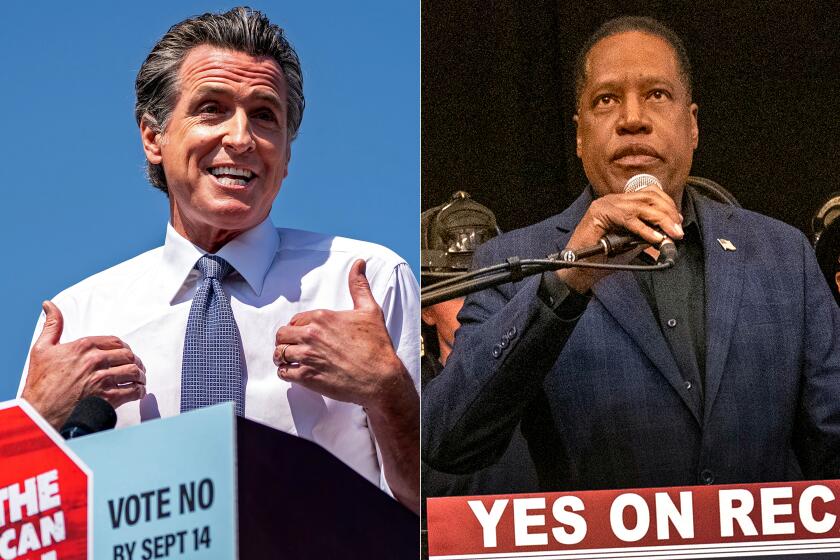

It’s now Larry Elder’s California GOP. What’s his next move?

Although the effort to recall California Gov. Gavin Newsom failed, the lightning two-month campaign appears to have had at least one clear beneficiary — Larry Elder.

The conservative talk radio host jumped to the front of the pack of 46 recall challengers soon after he entered the race on July 12, enhancing his brand as a media provocateur and potentially paving the way for a future run for office.

His showing Tuesday, when he led the challengers by a wide margin, could establish him as the putative leader of the state’s Republican Party.

Some of his most ardent followers have said they hope Elder will run next year, to challenge Newsom for a second time.

Asked about a 2022 run, Elder told KMJ radio in Fresno on Tuesday: “I have now become a political force here in California in general and particularly within the Republican party. And I’m not going to leave the stage.”

But his path to a victory would be even more difficult then, when he would have to receive a majority of the vote in a state where Democrats outnumber Republicans nearly 2 to 1.

Here’s what we know after the polls closed about the attempt to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Tuesday’s results represented a stark dichotomy for Elder: The Los Angeles native, making his first run for office at 69, rocketed past more experienced candidates to become the darling of conservatives. That put him tantalizingly close to becoming the first Black governor in the state’s 171-year history.

But his unbending conservatism — against abortion rights, opposed to the minimum wage and prepared to reverse COVID-19 vaccine and mask requirements — likely repelled enough voters in liberal-leaning California to help drive a considerable segment of the electorate toward keeping Newsom in office.

“He is now the leader of the resistance in California, or at least one of the biggest leaders,” said Carl DeMaio, a San Diego talk radio host and chair of the Reform California political action committee. “If he does want to run again, there is no doubt he is the [Republican] nominee. There is simply no doubt.”

But dominion over a small conservative “resistance” — dominated by a shrinking minority of older, white voters — is not a formula to return Republicans to power in California, said GOP consultant Mike Madrid.

“You can say you remained pure in defeat, but that’s just a martyr candidacy,” Madrid said. “It appeals to a core group that is the fastest-shrinking demographic in the state and in the country.”

Elder insisted into the final days of his campaign that he would unseat Newsom, even as polls began to show the pro-recall vote being overwhelmed by votes to keep Newsom in office. When asked last week about a possible 2022 rematch with the governor, Elder did not respond directly.

Weeks before Californians went to the polls, some right-wing activists — as well as leading GOP candidate Larry Elder — began sowing doubts about the integrity of the vote.

“A lot of people have invested their hopes and dreams in me,” Elder said. “A lot of people feel that I can make California better.”

If Elder chooses to return to his work as a talk show host, he should find his stature markedly enhanced, industry analysts said.

“He will be a huge winner in his media career because his profile has been raised exponentially since this began,” said Michael Harrison, publisher of Talkers, a trade publication for the radio and TV talk industry. “It’s been a tremendous victory for him.”

The self-proclaimed “Sage from South-Central” has been a fixture on Los Angeles radio for most of the last 30 years, first on KABC AM-790, briefly via his own streaming outlet and, since 2016, on AM-870.

The leading California recall candidate won’t waver, even when it costs him listeners, and his best friend. Now talk radio standout wants to replace Gavin Newsom as governor of California.

Elder took a hiatus to run for governor, but he will be welcomed back by the Salem Radio Network, which delivers his program to 115 stations around the country and about 260 other cable and HD platforms.

Elder’s bosses made it clear they hope to capitalize on the wave of attention he received after entering the recall race.

“For stations that have now seen this campaign and have seen how good Larry is, it’s time to go back to those stations,” said Phil Boyce, the senior vice president for Salem who oversees the network. “I expect that he will pick up stations in the future because of this.”

Elder has long told friends that he coveted a national television presence, though he has not spoken publicly about whether he still holds those ambitions. He has been a guest on Fox News programs 220 times in the past five years, but representatives at the conservative network declined to say whether they would consider Elder for a regular paid position.

Elder came late to the recall campaign, but quickly outpaced his rivals. He jumped to the head of the polls and raised more campaign funds, particularly among small donors. By late August he had raised more than $2.3 million from those giving less than $100. That was more than three times the amount his four closest competitors combined collected.

Verbally nimble and outspoken about the power of personal responsibility, Elder hammered libertarian positions he has aired for years. He called for less government intrusion, the right of parents to choose their children’s schools and for increased management of forests, to reduce the risk of wildfires.

Larry Elder leapfrogs the others vying to replace Newsom, with provocative stances from firing teachers to downplaying the dangers of secondhand smoke.

He declined to debate other challengers. Though they maligned him in his absence, the newcomer appeared only to grow in stature.

A threat to Elder’s candidacy arose in mid-August when his one-time fiancee and producer, Alexandra Datig, accused him of emotional abuse, pushing her and checking his pistol to see if it was loaded during an argument about their relationship.

Elder denied that he ever brandished a weapon at Datig, or anyone, and called the claims a distraction from the real issues in the recall campaign.

Rival candidates called on Elder to drop out of the race. So did the Sacramento Bee editorial board. But Elder ignored them and appeared to suffer no harm with his core supporters. (Los Angeles prosecutors declined to investigate, saying the statute of limitations had run out on the six-year-old accusations.)

To his most ardent backers, Elder was being targeted with slurs because of his truth telling.

“Larry won’t be bought by the unions and big tech. He will work for all people, not just the people in his party,” one supporter, Susann, said via Facebook. “I don’t want mandated vaxs, mandated masks in our children’s schools. And, most importantly, I want school choice for my grandchildren.”

Many Elder fans said they viewed him as the antidote to an overreaching government.

“We need to fight for freedom,” said Estrella Harrington, after watching Elder speak at a mall in Orange County’s Little Saigon. Harrington, an immigrant from Indonesia, said of Elder’s 15-minute presentation: “It’s perfect. It’s beautiful.”

Elder and some of his followers have signaled that they may not accept a loss as legitimate. The candidate said his campaign had created its own “voter integrity board,” composed mostly of lawyers who were prepared to file lawsuits if they detect election fraud.

Before a vote had been counted, multiple figures on the right — from Fox News personality Tucker Carlson to former President Trump — suggested Newsom would benefit from an unfair count.

But veterans of the state’s Republican politics said the GOP in California would do better to follow a more moderate course. They pointed to heavily Democratic states like Maryland and Massachusetts, where Republican moderates won the governorship.

“Any candidate that only appeals to the base, to 32% of the electorate, and at the same time energizes a lot of the other 68% of voters, that is not going to be helpful for a Republican candidate,” said Rob Stutzman, who was a spokesman for Arnold Schwarzenegger, the state’s last Republican governor.

Elder carried with him three decades of provocative right-wing rhetoric that Newsom turned into a scary wake-up alarm for snoozing Democrats, columnist George Skelton writes.

Radio host DeMaio scoffed at pundits who said Elder and other Republicans need to be more moderate. “It’s like saying Republicans should have backed a candidate more like a Democrat,” DeMaio said. “No Republican voter is going to listen to that.”

Dennis Prager, the talk radio host who has been one of Elder’s mentors, said he believed his campaign had made people realize “how much damage the Democrats and left-wing policies have done to minorities.” He said Elder had been particularly effective in exposing the “egregious double standard” that allowed privileged children, like Newsom’s, to attend in-person classes during the pandemic, while most public school students languished at home.

Prager said Elder had given no hint whether he would return to the radio or pursue another run for governor. “I would like Larry to do anything that enables him to be heard by ever larger numbers of people,” Prager said.

Days before the election, Elder responded with a smile when asked what he would do if he lost. “Don’t be so negative,” he said. “I’m going to win this one.”

Regardless of the outcome, he said he planned to continue to talk about expanding educational opportunity, improving the state’s electric power system, checking the spiraling cost of living and reducing homelessness.

“I don’t know for sure what my journey is going to be,” Elder said, “but my life has now changed forever.”

Times staff writers Stephen Battaglio in New York and Julia Wick in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.