The siblings and their mother gathered in a circle around the family table.

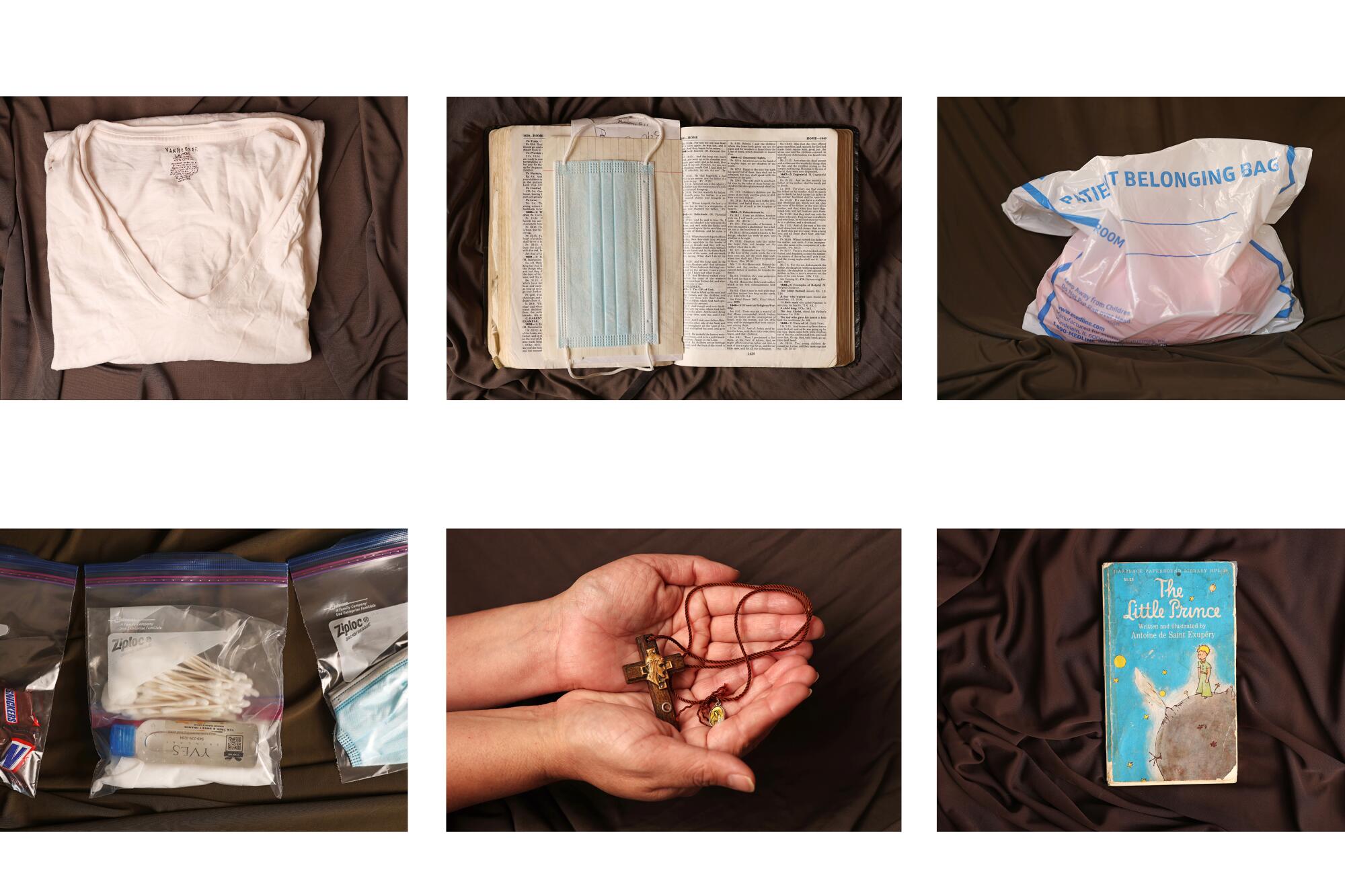

One by one, they pulled items from the plastic bag they’d picked up from the hospital lobby. Their mother went first, selecting her husband’s reading glasses, devotional booklets and Bible, a reminder of their nightly routine of reading the word of God together.

The eldest daughter selected a shirt her father had worn in the hospital, as well as his cellphone, and two other sisters picked their father’s Virgen de Guadalupe prayer card and a rosary purchased on a trip to Israel. Their brother chose a ring, a nephew a pair of sweatpants and someone else the snow globe recently purchased at the hospital gift shop.

When it was her turn, Lupe Torres picked twin wooden crosses her father often wore around his neck.

Not long before, all the items had been inside her father’s room at Foothill Presbyterian Hospital, where he had been admitted two months earlier with severe complications from COVID-19.

Doctors put him on high-flow oxygen and he slowly regained strength, but progress zigzagged. Shortly before Torres’ father was intubated, he spoke to his son on the phone, managing a single word.

“Bye.”

He died Jan. 15, two weeks before his 71st birthday.

In normal times, when families can be at bedside as a loved one draws a final breath, relatives box up their belongings on their own. But nothing was normal in January — during the deadliest surge in Southern California, then the nation’s hotbed of infection — and hospital staff scrambled to prepare the room for the next patient.

Her father died early in the morning, Torres said, and when she arrived at the hospital lobby a couple of hours later, his belongings had already been bagged up. She later noticed that only a single gray sneaker from the pair he was wearing when admitted had been returned. It felt like an assembly line, she said, as if, in that moment, her father was just a number.

“Just another person who died of COVID,” she said somberly.

These days, she starts every morning by kissing a photo of her father, replaying memories of dancing and laughing and eating sopa de elote together at the holidays. She remembers Christmases past and how, just before midnight, her family prayed together and her father made a point of telling every relative how much he loved them.

Before the pandemic, hospitals asked relatives to take their loved ones’ final items home with them, and in cases when a patient died alone, most facilities stored valuables in a safe until someone could pick them up.

But as the virus spread, nurses also acted as death doulas and tech support on Zoom calls, as well as helping handle patients’ belongings, which they knew could be precious to family members.

“Any little thing can mean so much,” said Valerie Ewald, an intensive care nurse at UCLA Santa Monica Medical Center, who added that, after her father died a few years ago, she kept her visitor’s pass from the hospital.

Fewer items have been allowed into patient rooms during the pandemic, said Ewald, who noted she was speaking in her capacity as a union member of the California Nurses Assn. But nurses, she said, have done what they can to safely retrieve belongings from the rooms of COVID-19 patients, including using a UV light machine that sterilizes N95 masks to clean cards and a poster board so family members could display them at a memorial.

“Memories are so important,” Ewald said, “and memories are tied to items.”

Early in the pandemic, Christine Ligoretti did what she could to help her mother from afar.

From her home in Aliso Viejo, she pleaded with her mother to turn down dinner invites, had pizza and wings delivered to her apartment in upstate New York and bought her a Dell desktop, which she used to watch the nightly news hosted by David Muir, whom she adored.

When her mother was hospitalized with pneumonia in October, Ligoretti checked in frequently, a habit she continued when her mother returned to the hospital two weeks later, now testing positive for the coronavirus.

Doctors assured her it wasn’t yet time to panic, but she decided to ship her mother’s Christmas present early: a new Bible and crucifix, playing cards, copies of a dog magazine she enjoyed, snack-sized Snickers bars and Cetaphil, her mother’s favorite lotion.

Then, one morning, a doctor called with results of her mother’s CT scan. “Her lungs are completely shredded,” he told her. They didn’t have much time left, Ligoretti knew, and the box with the Bible inside still had not arrived.

Her sister, who had been allowed into the hospital room, picked up her mother’s old Bible, and Ligoretti watched via video call as her mother tried to thumb through the pages, her hands shaking. Ligoretti snapped screenshots as her sister read aloud from Psalm 23: “The Lord is my shepherd….”

Dianne Sweeney died two days after Thanksgiving. She was 75.

Knowing that the box had been so close but never made it to her mother crushes Ligoretti. After relatives mailed it back to her, she realized some items had been added — tender, unopened letters that friends had sent to her mother in the hospital.

She wept as she read them, just as she does these days when she rereads old text exchanges or listens to a now-cherished voicemail of her mother asking for help getting her computer set up to watch Muir on the news.

“Hi, honey,” it begins. “It’s just me.”

::

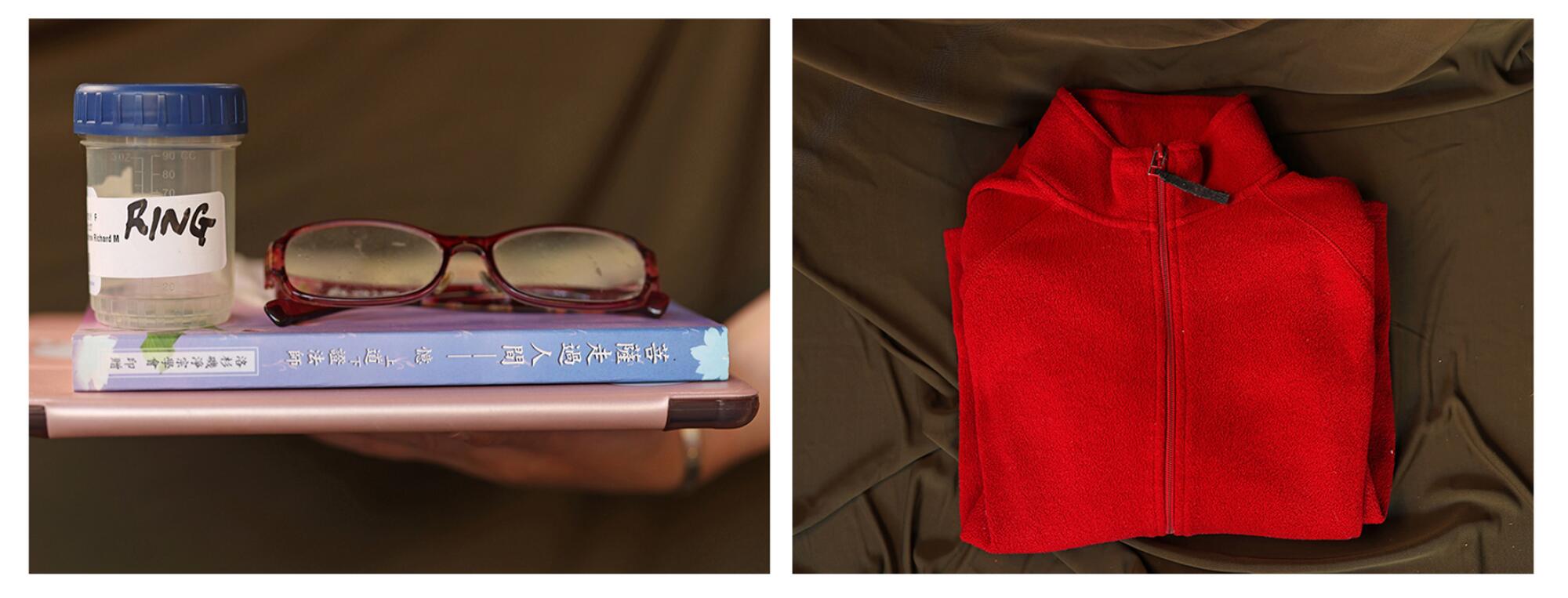

Last fall, about a month before Nancy Chen’s mother died, around the time she was intubated, doctors granted Chen and her sister an end-of-life visit.

Her mother’s condition had steadily deteriorated, and eventually she became septic.

Earlier in the pandemic, Chen and her sister had been cautious, visiting their mother only from the driveway of her San Gabriel Valley home. Chen sometimes felt angry with her mother, who had still been meeting up with friends, although, after some contact tracing, Chen deduced that her mother must have gotten sick from a tenant with whom she shared common areas.

Kuei Ching Chen was 70 when she died in the hospital.

While there for the end-of-life visit, Chen gathered some of her mother’s belongings, including her purse. When she later looked inside, she found sacred bracelets and writings, reminders of her mother’s Buddhist faith, as well as bread rolls tucked inside crumpled napkins with small, foil-wrapped rectangles of butter.

In the final days before she was intubated, Chen realized, her mother, a vegetarian, must have taken the rolls from her dinner plate and stashed them away for days when the meals didn’t fit within her dietary restrictions or sound appetizing.

Thinking about those hidden rolls still makes her sob — she imagines that her mother, a native of Taiwan who spoke English as a second language, must have felt so terrified and alone in her hospital bed.

These days, when she misses her mother, Chen looks down at the red zip-up sweatshirt she wore when she felt cold, which was often. Her mother had worn it in the hospital, and if not for that, Chen said, she never would’ve washed it.

She also finds comfort in keeping her mother’s cellphone number active, noting that her siblings plan to do the same thing they did after her father’s death in 2018: pass the number along to one of the grandchildren. They’ve also kept the family’s landline — the number they got soon after emigrating from Taipei in the early 1980s.

::

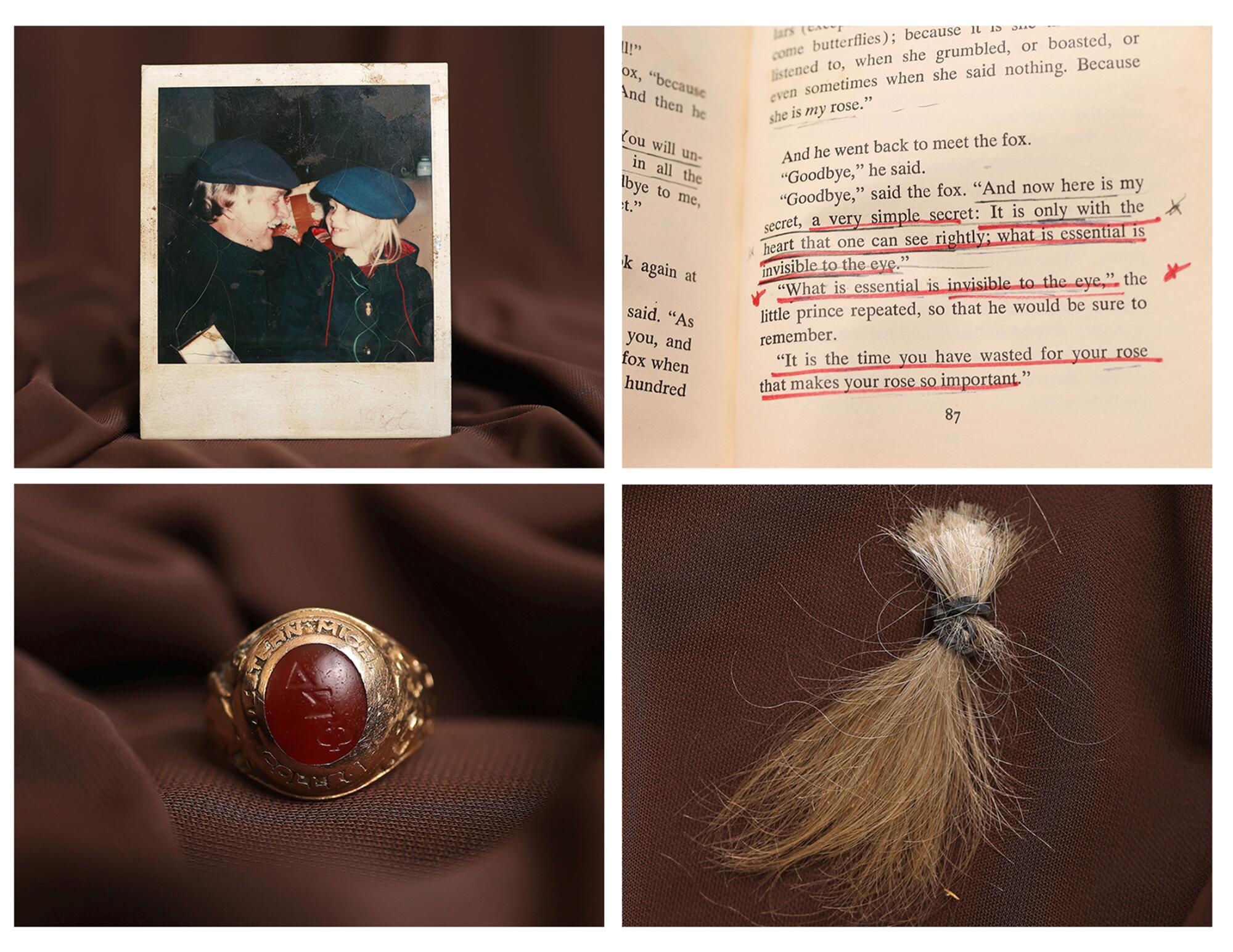

Shane Leigh fixated on the outfit her father would wear in his casket.

He’d been voted best dressed at his Arkansas high school in the 1940s, and years later, when he was working in Hollywood and eventually married to Rudy Vallée’s widow, Eleanor, he had loved to piece together a sharp ensemble before a party.

She considered a three-piece cashmere suit with cuff links but decided on a far simpler outfit, one she remembered him wearing when she was a little girl: a pair of Wranglers and a denim shirt with a tweed sports coat.

She tucked an old postcard — one she’d mailed to him from France years earlier — into the inside pocket of his coat, knowing it would rest over his heart forever. The card included a line in French from “The Little Prince,” which he’d often read to her as a child:

It is only with the heart that one can see rightly. What is essential is invisible to the eye.

Leigh, who asked to be identified by her first and middle names for privacy, then headed to Forest Lawn in the Hollywood Hills, dropping off her father’s outfit and retrieving a small lock of his straight, ash-colored hair.

She asked the mortician to leave her father’s wedding ring on — so his wife wouldn’t be mad when they were reunited, she said — but took home his beloved college ring. The gold band inscribed with “Western Michigan University” was a reminder of the time he’d spent studying under a renowned speech therapist, ultimately overcoming his stutter, which paved the way for a career as a voice actor.

Leigh started crying the moment she saw the ring off her father’s hand, she said, feeling more finality in that instant than when she watched his casket lowered into the earth. She wore it on a chain around her neck for a week, then stored it away, planning to one day give it to her son, Sam, who is now 10.

In the first 72 hours after her father died, linear time felt warped, she said, and she was transported back to happy childhood memories. She thought of newer, more strained memories too — of their fights about COVID.

If he wasn’t careful, she’d warned him, he could end up alone in a hospital room with a tube down his throat. Her father, who’d become a zealous Fox News watcher, brushed off her concerns with a colorful expletive, insisting on running errands on his own.

Byron Clark died on the seventh day of the new year. He was 94.

To have said goodbye over Zoom instead of from his bedside, Leigh said, felt like being robbed of something essentially human. She remembers staring into the screen at her father, whose eyes were barely open. Do you think he can hear me, she asked?

“I hope so,” a nurse answered.

As her father took his final breath, she watched the nurse stroke his hair though a glove.

Because of COVID-19 restrictions, only Leigh and Sam had attended the burial. They sang “Amazing Grace” and she read a passage from her old copy of “The Little Prince.” She had considered placing it in the casket, before realizing she needed it more.

::

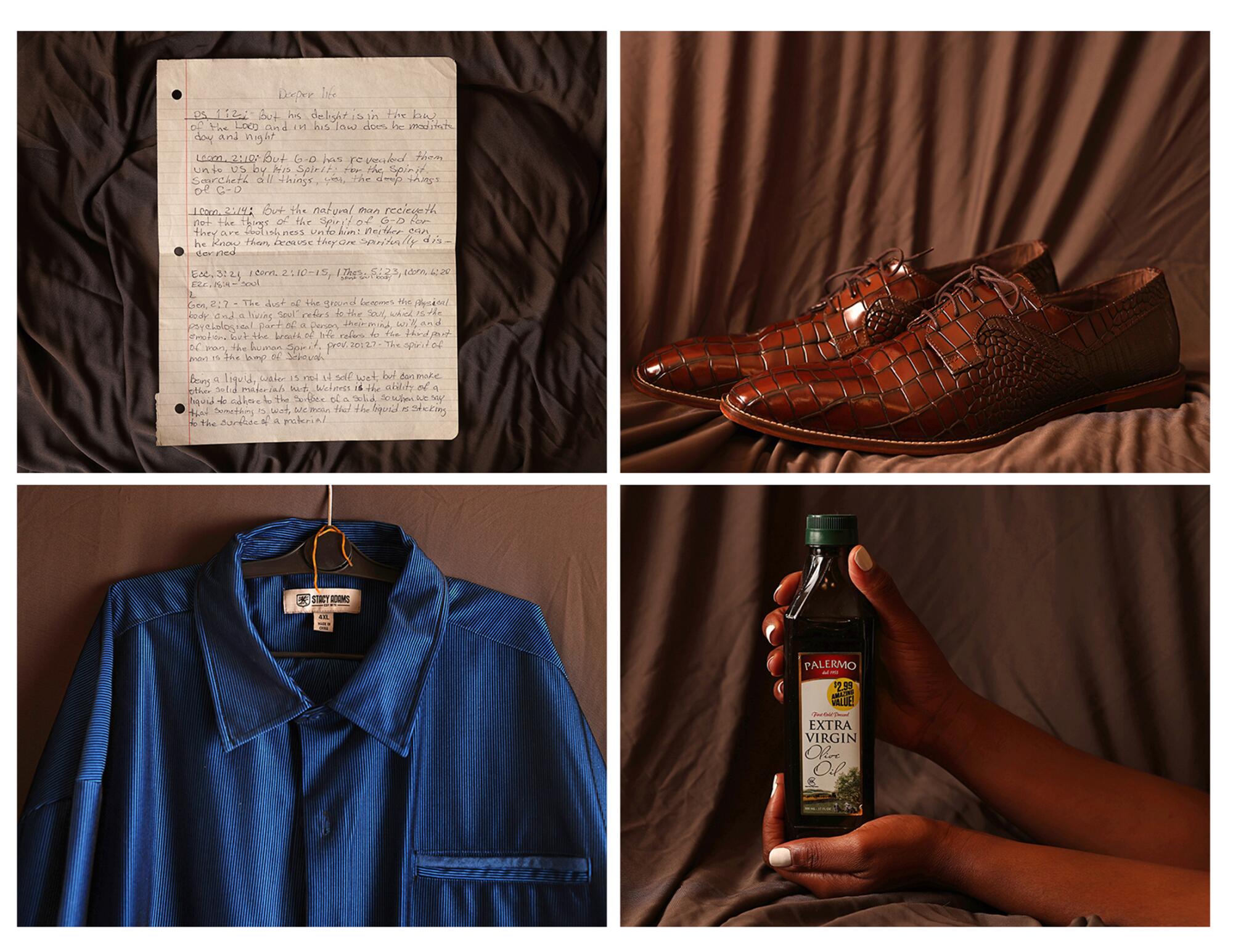

Shané Bundy looked through the glass at the hospital bed.

Her father had died minutes earlier, doctors told her, but he looked as if he was sleeping. Outside the room was a bag of her father’s belongings — his worn Bible, a bottle of blessed olive oil, letters from loved ones and earbuds, which made it easier for him to FaceTime with loved ones over the sound of his oxygen supply.

“He’s not coming home with his things,” Bundy remembers thinking. “We put so much value in material things, but it doesn’t go with you when you leave.”

Bundy felt numb and exhausted. She’d recently recovered from COVID-19 herself, as had her father’s wife — her “bonus mom,” she calls her, or just Mom — who was hospitalized at the same time as Bundy’s father. They all got sick in November, after a short getaway to Las Vegas.

Bundy was the first to feel symptoms, mainly a small headache, but soon her mom had a cough and eventually her father did, too. He lost his appetite, and about a week later she found him slumped on the edge of his bed.

“Daddy, are you OK?”

“I’m not.”

He was admitted into the hospital but hated being there without family by his side and had concerns about his care. He checked himself out, Bundy said, and went home with portable oxygen. Hours later, he was back in the hospital, texting his daughter updates on his condition and constantly reminding her that he loved her.

Her father, Gregory Bundy Sr., died two days before Thanksgiving. He was 64.

Now, when she sees his clothing around the home they shared in Moreno Valley, she flashes back to family meals at BJ’s or Olive Garden after church on Sundays, to watching him worship while wearing a certain suit.

She thinks of all the people who loved her father, who was the assistant pastor at the Greater Page Temple Church of God in Christ in South L.A. She thinks about the steadfastness of his faith in Jesus Christ — how he waited until marriage to consummate his relationship with his second wife and how he always kept his cool in traffic, never cursing back at anyone.

“He walked what he talked.”

She hadn’t kept any voicemails from him, which now devastates her, so when she wants to hear his voice, she listens to recordings of his old sermons or pulls up a video she made capturing his voicemail greeting.

“Praise the Lord, you’ve reached the Bundys’ residence,” he says, his voice booming.

She sometimes listens to the recording, often twice in a row, and sobs.

::

When he first arrived at the hospital, Jennifer Lloyd’s father didn’t have anything with him.

He’d been transported by ambulance after police broke into his Washington, D.C., home during a welfare check and found him disoriented. Lloyd knew her father had been cautious during the pandemic, almost never leaving the house, but as she and her wife got ready to fly east from Sacramento, an emergency room doctor called saying he’d tested positive for the coronavirus.

Lloyd went to her father’s rowhouse and gathered some items to drop off for him at the hospital — his cellphone, wallet, hairbrush, toothbrush and a set of pajamas. She wasn’t allowed past the lobby at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, but at least he now had his cellphone.

“Good Morning,” she texted him a few days later. “How is it going?”

“Not so good. Had a rough night.”

Her 76-year-old father, who had lung cancer several years earlier, didn’t want to be put on a ventilator, and when his condition worsened, family and friends gathered on Zoom to say goodbye.

Alexander “Lenny” Lloyd died May 6 — one of the first 100 COVID-19 victims to die in the nation’s capital.

When she picked up his belongings the next day, hospital staffers told her to spray everything with Lysol, but she couldn’t handle the thought of destroying any lingering scent. A few days later, she went into the basement of her father’s home by herself and opened the bag. She took a deep breath, inhaling his Aqua Velva aftershave.

Another item she picked up from the hospital — her father’s cellphone, which she has kept active — feels like a lifeline. She still sends him texts from time to time:

“I hope I kissed you enough!!!”

“your obituary posted.”

“This is so unfair that I never get to see you again.”

She still has three of his old voicemails — one checking about fires in California, another saying he needed help with his Lyft account and a third wishing her a happy birthday.

“Give me a call please,” he tells her. “Thanks, bye.”

Now, when she misses him most, she listens to the recordings, grateful for the tangibility of his voice floating into her ear.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.