What city do you live in? Don’t say Hollywood

What city do you live in?

Are you sure?

If you said you live in the city of Van Nuys or the city of Hollywood, thanks for playing our game, and we have some lovely parting gifts for you.

Toluca Lake and Silver Lake, Brentwood and Hollywood, Harbor City and Panorama City — none is an actual city. They are all suburbs, parts of our great city of Los Angeles family.

It’s no surprise when Angelenos don’t know that. The city is so big — even the numbers vary by 30 or 40 square miles — its edges so raggedy, and it grew like a puzzle, filling in bits here and chunks there, that it defies a single sense of community. You can drive 50-plus miles from the rustic reaches of Chatsworth in the northwest San Fernando Valley to the harbor’s edge in San Pedro and still be in the city limits.

A few years back, a then-city council member named Mitch Englander told the Daily News that when he asked a bunch of fourth-graders where they lived, “they said Northridge or Porter Ranch. When I asked them if they lived in Los Angeles, they all said no.”

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

That geo-anonymity is why we have crafted hundreds of distinct neighborhood identities, cobbled together from the names of venerable developments, or natural features, or community characteristics, or wishful thinking.

We are all Hollywood, in the sense that we are aspirational and willing to remake ourselves. We do this so often, in fact, that in 1991 the New Republic magazine accused us of being “all Norma Jean Bakers trying to be Marilyn Monroes.”

Ten of L.A.’s neighborhoods were in fact once bona fide cities, and most ended up surrendering their independence to L.A. in exchange for adequate water and dependable public services. Here they are, with the tombstone dates of when they began and ended their cityhoods.

Wilmington, 1863/1907-1909

Created by 19th century pioneer Phineas Banning, it was briefly “North San Pedro” before becoming Wilmington in 1863. A military town, a port town, and a railroad town, its formal cityhood came only two years before it got hitched with L.A., in 1909. Banning’s stand-alone town is gone but you can still visit his fancy-for-1863 house.

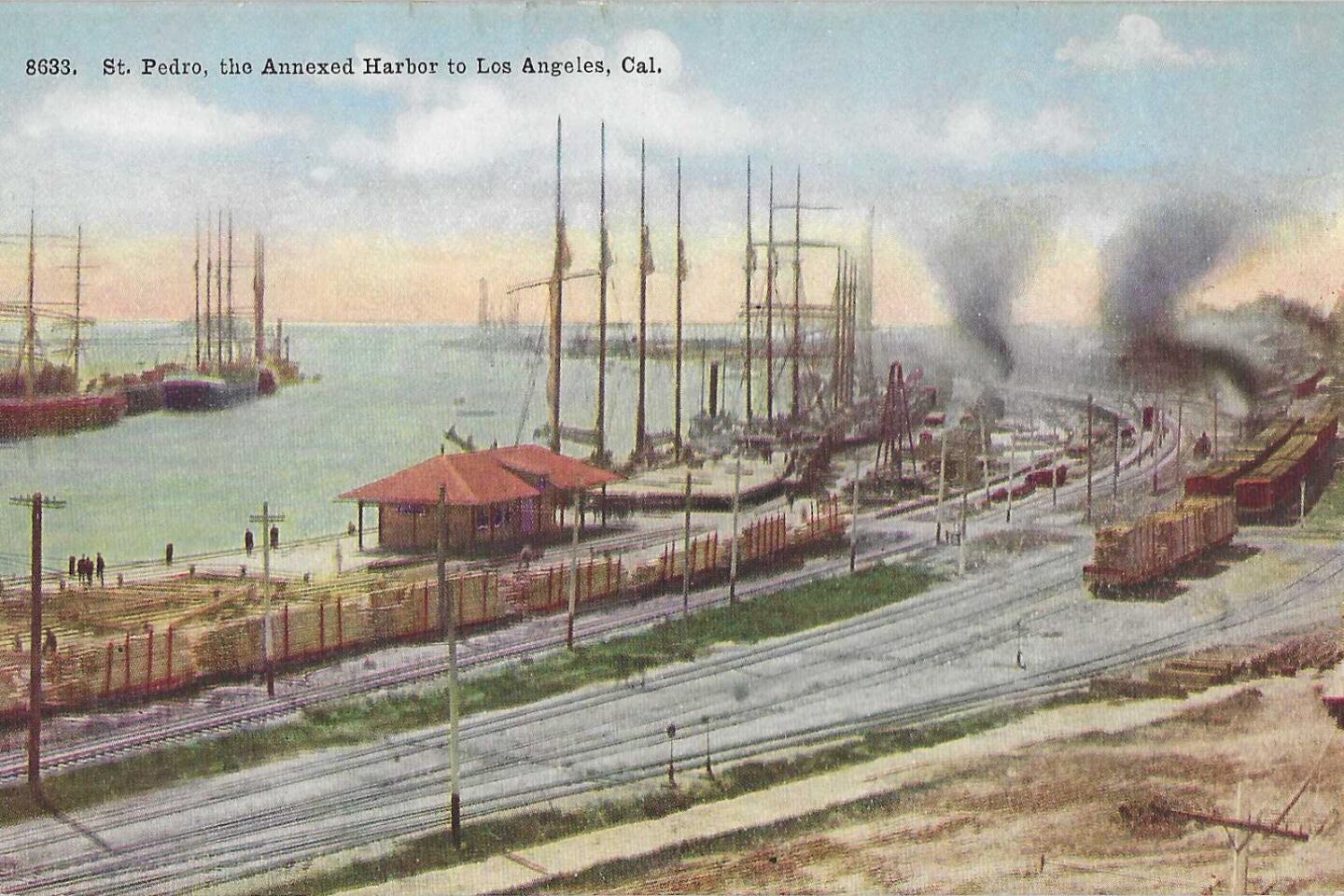

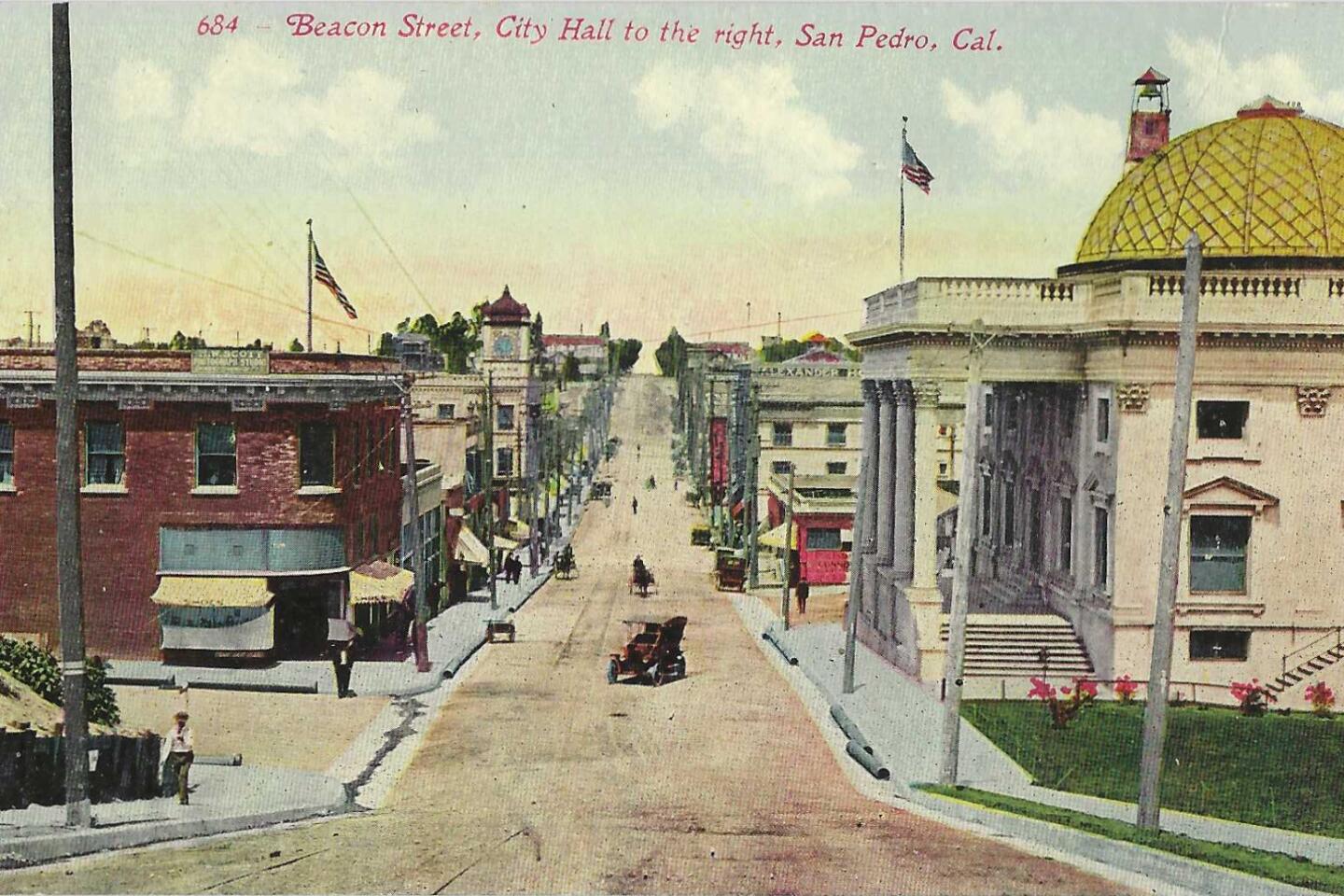

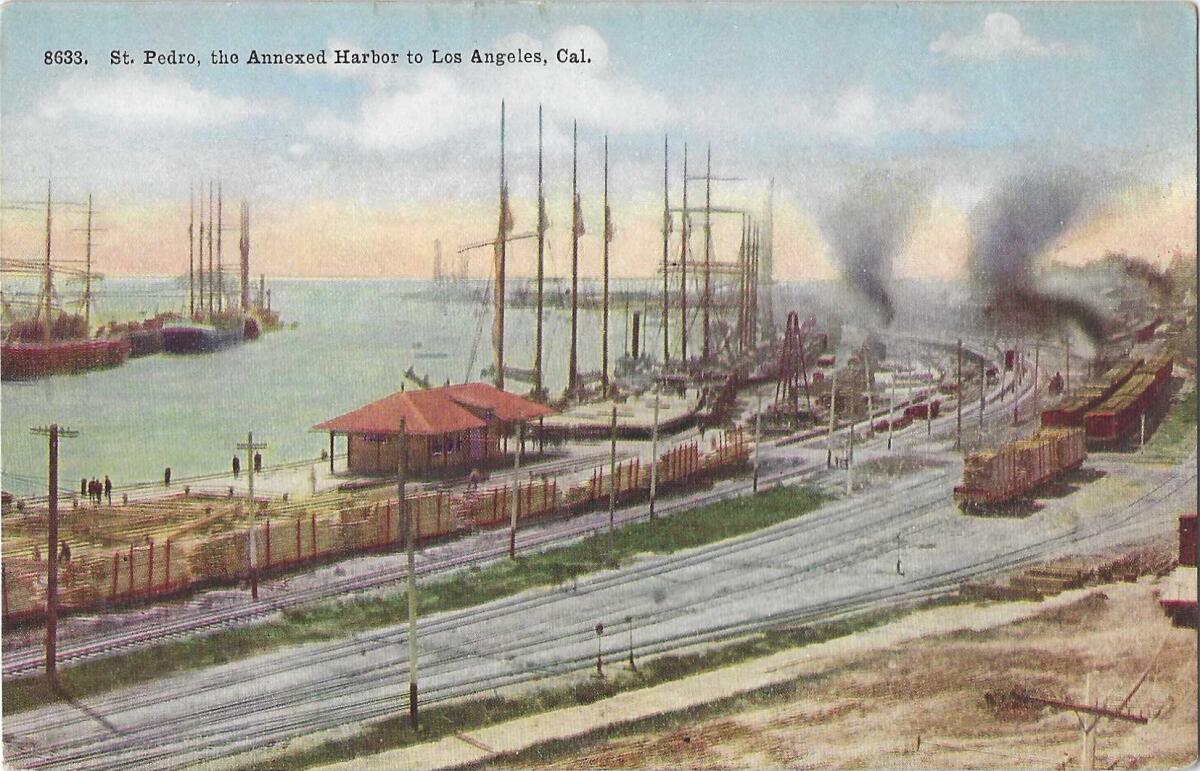

San Pedro, 1882-1909

The port that Santa Monica didn’t become, a place so coveted by L.A. that in 1906, the city engineered a marvel of gerrymandering, a spacewalk tether of land four blocks wide and eight miles long, to tie the bulk of the city to San Pedro and its harbor dreams. It was called the “city strip” and the “shoestring strip,” but “strip” sounds louche, and around 1984 it was renamed, primly, “Harbor Gateway.” As for San Pedro, it had a civic character long before it joined L.A., in 1909. It remains a foundationally diverse town, settled by, among others, Eastern Europeans, Italians, Portuguese, Greeks, Mexicans, and, before World War II, Japanese. Disappointingly, it’s a fishing town not named for St. Peter, the fisherman-turned-apostle, but for some later bishop, who probably did not pronounce his name as the locals do: “Pee-dro.”

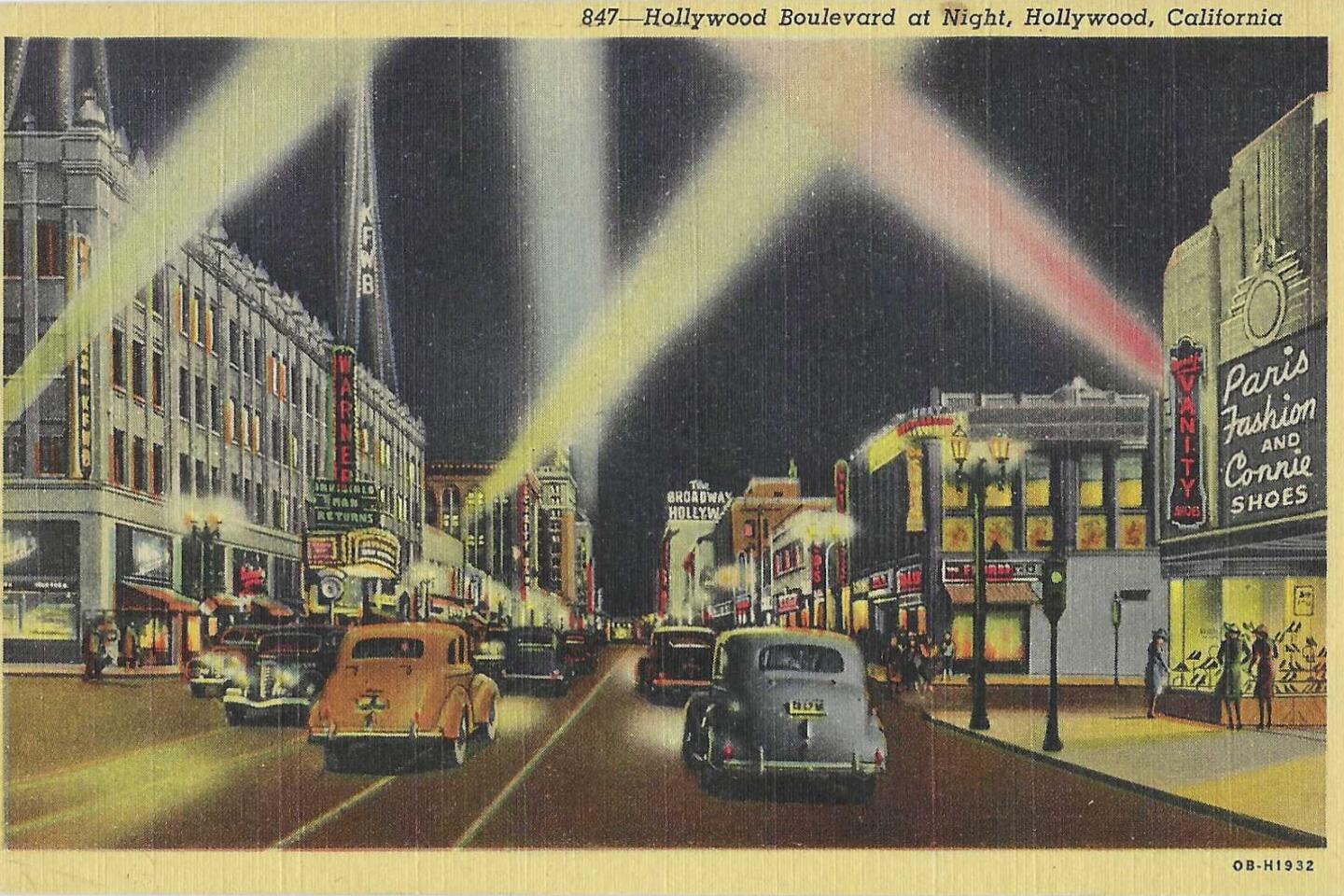

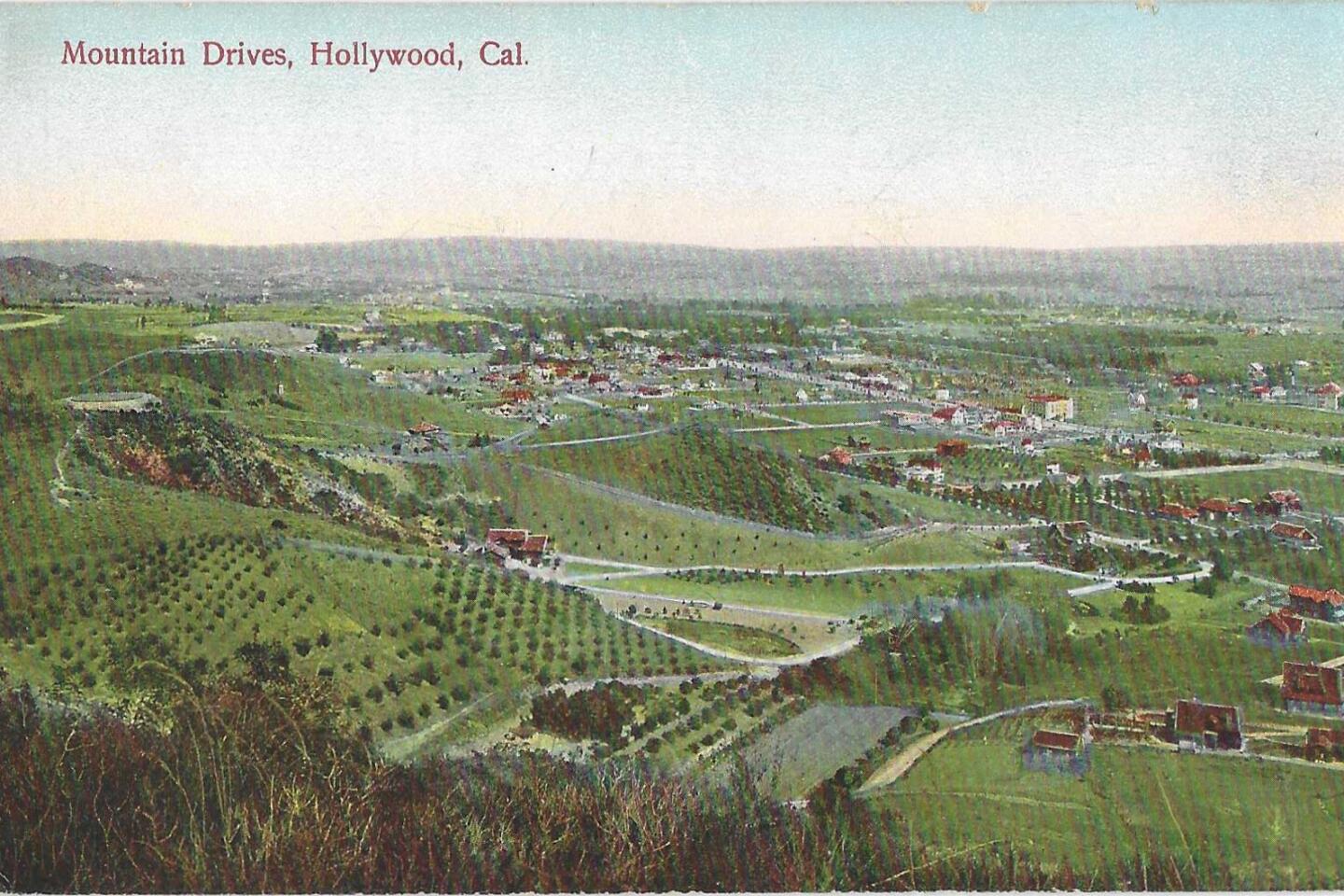

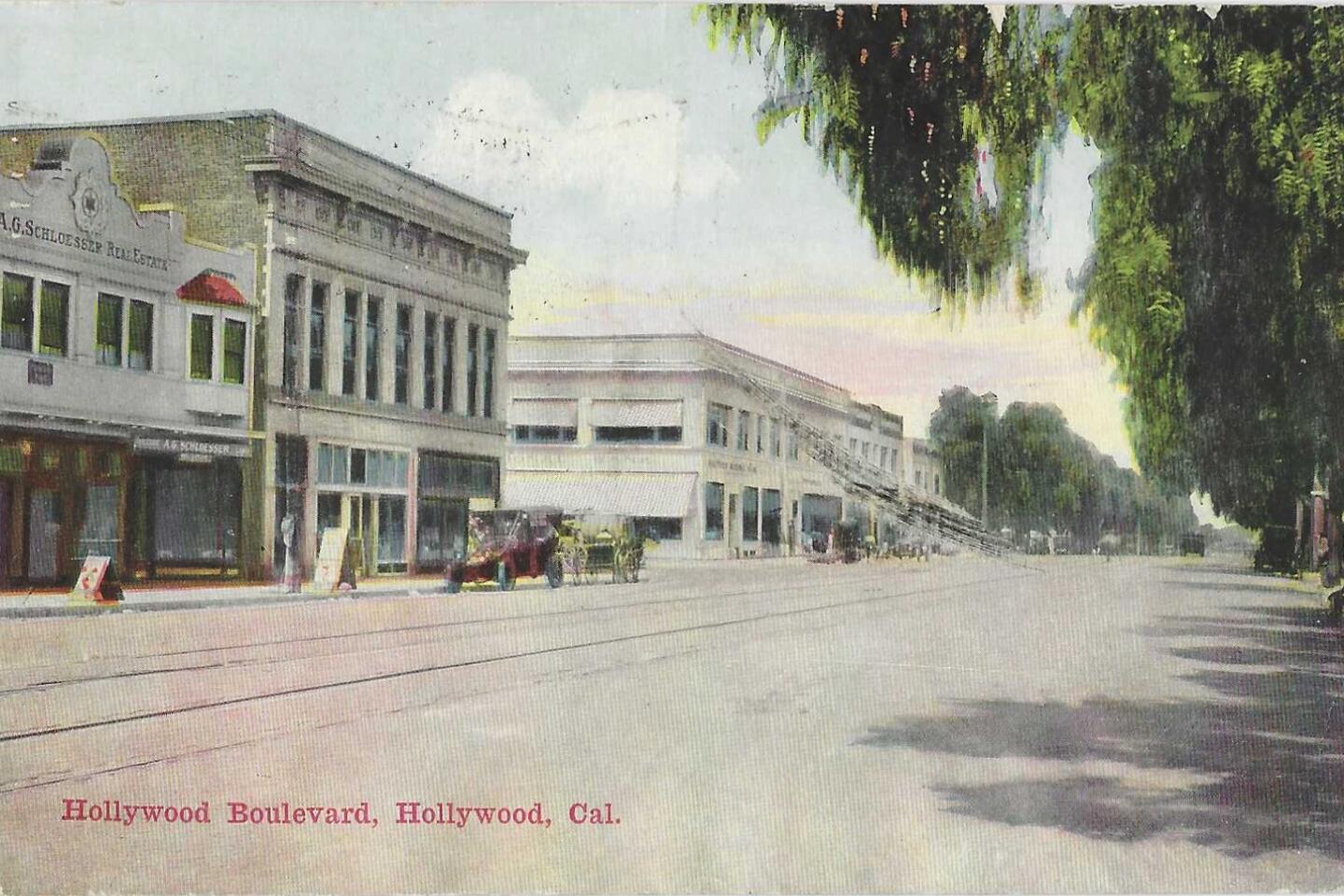

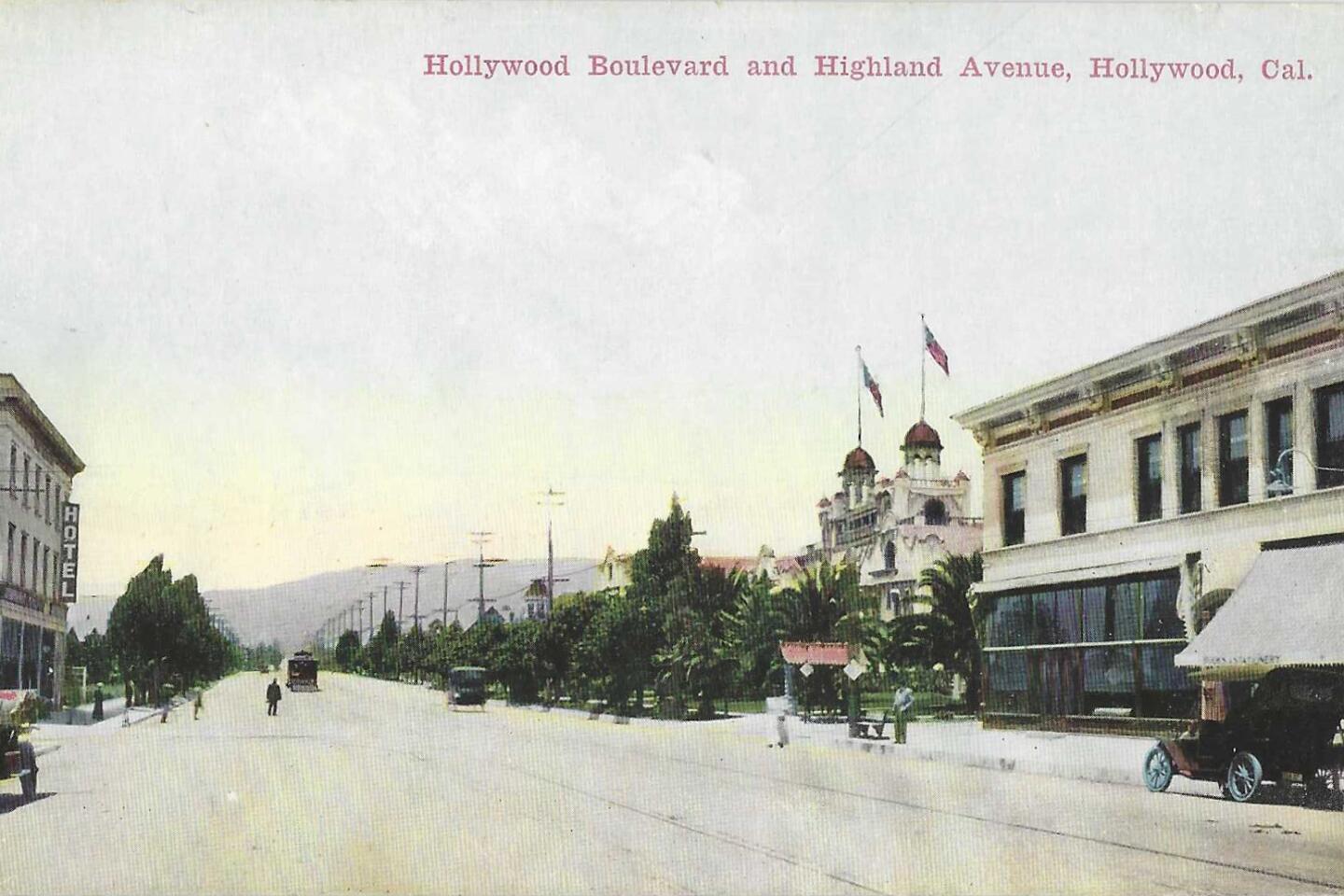

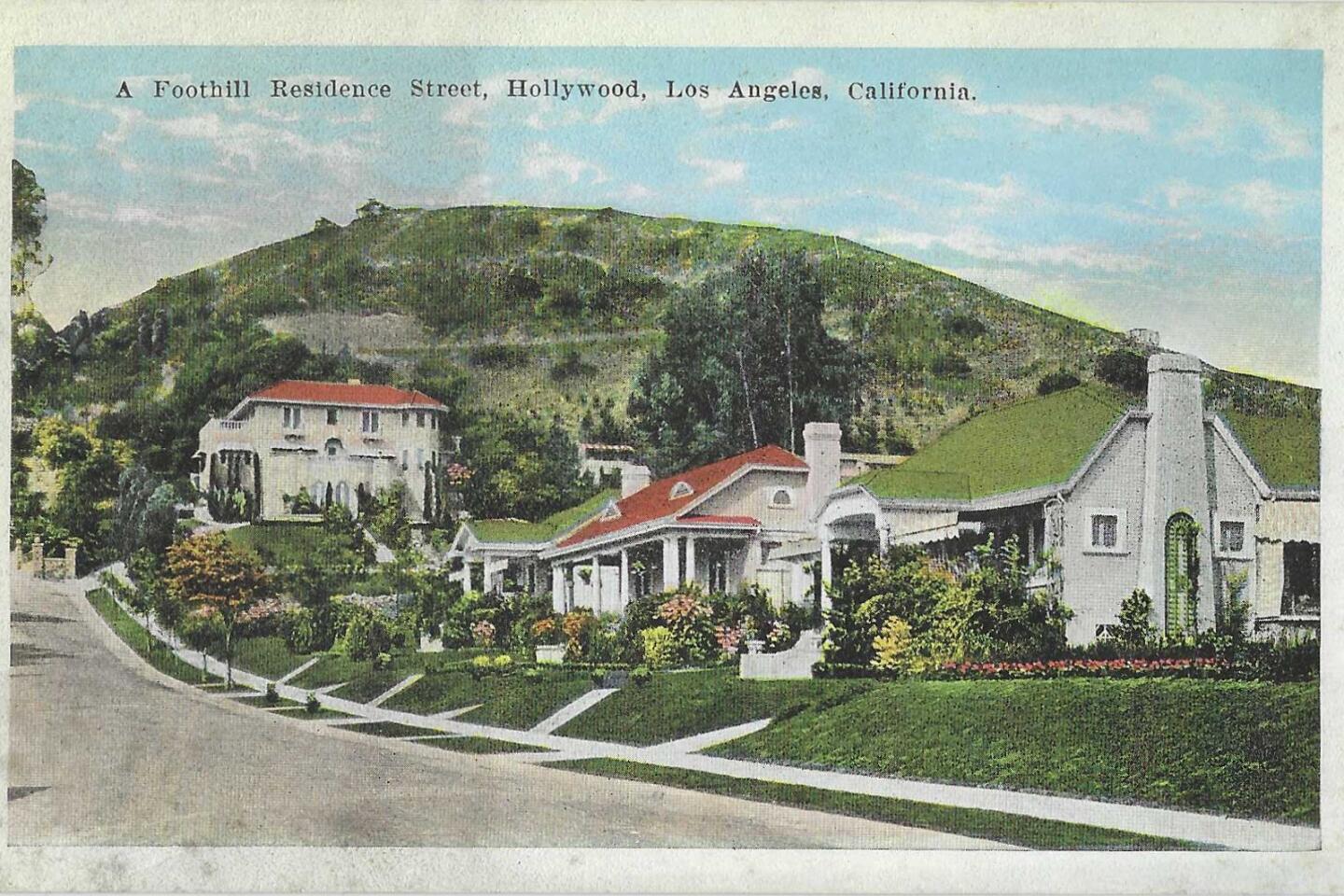

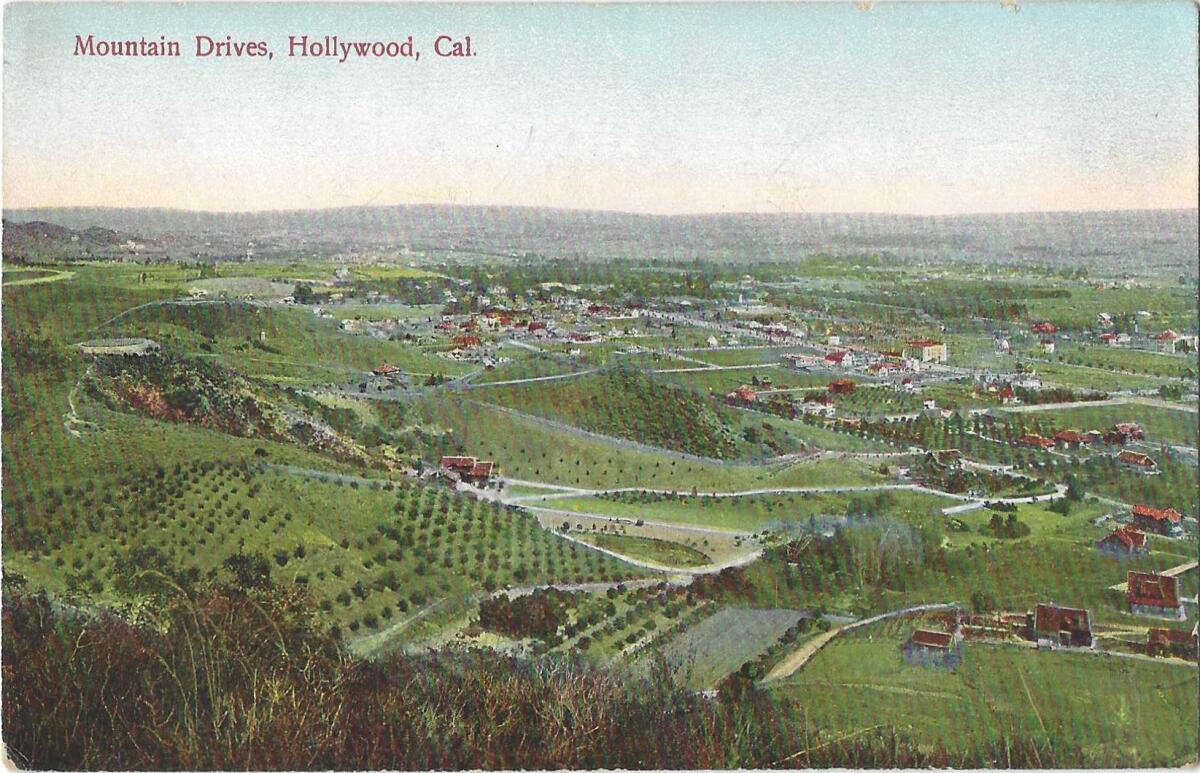

Hollywood, 1903-1910

The platinum-blonde tail wagging the municipal dog. L.A.’s 1960s and early ’70s mayor, Sam Yorty, told me that when he traveled abroad, people asked him, “Los Angeles, Los Angeles — is that anywhere near Hollywood?” Original Hollywood aspired to be as rich and dignified as Pasadena, and thus it banned liquor; maybe its residents’ thirst for something besides water also ended its city status.

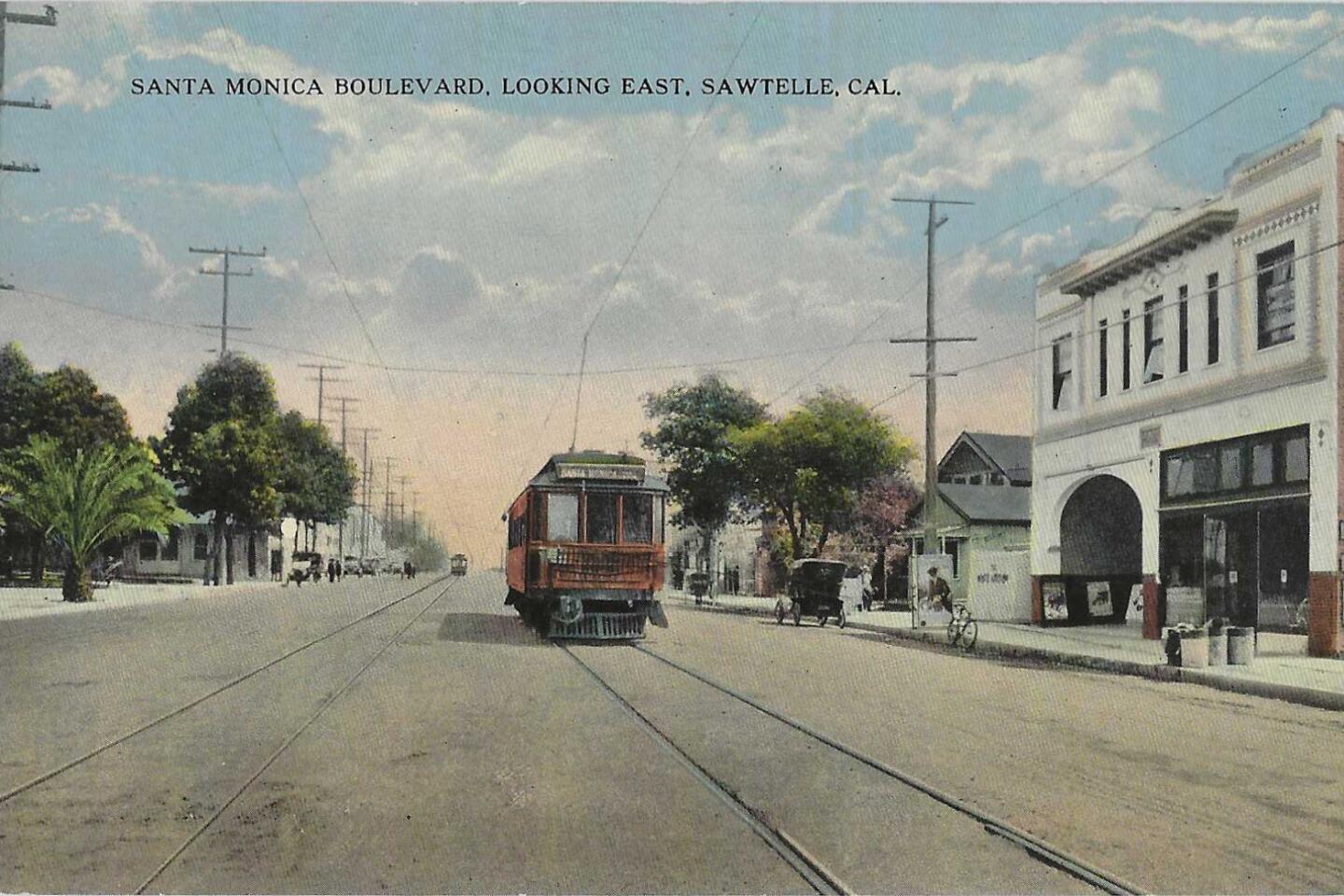

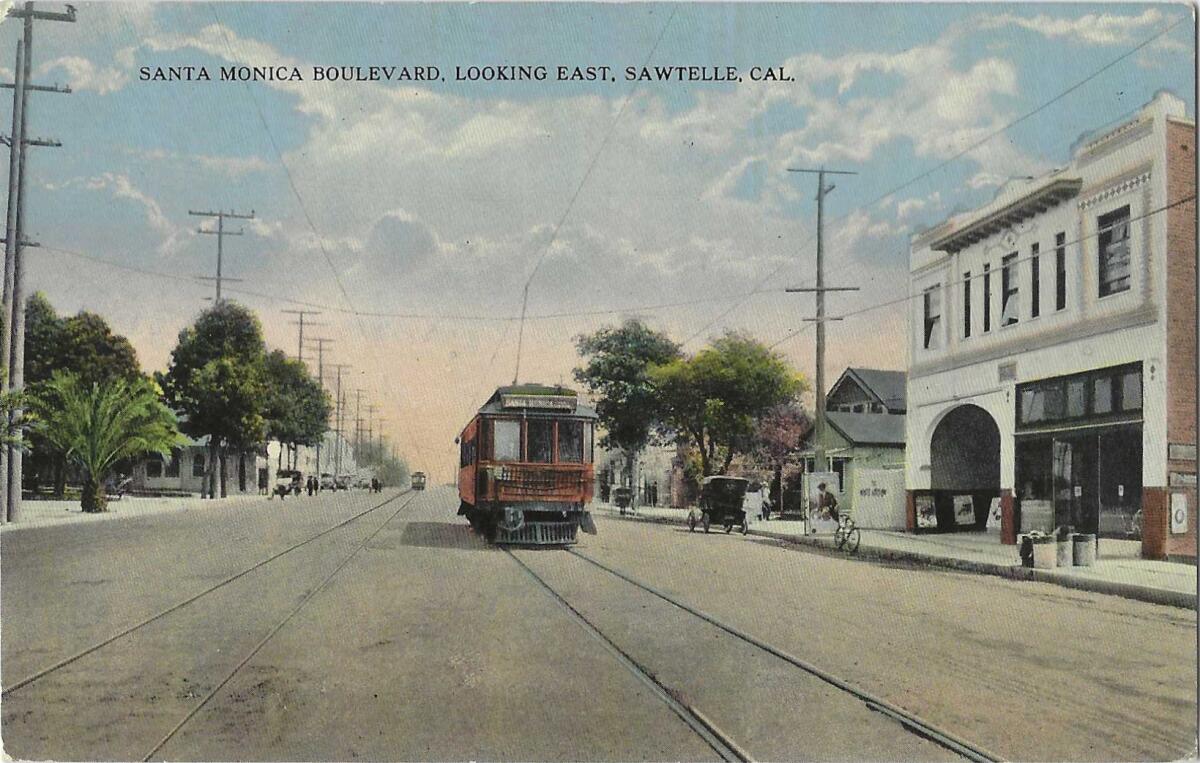

Sawtelle, 1896-1918

Founded by Congress as a soldiers’ home, and here you still find a massive Veterans Administration compound. In 1917, Sawtelle chose — by just three votes — to join L.A. The bloody-minded Sawtelle council refused to recognize the vote and stubbornly held pointless meetings, until Sawtelle took another vote, in 1922, to confirm the first. From World War I and then after World War II, Sawtelle’s nursery gardens were the core of its durable Japantown population.

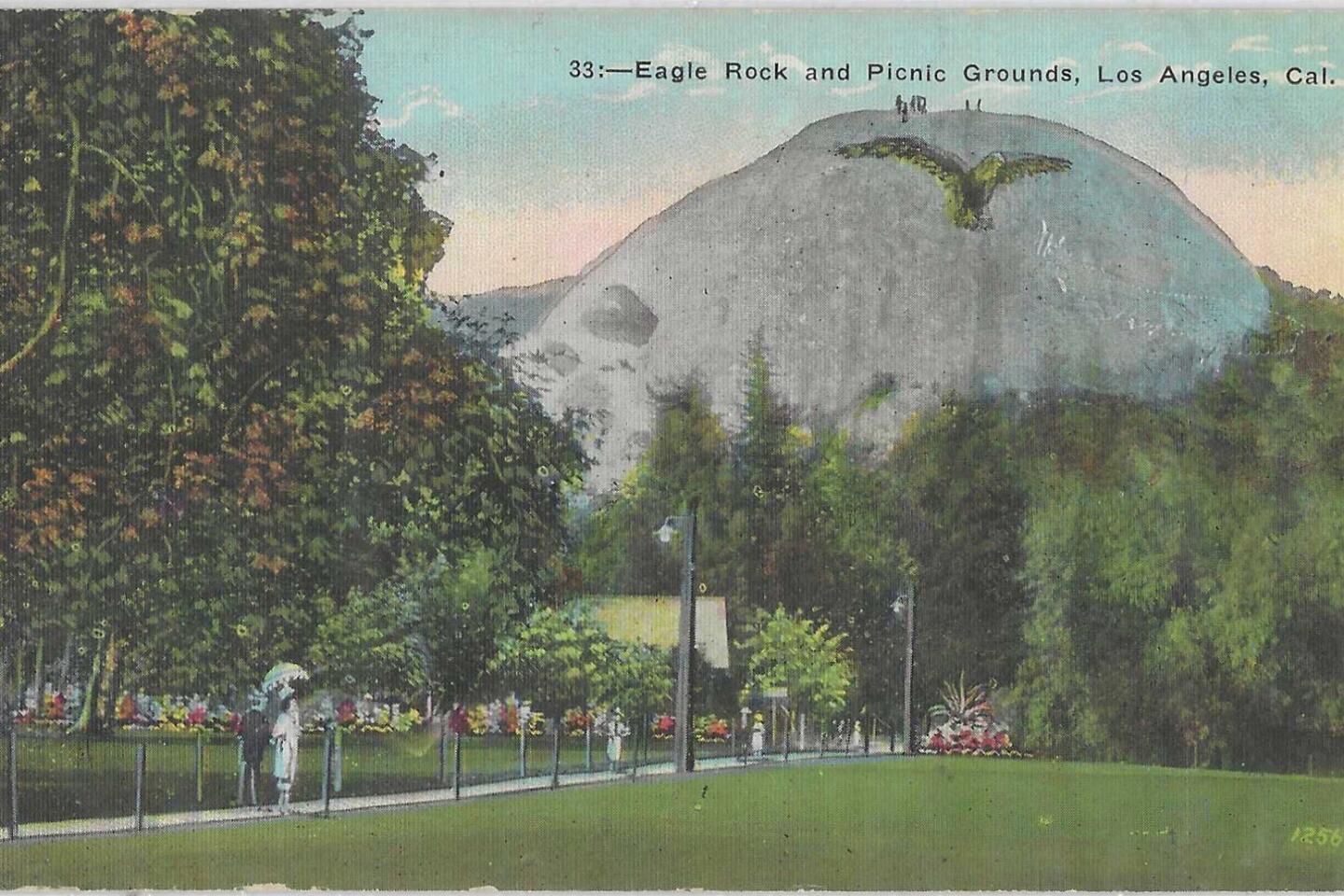

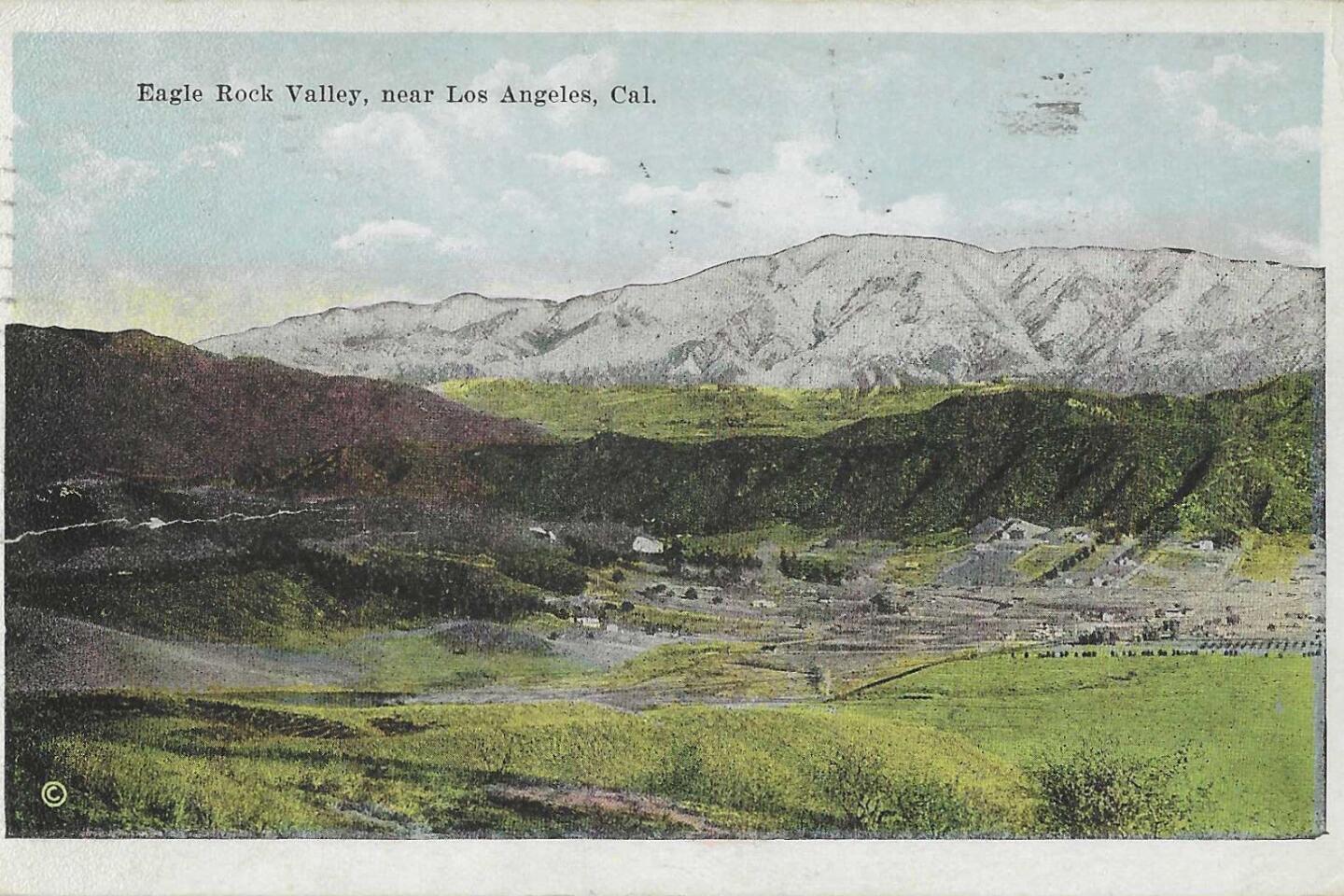

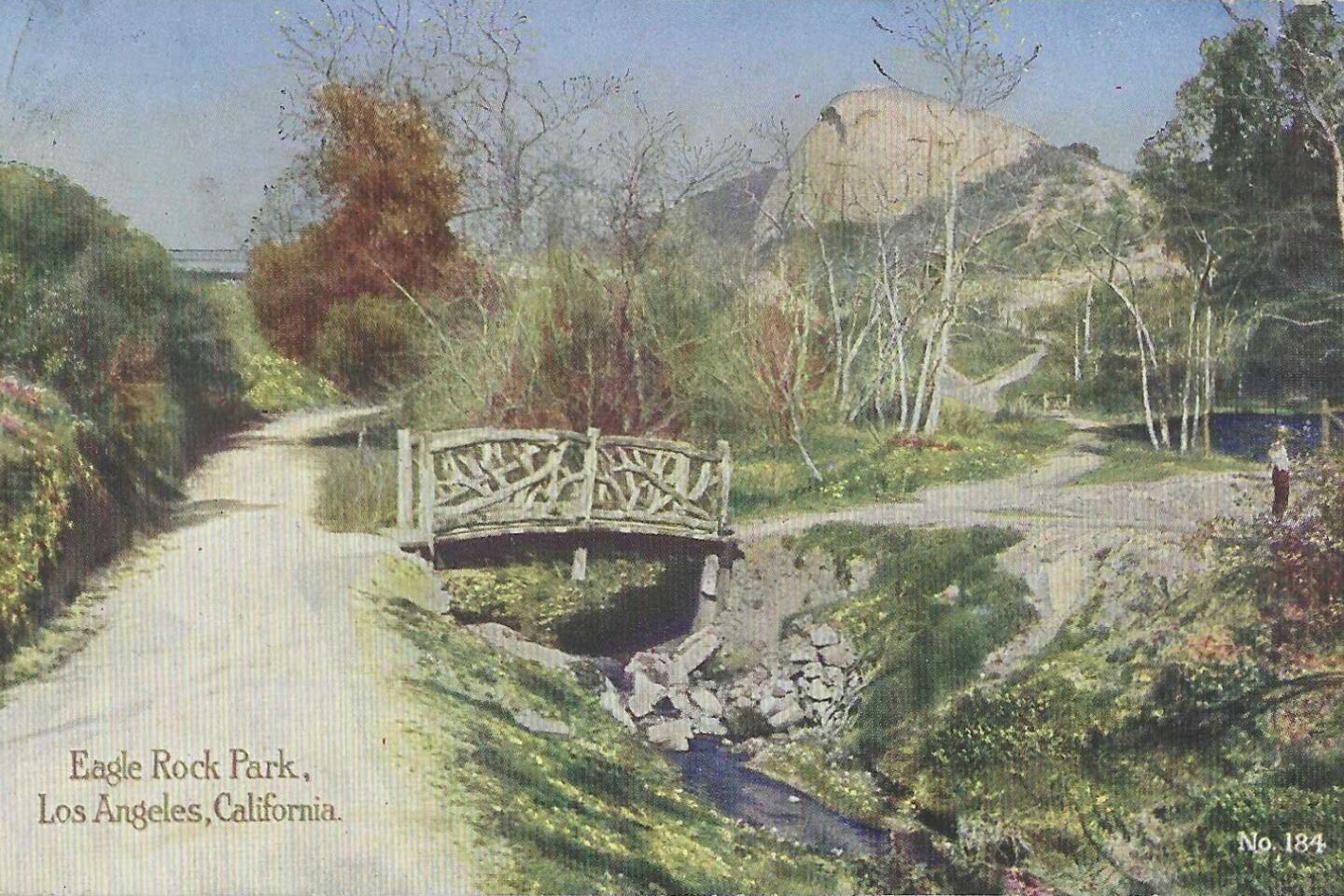

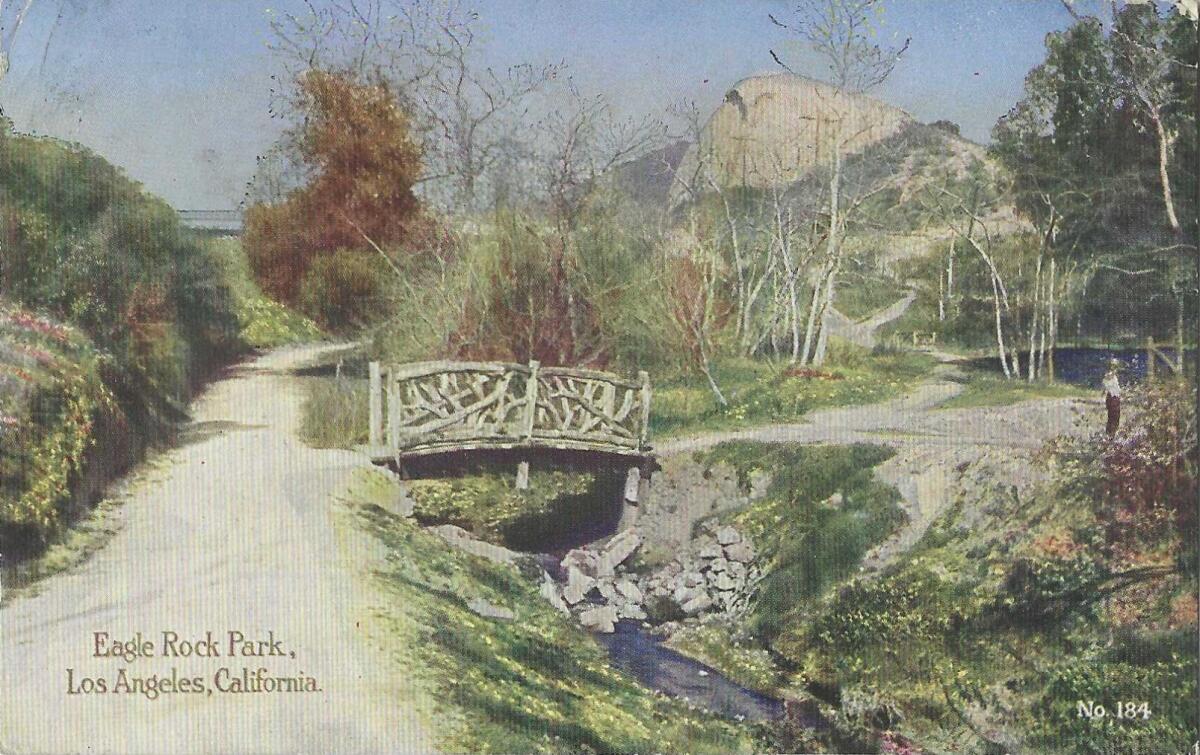

Eagle Rock, 1911-1923

A go-getter community from the mid-1880s and a dandy place to grow strawberries. Its attractions endowed it with more residents than water, thus its vote to Los Angelize in 1923.

Hyde Park, 1921-1923

Centered at Hyde Park and Crenshaw boulevards, happy as its own community from 1887 until big bad L.A. came sniffing, which is why, in 1921, it hastily voted to incorporate, and then two years later gave in to the big boy.

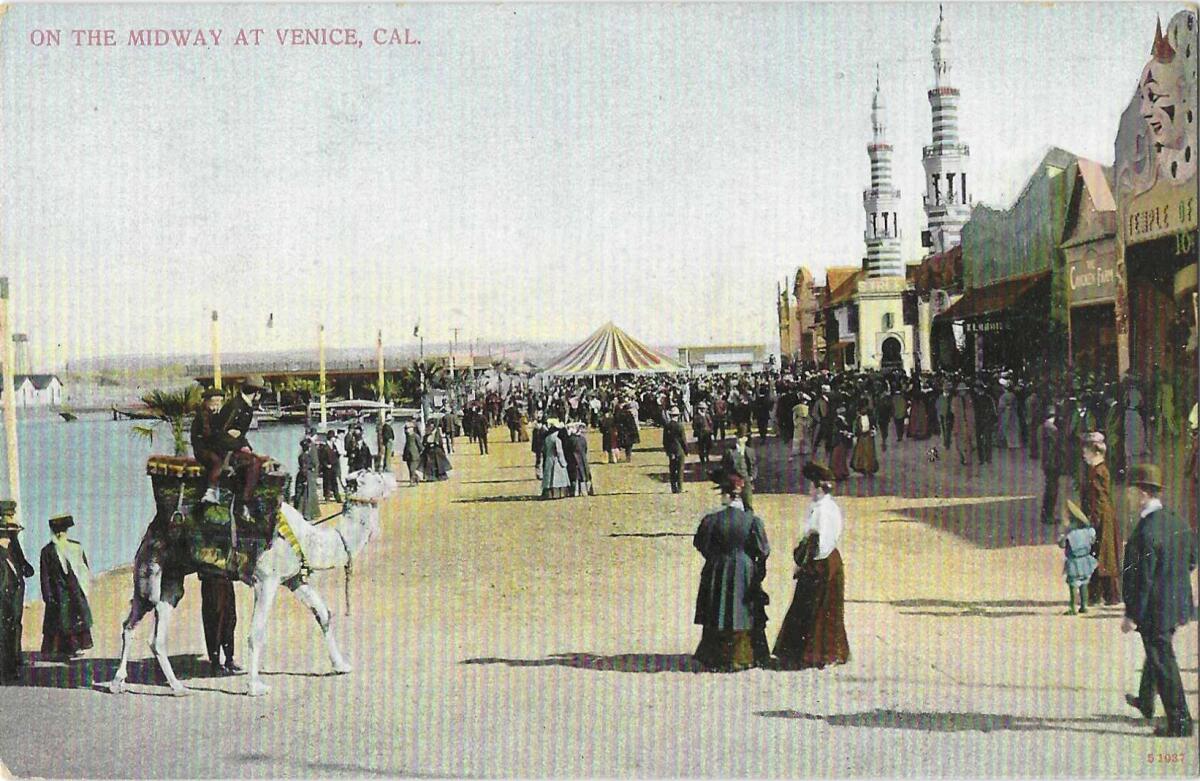

Venice, 1904/1911-1925

Like Hollywood, once more famous than the city that ended up taking it over. In one of those messy business-partner wrangles, some of Venice became the city of Ocean Park in 1904, renamed as Venice in 1911. When Prohibition killed off liquor licenses, it also emptied out Venice’s tax tills, and in 1925, one of Southern California’s most engaging communities threw in the bar towel.

Watts, 1907-1926

Named for its still-surviving train station, and conceived as an experiment, an affordable place for diverse, working-class neighbors to raise their own poultry and produce. But its two square miles had no real industry so, like Venice, it eventually turned to liquor licenses and pool halls to support itself, until it too voted to join L.A.

Sabato “Simon” Rodia’s Watts Towers are more famous than any Los Angeles skyscraper.

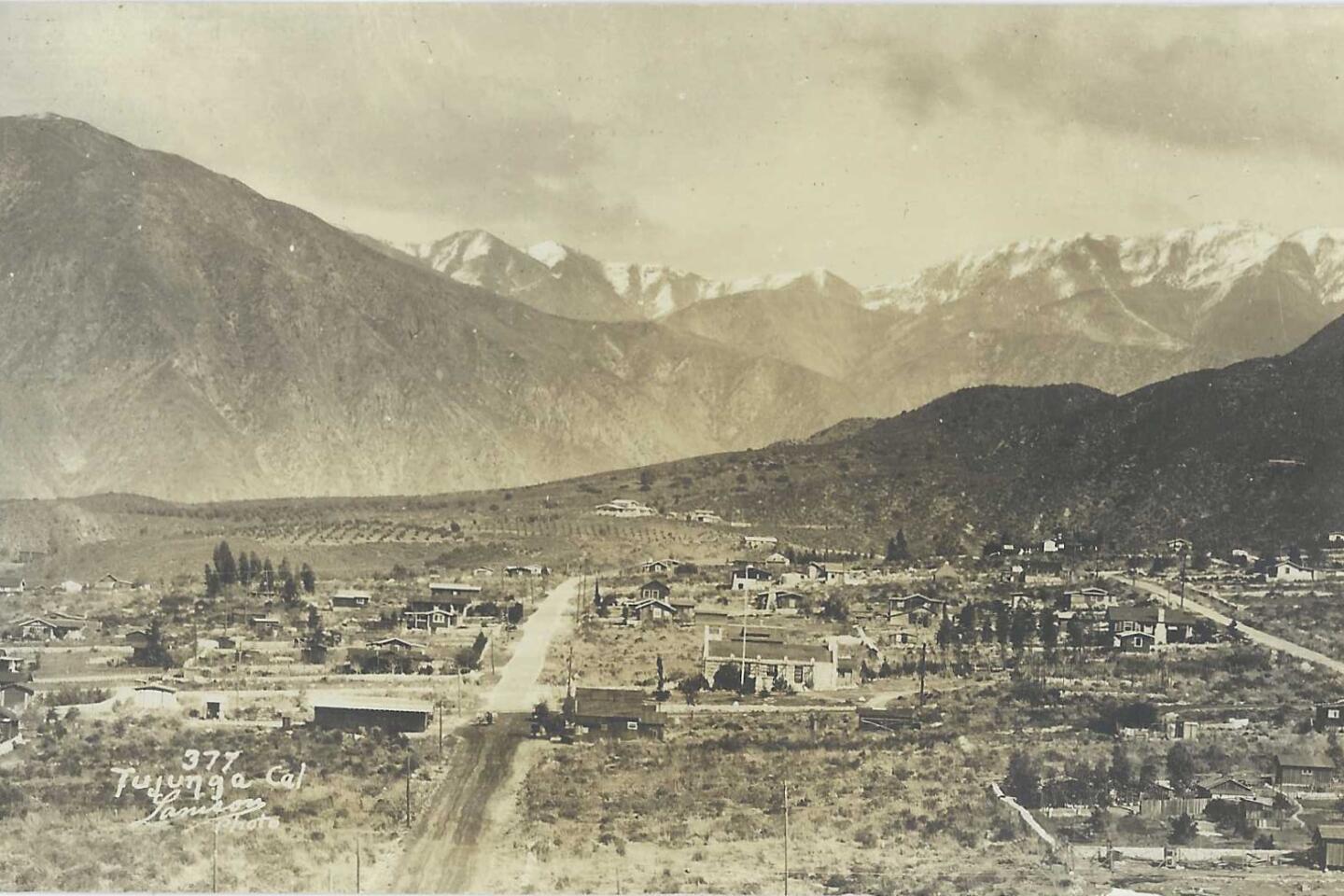

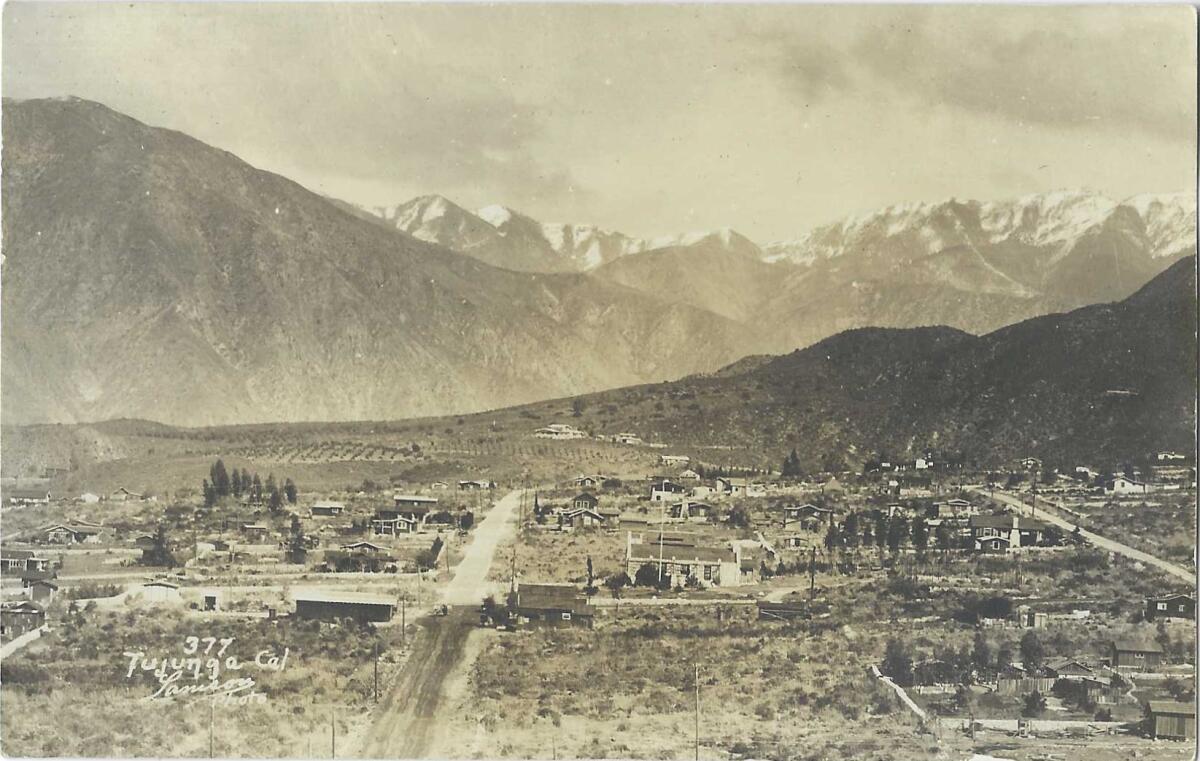

Tujunga, 1925-1932

One of Southern California’s heroic, doomed utopian colonies, founded in the 1880s to be a self-sustaining settlement of idealists and individualists, some of whom built their own striking houses of local stone. Here too, municipal thirst prevailed, and Tujunga voted itself into L.A.’s embrace in 1932, over the mutterings of old-timers that ringers had been brought in to swing the vote.

And my favorite, Barnes City, 1926-1926

Brief as a celebrity marriage, Barnes City existed for all of seven months. Circus owner Al Barnes had moved his circus and its animals from Venice to his land in what is now chiefly Mar Vista. He ginned up a city, so wrote historian and architect Daniel Prosser, as “a legal device to protect a circus and zoo from attempts to regulate its activities.” Of voters who said “yes” to cityhood in February 1926, maybe half worked for the circus. Most of the city’s other 1,500 or so residents also worked for the circus, but they had four legs. While the circus was away on the road that summer, the remaining two-legged residents voted to dissolve Barnes City. Barnes grumpily moved his menagerie to the San Gabriel Valley.

Long before Disneyland and Magic Mountain, Southern California was home to some pretty wild amusement parks, including those with lions, gators and, as one unlucky person discovered in the 1970s, an actual dead guy.

Apart from these former cities, L.A. has hundreds of names for neighborhoods, some only a few blocks in size, drawn from old maps, and many with those distinctive white-on-blue official city signs.

Some places bear the names of streets or features — Larchmont, Silver Lake, Pacific Palisades — or of populations, current or original — Little Tokyo, Koreatown, Historic Filipinotown, Little Ethiopia and more.

Some are just arrant fantasy. Sherwood Forest has no forests and no heroic outlaw, but it took the older neighborhood name when it divorced Northridge in 2017.

North Hills lacks hills and is west, not north, of the Sepulveda neighborhood it broke away from. But then — I hope I have this right — the rest of sad, sad Sepulveda was allowed to become North Hills too. That ticked off North Hills, which then took the name North Hills West — west of the 405 Freeway — and that left the left-behind Sepulveda to call itself North Hills East. Thus, Sepulveda ceased to exist.

The San Fernando Valley is a champ at this “internal secession.” It’s like reading the “begat” books of the Bible: In 1998, about 60 blocks of Van Nuys rechristened itself Valley Glen. Lake Balboa also name-seceded from Van Nuys, even though the actual Lake Balboa is in Encino. West Hills was carved out of Canoga Park, whose original name was Owensmouth. Valley Village came out of a rib of North Hollywood, which hipped itself up as NoHo, but was born as Lankershim, for an early Valley wheat grower whose son-in-law was named Van Nuys. Way to keep it in the family.

More often than not, seceders get accused by secedees of being bad neighbors, of leaving problems behind instead of trying to fix them, of gentrifying and boosting their own real estate values at the expense of their ex-neighbors’.

Can you handle more? There are nearly 30 L.A. neighborhoods with “wood” in the name, conjuring that sylvan vibe; three with “Elysian” as descriptors; and five with “Beverly,” hinting at some sisterhood with Bev Hills, whose own pre-incorporation name was for a ranch called Morocco Junction.

Most boldly, in 2003, the L.A. City Council dumped the name “South Central Los Angeles” — a name it believed unjustly besmirched the neighborhood — in favor of “South Los Angeles.” That vast part of L.A. below downtown already has plenty of older neighborhood names to use: Vermont Square, more than a century old, with a historic library; Green Meadows, Canterbury Knolls, Corinth Heights, Chesterfield Square. Some residents would like names of more current character: Africa Town, say, or Little Africa, and why not Wakanda?

Poaching remains bad renaming etiquette. I’ve thundered for years about the identity theft by Los Feliz and Silver Lake hipsters who call themselves Eastsiders. Well, yes, they’re east of Westwood, but Los Angeles’ authentic Eastside identity belongs to the original, largely Latino neighborhoods east of the L.A. River as it courses near downtown. Want to be a true Eastsider? Move there.

It remains a mystery why there is no designated “South Hollywood.” How can that not be a real estate marketer’s dream?

And it’s a heartbreak that Edendale, one part of town unquestionably deserving of blue-sign status, has been virtually rubbed off the map. Edendale is legendary in film history, the Echo Park-adjacent neighborhood that was making movies before a single Hollywood studio opened for business. Yet it’s been divvied up like Gaul among other neighborhoods, and Allesandro Street, the golden mile of L.A.’s first film studios, has been chopped up and abused as the “Glendale corridor.”

How about it, L.A.? Everybody sing: “Hooray for Edendale!”

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.