17 million gallons of sewage discharged from Hyperion treatment plant, closing some beaches to swimming

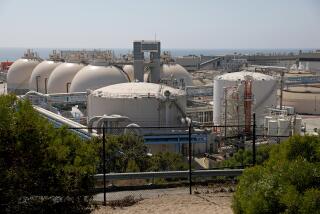

Debris flows overwhelmed the Hyperion sewage treatment plant in Playa del Rey on Sunday afternoon, forcing officials to use an emergency measure to discharge 17 million gallons of sewage through a pipe one mile offshore.

Timeyin Dafeta, the executive plant manager at the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant, the city’s oldest and largest wastewater treatment facility, said in a statement Monday that about 17 million gallons of sewage — or 6% of a daily load — was discharged one mile offshore instead of the typical five miles to prevent the plant from discharging much more raw sewage.

Dafeta said he believes that the incident was the largest amount of untreated sewage discharged through the one-mile pipe over the last 10 years. Water flows were directed back through the normal treatment process Monday morning, and officials are investigating the cause of the debris and repairing damaged equipment.

“At this time, all flow is being treated through its standard treatment processes,” Dafeta said.

The L.A. County Department of Public Health issued an advisory Monday urging residents to avoid swimming in areas around Dockweiler State Beach and El Segundo Beach. It said that water quality samples were collected Monday morning to look for elevated amounts of bacteria, with results expected within 24 hours.

At about noon on Sunday, a large amount of debris unexpectedly clogged filtering screens with openings less than an inch in size at the treatment plant, said Barbara Romero, the director of L.A.’s Department of Sanitation and Environment.

The plant’s managers tried adding screens to replace the ones that were blocked. They also tried redirecting the flows to a storm drain system within the plant — an alternative way to bring the water through the normal treatment process.

But after several hours of recirculating the water, the system was still too overwhelmed.

“The flow wasn’t subsiding enough to get it through the treatment process,” Romero said. “Out of the 260 [million gallons] that comes in, we ended up with 17 [million] that couldn’t go through the treatment process.”

So about 7:30 p.m., plant workers discharged the wastewater one mile out and 50 feet deep into the ocean. The normal process directs treated wastewater 190 feet down.

At 4:30 a.m., workers successfully used a recently installed channel to route the flows of water back through the standard treatment process, said Romero.

The one-mile pipe was last used for a major discharge of wastewater in 2015, Dafeta said.

The plant then used the one-mile pipe for an emergency during a rainstorm, Dafeta said. But the flow also expelled trash that had been lying dormant within the pipe for years, forcing the closure of Dockweiler Beach. Later that year, he said, the plant received authorization from the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Board to use the pipe during repairs of the five-mile pipe.

Deep sea explorers are stunned when they investigate a mysterious dumpsite for DDT waste barrels off the coast of Los Angeles

Dafeta said officials are unsure what led to the large amount of debris that triggered use of the one-mile pipe Sunday but that the amount of wastewater that had flowed into the ocean was mitigated because of improvements made after 2015.

“Why that quantity and where it came from is what we’re still trying to ascertain at this point,” Dafeta said. “It’s the amount of material and the kind of materials that came through that caused the problem for the screens.”

In a statement, L.A. County Supervisor Janice Hahn said that she understood that the plant was able to prevent an even larger spill but that “we are going to need answers about how and why this happened.”

The environmental group Heal the Bay said in a statement that while debris such as tampons and plastic trash, when released into the ocean, can harbor bacteria and entangle wildlife, “it seems in this case those debris were successfully filtered out of the spill before it made it to the Bay.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.