Many California farmers have water cut off, but a lucky few are immune to drought rules

- Share via

KNIGHTS LANDING, Calif. — Driving between her northern Central Valley rice fields with the family dog in tow, fifth-generation farmer Kim Gallagher points out the window to shorebirds, egrets and avocets fluttering across a thousand-acre sea of green flooded in six inches of water.

“People say agriculture uses so much water, but if you knew who lived in these areas and if you saw the animals taking advantage of it, you’d think there’s a lot more going on here,” Gallagher said. “This is where you’re going to find a Great Blue Heron. If you don’t want that type of bird then we shouldn’t be growing rice.”

The nearly 500,000 acres of sushi rice grown in the Sacramento Valley each year serve as the wetland habitat for thousands of migrating birds along the Pacific Coast. Yet the crop also uses more water than most, and about half of the product is exported to countries including Japan and South Korea.

Since the 1920s, farmers have grown rice in the Sacramento Valley, where old hands fly crop duster planes and rice emblems mark the county buildings. Now, due to decades-old agreements with the federal government, rice farmers like Gallagher are going relatively unscathed by unprecedented emergency water cuts to farmers this month as others fallow fields, wells go dry and low water levels imperil Chinook salmon, the native cold-water fish that play critical ecological roles and support a billion-dollar fishing industry.

A handful of districts supplying farmers including Gallagher are receiving nearly 2 million acre feet of water this drought year, enough to supply the city of Los Angeles for roughly four years. Their seniority is a function of the state’s complicated water rights system, which some experts say is ripe for reform as extreme drought magnifies the inequities within it.

Developed in the 19th century by miners who used water to blast gold out of the Sierra foothills, California water rights are based on a concept known as “first in time, first in right.”

The principle, which remains central to state water law today, roughly translates to “first come, first served” to a quantity of water from a natural source. During drought, rights are curtailed by state regulators from newest to oldest to protect water for residential use and human health and safety essentials.

Most farmers across the state who rely on the Central Valley Project, the nearly two dozen dams and hundreds of canals that make up the federal water allocation system, are getting 5% or less of their usual water supply this year.

The state water board’s most recent emergency order barred thousands of farmers, landowners and others from diverting water from the massive Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta watershed that stretches from Fresno to the Oregon border, forcing many to turn to groundwater pumping.

Some of them with rights claims predating 1914, the year California enacted its water rights law, say the State Water Resources Control Board lacks authority to curtail them and sued over the issue during the last punishing drought.

Meanwhile, districts like Gallagher’s that have contracts with the water project based on those rights, called the Sacramento and San Joaquin River Settlement Contractors, have never been cut off by more than 25% — even in the driest years.

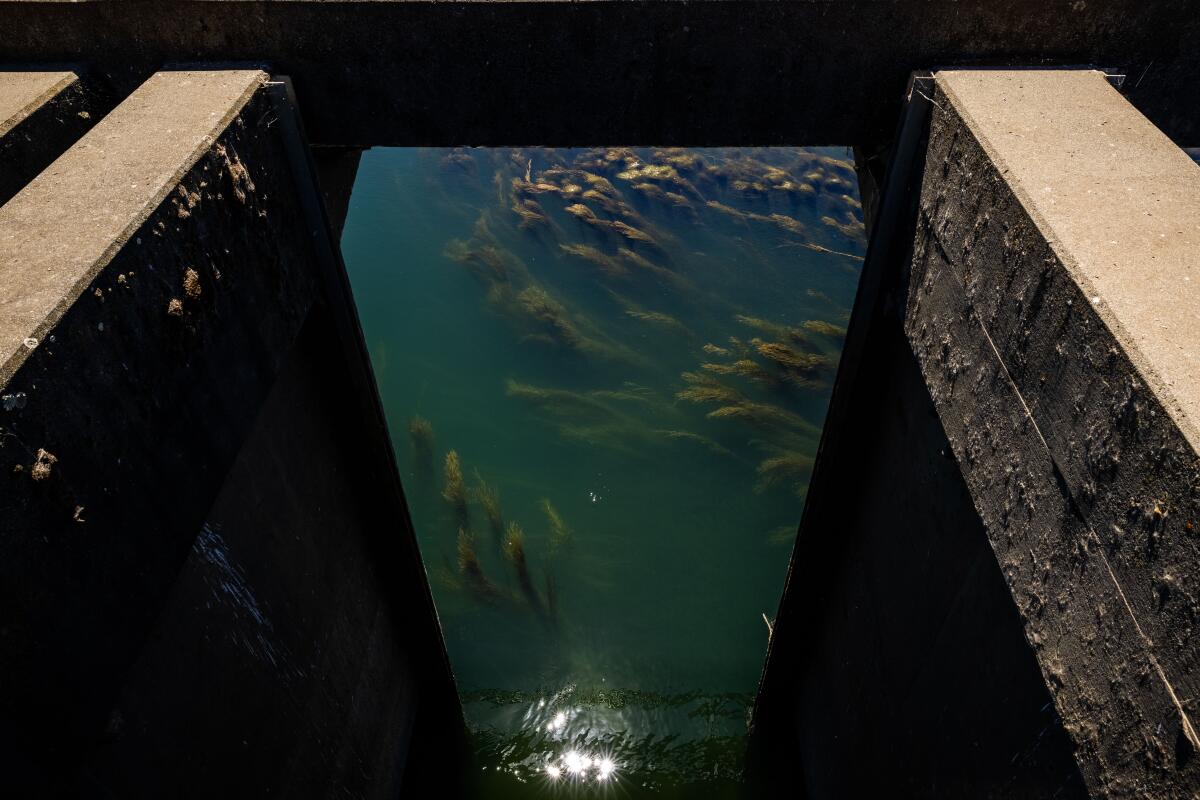

The largest of this group is Glenn-Colusa Irrigation District, 260 square miles of land best known for rice growing. Its multistory pump station sits on a bend in the Sacramento River near where, in 1883, future state legislator Will S. Green nailed a paper notice to an oak tree claiming millions of gallons per minute of the river’s natural flow.

When the federal government was building the Central Valley Project in the 1940s, irrigators such as Glenn-Colusa sued, settling after nearly 20 years of negotiations for contracts to stored water from Shasta Lake, the state’s largest man-made reservoir.

Regardless of conditions, federal officials operating Shasta Dam are now obliged to fulfill those contracts to rice farmers and others along the San Joaquin River, with the expectation that there will be legal action if they don’t.

‘An unprecedented year’

Built by the federal government in the 1940s in the wake of the Great Depression, Shasta Lake is the cornerstone of the Central Valley Project.

The dam is operated by the federal Bureau of Reclamation, which is responsible for distributing water to farms and communities while protecting the watershed’s fish and wildlife. Although the two obligations are equal in the eyes of the law, they often conflict when there’s not enough water to go around.

Over the years, the impact of the perennial tug-of-war between competing interests has been felt in the increasing die-off of Chinook salmon, one of California’s most iconic fish species.

In April, just as rice farmers in the Sacramento Valley received water to flood their fields, record evaporation of snowpack on the Sierra Nevada mountains meant some 800,000 acre feet of water didn’t melt into reservoirs as expected.

Soon after, the State Water Resources Control Board told the Bureau of Reclamation that it violated requirements to keep water flowing through the watershed, in part by allocating too much to agriculture and failing to adequately prepare for drought after a dry 2020.

The bureau had initially aimed to preserve enough cold water in the reservoir to keep nearly half of this year’s young winter-run Chinook class alive. By July, it said those initial cold storage benchmarks could no longer be met and now expects a death rate of 80%.

According to Bureau of Reclamation Regional Director Ernest Conant, providing water to settlement contractors like Glenn-Colusa impacts storage levels. But predictions changed because of unexpectedly high rates of depletion downriver — evaporation and potentially unlawful diversions directly from waterways that are difficult to track.

“We started this year with a higher storage level than in previous critical years, certainly higher than 2015,” Conant said. “So, I mean, I think we have prudently planned. This is just an unprecedented year.”

Conant said the agency plans to take a critical look at the way it approaches weather forecasting as water managers throughout the West face record snowpack evaporation. This week, federal officials declared the first-ever shortage from the Colorado River as its largest reservoir, Arizona’s Lake Mead, fell to record lows.

‘An indicator from the ocean to the rivers’

Shasta Lake is currently at 29% capacity and falling. And without enough cold water in the reservoir, state officials are warning of a near complete loss of young Chinook salmon in warm waters of the Sacramento River, which runs from the Klamath mountains out to the San Francisco Bay.

Fall-run Chinook salmon, which aren’t endangered but support California‘s commercial salmon fishing industry, stand to be adversely affected by drought conditions as well, with the potential for lasting effects on future populations that could raise retail prices in the long run.

Jordan Traverso, a spokesperson for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, said that the mortality of adult endangered salmon that hadn’t had the chance to spawn was more than 20% higher than average this year due to dry river conditions and high water temperatures.

“The greater challenge for winter-run Chinook salmon in 2021 is ensuring that suitable water temperatures can be maintained in the Sacramento River for the developing eggs and embryos that must remain in the gravel before hatching,” she said in an email.

The winter-run Chinook salmon native to the Sacramento River are born in freshwater rivers, journey to sea and live in the Pacific for two to three years before coming back as adults to spawn the next generation.

The fish historically swam high into the mountains to spawn in cold water, but since the construction of Shasta Dam, they have adapted to breed in front of it.

Cold water releases into the Sacramento River are meant to preserve water temperatures at or below 56 degrees, keeping eggs and young salmon from dying in the warm river. Dwindling cold water in the reservoir means less is available for the fish.

“Winter-run Chinook is a species that’s teetering on the verge of extinction, so losing a whole year class really does not help,” said Andrew Rypel, a fish ecologist at UC Davis.

In the 1960s, adult spawning classes were more than 100,000 large, he said. Now that number is 10,000 in a good year.

Unlike rice farmers who benefit from a water rights system that prioritizes seniority, the ancestors of Winnemem Wintu tribe leader Caleen Sisk, who fished Chinook out of the same river for thousands of years, were dispossessed by it.

Construction of Shasta Dam flooded the tribe’s lands, blocking access to ritual sites and breaking what the tribe sees as a covenant with the fish that once swam miles up their native McLoud River into the mountains.

Salmon are a critical part of the ecosystem, transferring nutrients from the sea to freshwater habitats along their journey, said Sisk, but she fears that message falls mostly on deaf ears among government agencies tasked with managing water.

“Can we do without salmon? Some people think we can. We believe we can’t,” she said. “They’re an indicator from the ocean to the rivers. It’s like miners going down into the mines without a canary. They can do it, but there’s gonna be a whole lot more problems.”

History repeating

A similar chain of events played out in California’s punishing 2014 drought, when only 5% of the year’s juvenile Chinook survived after the Bureau of Reclamation cited inaccurate computer models for underestimating the amount of cold water storage needed.

“We’re repeating that disaster and it’s very frustrating to watch,” said Doug Obegi, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council in San Francisco.

“Drought makes the challenges much harder, but we have contracts that promise so much water that you have to drain the reservoirs to be able to meet them in a year like this,” he said, pointing to the Bureau of Reclamation’s legal obligations to districts including those that serve Sacramento Valley rice farmers.

If water rights can’t be fulfilled during drought years without letting close to an entire class of endangered Chinook die, Obegi thinks those districts’ contracts need to be reconsidered.

But Glenn-Colusa Irrigation District General Manager Thad Bettner said growers shouldn’t be forced to conserve unless urban areas are doing the same. Measures such as voluntary reductions, which he said the district implemented this year, or selling more water down south by fallowing fields, could help avoid disaster in the next drought.

“This is the water rights system that we inherited from our forefathers. All people say is ‘Well, maybe it’s not working.’ But it’s like, then what do you want to change it to?” Bettner said. “Until we have that sort of conversation, I think this is a system we know we can make work.”

Asked whether flooding fields like hers could have played a role in depleting the cold water pool for salmon, Gallagher said the answer is above her pay grade. She had hoped that letting one of her rice fields fallow and selling the water down south later in the season was doing her part to maintain storage.

“I don’t know how it could be my fault, and I don’t know how it could be [the bureau’s] fault. I just think we don’t have a system that’s working well in a drought year and we’re just doing our best to try and make it through,” she said.

Settlement contractors are one part of the legal battle over the state’s authority to regulate California’s longest-standing water users that makes its water rights system “wholly unsuited to the modern state and even more wholly unsuited to a region facing climate change,” said Michael Hanemann, environmental economist and former UC Berkeley professor.

After studying water rights for 30 years, he said the big question is whether the state can legislate structural changes to the system and extend the authority of regulating agencies to the most senior rights.

The state water board is currently “muddling through” with emergency regulations similar to those that Gov. Jerry Brown empowered the state water board to enact for the first time in 2014, Hanemann said.

“Up to now, legislation that was far reaching enough to change the system could never pass because the vested interests were too powerful,” Hanemann said. “All of this is good, but it’s not doing much without passing legislation.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.