A tale of FBI trickery, organized crime, fake phones and millions of spilled secrets

The full extent of an unprecedented FBI effort to beat the criminal underworld at its own encrypted-communications game became clearer Tuesday following a two-day takedown, with some 800 arrests worldwide and San Diego racketeering indictments against 17 high-level targets, according to federal authorities.

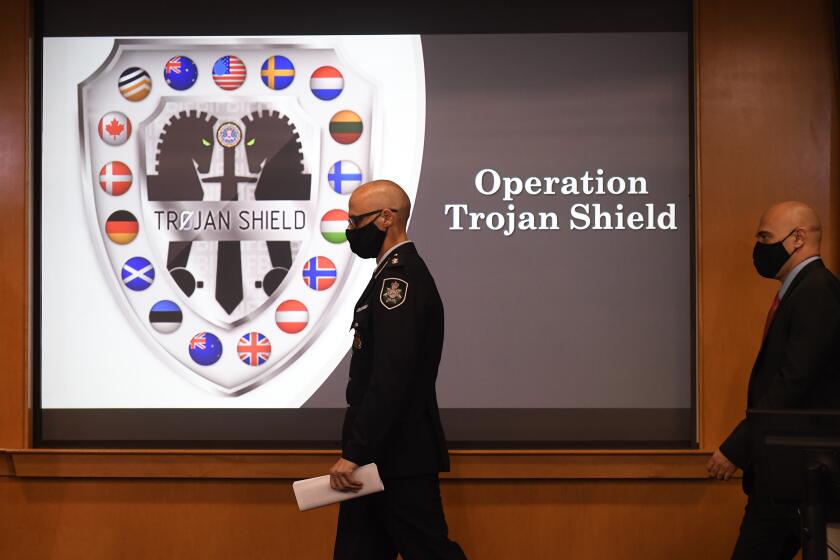

Dubbed Operation Trojan Shield, the effort was largely led by FBI agents and federal prosecutors in San Diego who covertly created a closed-loop encryption cellphone service, called ANØM, and then relied on trusted voices already embedded in criminal syndicates to distribute the customized phones.

The agents secretly read each message that poured in — 27 million in all. They read about shipments of cocaine stamped with Batman logos, cocaine hidden in tuna cans headed to Belgium, cocaine sent in French diplomatic pouches, and cocaine in refrigerated fish destined for Spain, according to a search warrant unsealed this week.

There was talk of planned murders, evidence of corrupt law-enforcement officers and a rare behind-the-scenes glimpse of crime bosses conducting their own profitable side deals, officials said.

The messages that were secretly being funneled to investigators over an 18-month period were brazenly unfiltered in detail and breadth, recording every movement of some 300 organized crime groups operating in more than 100 countries, said Suzanne Turner, FBI special agent in charge of the San Diego field office.

“The amount of intelligence we received was staggering,” Turner said at a news conference Tuesday.

Criminal gangs used what they thought was a secure messaging app, but it turned out that the FBI and other authorities were privy to every word.

Intelligence was then turned over to the appropriate authorities in cooperating countries. As a result, she said, several drug shipments were intercepted and murders likely thwarted.

The culmination of the operation was announced the previous day by partner agencies in Australia, New Zealand and Europe, where the vast majority of ANØM users — biker gangs as well as Italian mafia cells — were targeted for arrest on various criminal charges. In the last few days, about 500 people have been arrested, adding to 300 arrests made during the course of the investigation.

Six law enforcement officers were arrested abroad on corruption-related charges, and dozens of other public officials remain under investigation, Turner said.

No one was arrested in the United States. Seventeen foreign nationals have been indicted, however, on U.S. racketeering charges for alleged roles of aiding and enriching criminal organizations by administering or distributing the ANØM cellphones.

Eight defendants were arrested in other countries, and nine remain fugitives. They will eventually be extradited to San Diego.

The case stemmed from a series of related investigations based in San Diego, starting with the undercover infiltration of Owen Hanson’s international sports-betting and drug-trafficking organization.

Hanson’s organization depended on encrypted communications hosted by Phantom Secure, a company based in Canada. When a joint effort by the FBI, Canada and Australia took down that service, it created a void for Phantom Secure’s 10,000 customers.

Exactly how the FBI took the investigation to the next level is detailed in a search warrant affidavit unsealed late Monday.

During the investigation, agents were able to recruit a confidential source who had previously distributed phones for Phantom Secure and was developing the next-generation encryption device, according to the search warrant. Like most devices before it, the phone was stripped of all other capabilities and connectivity and used only to send messages to others on the same platform.

The source — who has a previous drug-importation conviction and was facing charges in connection with the Phantom Secure case — agreed to offer his new phone to agents for the massive sting, as well as distribute the product to contacts within criminal organizations, the warrant says. He was paid $120,000 by the FBI for his services and another $59,500 in travel and living expenses.

But the device needed major tweaks.

The Australian Federal Police helped build a master key into the existing encryption system so that each message could be secretly decrypted and stored by law enforcement as it was transmitted.

A virtual perimeter, or geofence, was put up around the United States so messages could not be collected from ANØM devices located in the United States, according to the search warrant — a safeguard apparently meant to protect the constitutional rights of U.S. citizens. The 4th Amendment prohibits the government from indiscriminately eavesdropping on the electronic communications of U.S. citizens without a probable-cause search warrant.

Instead, the operation was designed to collect information from foreigners using the devices abroad, per an “international cooperation agreement,” according to the U.S. attorney’s office.

Assistant U.S. Atty. David Leshner declined to discuss on Tuesday the specifics of the U.S. and foreign legal authorities used for the operation.

“It was a lawful operation,” he said, “and our foreign partners complied with their own legal requirements.”

ANØM started off with a small-batch test run in Australia in October 2018, using three former Phantom Secure distributors to get the phones into the hands of criminal groups. Australia’s initial judicial order for the intercepts did not allow sharing with foreign partners, and the FBI was only made aware of the general nature of the messages.

But the experiment worked and was greenlighted for expansion.

The FBI didn’t begin collecting and reading messages until October 2019, when an unidentified cooperating country obtained legal permission to route the messages through a particular server. The country then regularly sent the latest batches of messages to the FBI to read and analyze. Any messages that appeared to come from within the U.S. were reviewed by the Australian Federal Police only for threats to life, according to the warrant.

The subsequent takedown of another encrypted platform, Encrochat, by European authorities in 2020 pushed more customers through word-of-mouth to ANØM.

Demand for ANØM boosted again after the San Diego FBI and partner countries dismantled yet another encrypted platform, Sky Global, in March. The Canadian-based CEO is being prosecuted in San Diego.

Over time, the FBI covertly built a distribution network of trusted experts in encryption security who marketed ANØM as “designed by criminals, for criminals,” helping build up the appearance of legitimacy, prosecutors said. That network is now facing charges in San Diego.

News Alerts

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Three men — Joseph Hakan Ayik of Turkey, Domenico Catanzariti of Australia, and Maximilian Rivkin, a Swedish citizen living in Turkey — are accused of working as administrators for ANØM. The FBI allowed them to take control of customer service functions, initiating new accounts, setting up access for distributors and wiping devices clean when the device was believed to have been compromised by law enforcement, according to the indictment.

Ayik is a well-known figure in Australia — dubbed the “Facebook gangster” by media — who openly flashed his illicit wealth before fleeing the country following a heroin-trafficking investigation, according to news reports. He and Rivkin are still at large, while Catanzariti is in custody.

Fourteen others — from across Europe, Colombia, Thailand and elsewhere — are charged as distributors.

In all, some 12,000 ANØM phones were sold, costing $1,200 to $1,800 per six-month contract, depending on the part of the world, court records state.

“Every single person who used ANØM used it for a criminal purpose,” said Acting U.S. Atty. Randy Grossman.

The countries with the most users were identified as Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Australia and Serbia.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.