said he can’t even remember losing his wallet on the continent he calls “The Ice,” but he’s grateful for the efforts to return it.

“I was just blown away,” said Grisham, who lives in the San Carlos neighborhood of San Diego with his wife of 18 years, Carole Salazar. “There was a long series of people involved who tracked me down.”

The team who found Grisham were Stephen Decato and his daughter Sarah Lindbergh, both of New Hampshire, and Bruce McKee of the Indiana Spirit of ’45 nonprofit foundation.

It was the third lost Navy item the trio have returned to families. Last year, Decato got upset when he saw someone’s personal Navy ID bracelet for sale in a shop. He decided to buy the bracelet and, with his daughter’s help, find the owner and return it. Lindbergh found the Facebook page for McKee’s veterans tribute organization and he posted a notice online that helped trace the original owner.

Before he retired six years ago, Decato worked for an agency that does snowcap research in Antarctica. When his former boss, George Blaisdell, heard about Decato’s success with the ID bracelet, he decided to mail Decato a couple of wallets that had been recovered from the building demolished at McMurdo Station in 2014.

Once again, Lindbergh reached out to McKee, who contacted Gary Cox of the Naval Weather Service Assn., of which Grisham is a member. The second wallet belonged to a man named Paul Howard, who died in 2016, but his family was grateful to receive it.

“If it was my dad’s possessions, I would have treasured it as I think they will,” said Lindbergh, whose grandfather served in the Navy. “It was a feel-good thing to do, and both my dad and I have gone to bed thinking that another family was as happy as we are. My grandpa would be so proud, and my dad is proud to have things in their rightful places.”

Looking back on the 13 months he spent in Antarctica, Grisham said it was an unusual, memorable and sometimes tedious experience that he most remembers for the unremitting cold. The average daily temperature was 25 degrees Fahrenheit, but in the winter months, it dropped as low as minus-65 during his stay.

“Let me just say this, if I took a can of soda pop and set it outside on the step, if I didn’t retrieve it in 14 minutes it would pop open because it had frozen,” he said.

Raised in Douglas, Ariz., Grisham enlisted in the Navy in 1948. He started out as a weather technician, then moved up to weather forecaster and was promoted to the rank of lieutenant in Antarctica. His job took him to duty stations in Guam, Hawaii and Japan, and he twice served aboard aircraft carriers in the Pacific.

He spent four years aboard the USS Bennington in the 1950s and ‘60s, and a two-year stint on the USS Hancock during the Vietnam War. He was onboard the Hancock in April 1975 during the fall of Saigon, when the ship’s flight deck crews had to push empty helicopters overboard to make room for new ones touching down with evacuating U.S. military personnel and refugees.

In between those shipboard assignments, Grisham was assigned duty in Antarctica as part of “Operation Deep Freeze,” in which the Navy provided logistical support to civilian scientists on the frozen continent. At the time, Grisham was in his mid-30s and married with two toddlers.

“I went down there kicking and screaming,” he said.

Grisham said it’s hard to grasp the vastness and remoteness of Antarctica. It’s the size of North America, and the journey to get there by ship from New Zealand is 1,100 nautical miles. Most of Antarctica is covered with ice up to 10,000 feet thick, but McMurdo Station is one of the few places that sit on an exposed landmass of volcanic rock.

During Antarctica’s summer months, which are our winter months, Grisham said there were as many as 1,100 workers at the station. But during the Antarctic winter, the on-site staff shrank to 180 because sea ice and subfreezing temperatures made travel and supply runs impossible.

During the winter, all of the food was canned and workers passed the time playing cards, chess, the backgammon-like game of acey-deucey and bowling at a two-lane alley. Grisham said his sole luxury was a daily after-work martini. Once a week he talked to his wife, Wilma, via a voice relay through two shortwave radio operators.

The year’s highlight was a morale-lifting visit from Sir Edmund Hillary, the New Zealand mountaineer who summited Mt. Everest in 1953. He’d traveled to Antarctica that year for a climbing expedition.

In 1977, Grisham retired from the Navy and settled in Monterey, where Wilma passed away in 2000. A year later, while vacationing in Paris, he met Salazar, who lost her husband, Gil, in 1995. They struck up a conversation on the bus to Orly Airport and five weeks later he came to visit her in San Diego. They married in 2003 and have four adult children between them.

McKee, with Indiana Spirit of ‘45, said he’s delighted to know that Grisham was pleased with the return of his wallet. An Air Force veteran himself, he knows the value of military mementos.

“I have a deep love for those that serve and their stories,” McKee said. “Something such as an old wallet can mean so much to someone with the memories that item holds.”

Kragen writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.