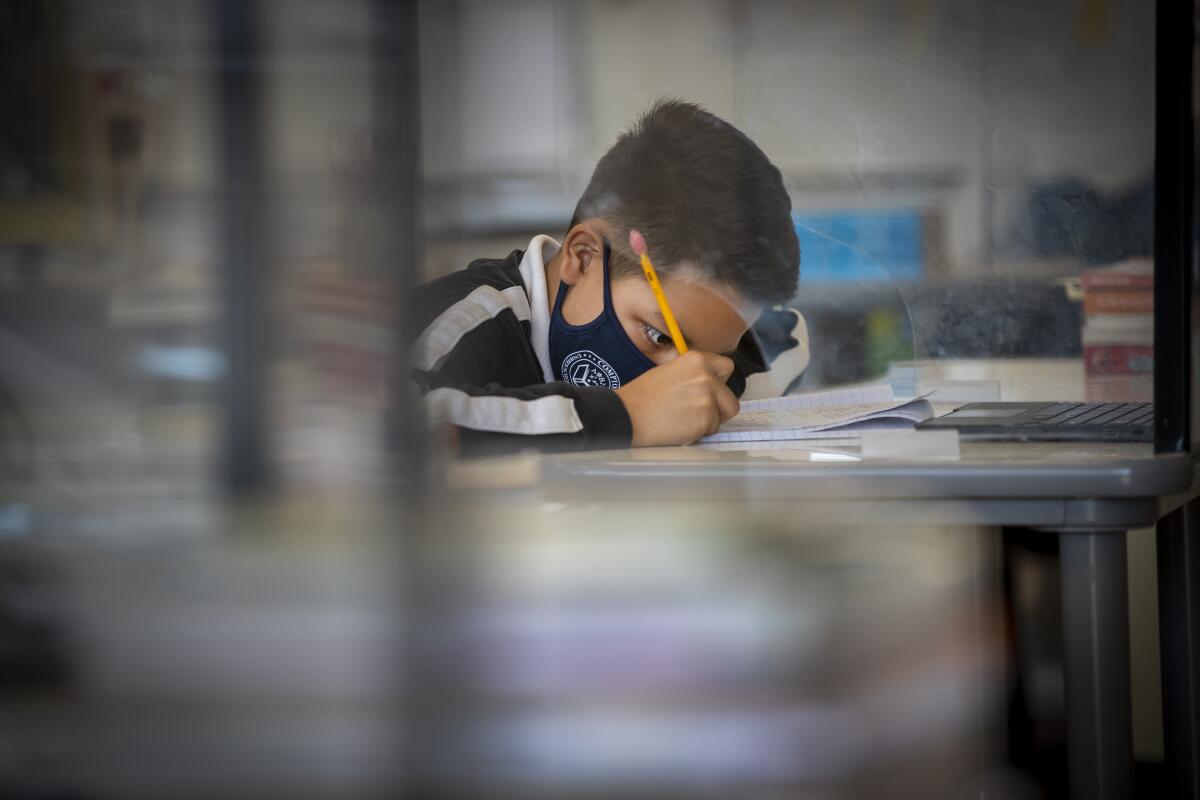

Parents say their children have been ‘substantially hurt’ by school closures, survey finds

Los Angeles County residents rate education among the worst of several factors affecting their quality of life, displaying one of the biggest drops in recent years among parents of children in public schools, according to a UCLA survey.

More than three-quarters of parents in the county with children ages 5 to 18 believe their children have been “substantially hurt” academically or socially by being away from school and taking part in distance learning for months.

“It’s a big number,” said Zev Yaroslavsky, director of the Los Angeles Initiative at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs, which publishes an annual Quality of Life index in partnership with the public-opinion firm FM3 Research. “It’s not counterintuitive; it’s intuitive, but the number surprised most of us — and it was across all the demographics.”

The Quality of Life index is a composite score on a scale of 10 to 100 that reflects how satisfied people are in nine categories and the weight they assign to each category. The overall score this year remained relatively steady, at 58 — meaning residents rated their overall quality of life slightly more positively than negatively — but there were notable shifts within the categories and differences by subgroups.

For example, parents of children in public schools gave education an overall score of 52, compared with 58 last year, one of the largest decreases in any category in the index’s six-year history. In large part, the change reflected dissatisfaction with the quality of K-12 education and training for “jobs of the future.”

But strong majorities of parents approved of their own public school district’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“While the parents think their kids have been substantially hurt by distance learning, they don’t necessarily blame their school district,” Yaroslavsky said. “The people who have stakes in the system have a much more empathetic or tolerant rating of the school districts.”

Some 1.1 million students in California are English learners. Experts say schools must make immediate and swift interventions to salvage their education.

The index also put into stark relief inequities by income. The overall Quality of Life index came in at 49 for people who said their income dropped by “a lot” in the last year, a group that represented 22% of the sample. The score for the 56% of respondents who said their income stayed the same or went up was 62.

Detailed findings from the survey showed that the group that lost significant income experienced compounding effects from the pandemic, said Adam Sonenshein, a vice president at FM3. They were more likely to know somebody who had tested positive for the coronavirus, to say their kids were negatively affected by distance learning and to say the response to the pandemic was unfair to people like them. They were also less likely to have been vaccinated, to have a favorable opinion of government officials and to agree with the statement that L.A. “is a place where people who work hard and dream big can get ahead.”

“The pandemic has exposed the two L.A.s again,” Yaroslavsky said. “There’s one … portion of our region that was really hard-hit, had significant impacts on their income, on their jobs, on their kids in school, possibly on their health — and then you’ve got the rest of L.A., which did not get hit hard in an existential way. Those are two different worlds.”

Rosaura Andrade of North Hills exemplifies the first group. A single mother of two who works as a baby-sitter outside her home, Andrade lost work and pay during the initial months of the pandemic, causing her to rely on food banks and to fall five months behind in rent.

Once back to work full time, she struggled to support her children with distance learning. While at work, she would get calls from their teachers saying they weren’t in class. When she called home to ask her kids, they would say they lost track of time or got distracted with the television.

“I felt powerless — I have to work,” she said. “Many mothers have left work, but I don’t have that option…. The choice is, do I stay with my children, or do I feed them?”

Andrade’s son, who began high school in the fall as a strong student, ended up failing English and biology, in part because he didn’t know his teachers well and was too embarrassed to ask for help, she said. Her daughter, a very social fifth-grader, has expressed suicidal thoughts. Andrade has had both of them in therapy for a year.

She said she understood the difficulties teachers and schools faced with remote instruction, but “they needed to do more — I just don’t know who or what.”

Ada Mendoza, a West Athens parent of four school-age children, including one with learning disabilities, is a stay-at-home mom whose husband works in construction. The pandemic and remote learning took a toll on their family, too.

Mendoza, who doesn’t speak English and never learned to use a computer or typewriter, struggled to help her kids log on to their online classrooms. Her high schooler studies from a bedroom, while her two youngest split the table in the dining room, where they get bored and are easily distracted. She works one-on-one with her son who’s in special education.

“They’re still earning good grades, but I feel their learning has dropped a lot,” she said.

The entire family fell ill with COVID-19 in December, and Mendoza is wary of sending her kids back to campuses, where they could be exposed again.

“I don’t know what the situation will be next year,” she said. “They’re tired, and so am I.”

Beyond education, the survey showed, as it has in previous years, notable dissatisfaction among young people with the cost of living in L.A., particularly the cost of housing.

And although Latinos have faced greater hardship from the pandemic and recession, it was young white residents who expressed less optimism about their economic well-being and greater disapproval of government officials. Among white residents ages 18 to 49, 38% reported participating in a protest in the last year.

“Among younger white residents in Los Angeles County, a greater sense of frustration and even bitterness is apparent,” Paul Maslin, a partner at FM3, said in a news release.

UCLA and FM3 surveyed a random sample of 1,434 L.A. County residents over the phone and online during a 20-day period in March. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish, and the data were weighted to represent county demographics.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.