5 takeaways from Newsom’s big win in California’s recall election

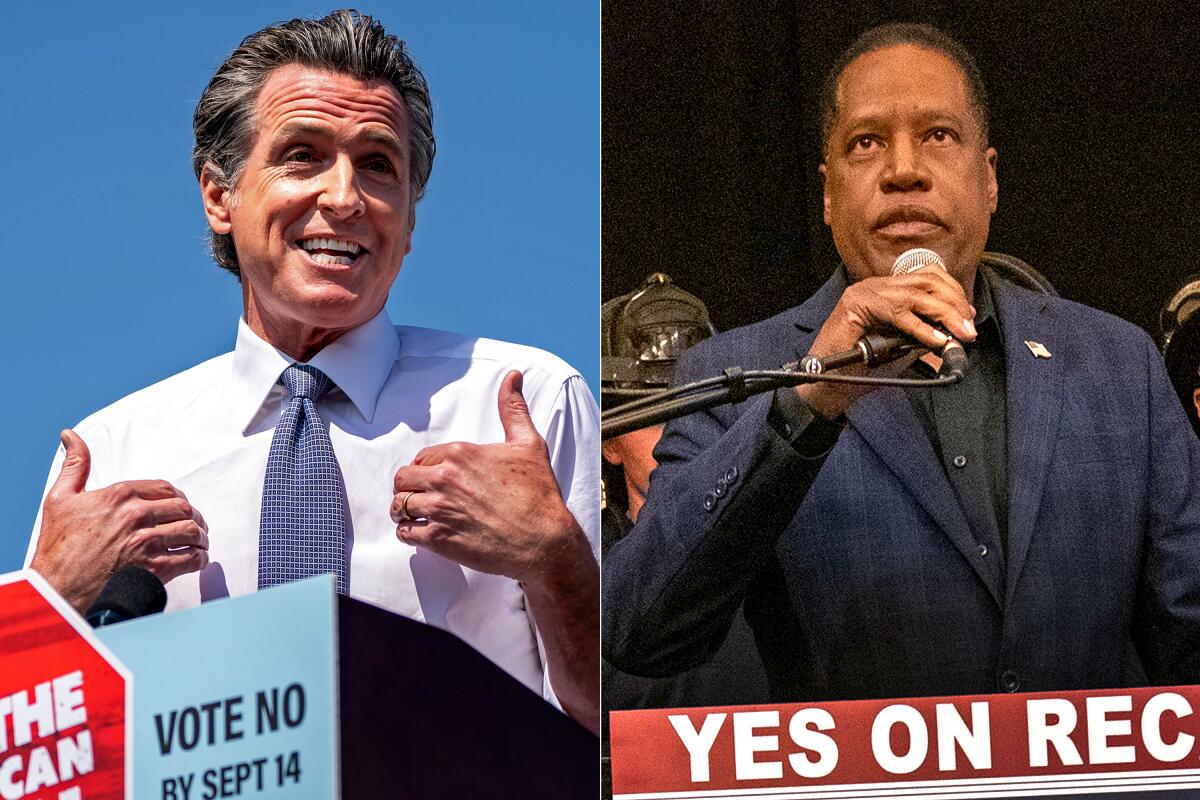

A recall campaign that at one point appeared poised to upend Democratic politics in sapphire-blue California concluded Tuesday with the status quo preserved, as Gov. Gavin Newson handily beat back an effort to oust him from office.

A strong GOP showing at the polls on election day could not match Democratic dominance in early voting. Concerns among Democrats over the summer that their party’s voters were more apathetic than highly motivated Republican ones resulted in a torrent of spending on television and outreach efforts to every part of the traditional Democratic coalition, including labor, minorities and women.

The emergence of conservative talk radio host Larry Elder in July provided the perfect foil for Newsom. The governor went from casting the recall as a naked Republican power grab to hammering on a one-on-one contrast with Elder, his decades-long record of inflammatory remarks and his plans if elected to office.

The result was that the California electorate reverted to form and voted as it has in recent gubernatorial elections, giving the Democrat a double-digit victory, with nearly three-quarters of the vote counted.

The recall campaign against Gov. Gavin Newsom was supposed to unify California Republicans. Instead, it deepened divisions between the party’s grass-roots conservatives and moderate establishment.

Newsom’s mandate

A key question is how Newsom will act in the aftermath of the recall. Will he be emboldened by his victory, or will he be humbled by the fact that Democrats had to spend tens of millions of dollars to ensure he retained his seat, in a state where his party enjoys an advantage of 5 million people in voter registration?

The large margin of Newsom’s victory provides the governor with a mandate to continue pursuing liberal policies on issues such as healthcare, climate change and immigration.

Roger Salazar, a Democratic consultant who served as press secretary for former Gov. Gray Davis, said he expects Newsom to emphasize homelessness, crime, wildfire preparation and the pandemic between now and next year’s election.

“All of those things are all tied into an economic recovery that he’s going to want to have major progress on as he faces reelection. He’s moving from one election to another almost instantaneously,” Salazar said.

The governor could be a front-runner for president — if fellow Californian Kamala Harris wasn’t already Biden’s No. 2.

The Big Lie — California version

Republicans — notably former President Trump and Elder — sought to undermine the integrity of the recall before voters headed to the polls Tuesday by saying the election was rigged.

“Does anybody really believe the California Recall Election isn’t rigged?” Trump said in a statement.

There are multiple verification processes to prevent fraudulent voting, and there is no evidence of cheating, but some Republicans are laying the groundwork for baselessly challenging the results of the election.

“They’re trying to throw battery acid on our Constitution, on our electoral norms,” Newsom advisor Sean Clegg told reporters Monday, before a rally in support of the governor that featured President Biden. “And it’s a preview of coming attractions. We’re going to see the same thing in 2022 and the same thing in 2024.”

Some Republicans speculated that such baseless claims suppressed voter turnout Tuesday. Others, including former state GOP chairman Ron Nehring, said the messaging played into Russian President Vladimir Putin’s efforts to undermine American democracy.

“False claims of election rigging are also bad politics, because it provides an excuse for not building a bigger campaign or a bigger party,” tweeted Nehring, who supported former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer in the recall election.

The COVID-19 paradox

The pandemic put Newsom in jeopardy, but it also saved him. And COVID-19 may provide a road map for Democrats as they head into the midterm elections. On Monday, Biden leaned heavily into Newsom’s handling of the pandemic to argue that the governor should not be recalled.

“We need courage. We need leadership,” he said, urging California Democrats not to be complacent. “We need Gavin Newsom, a governor who follows science and had the courage to do what’s right.”

The initial recall petition had nothing to do with the pandemic, but the restrictions put in place to stop the coronavirus’ spread — coupled with the four extra months recall backers were granted to gather signatures — made the difference in qualifying the effort for the ballot.

Then, after most Californians had been vaccinated, the Delta variant emerged. California’s infection, hospitalization and death rates are lower than in states where leaders pushed back against mask and vaccination mandates. Newsom used this disparity to argue that if the recall were successful and he was to be replaced by a Republican — particularly Elder, who pledged to roll back such restrictions — Californians would die.

The limitations of Larry Elder

There’s a certain logic to it: If the 2003 recall could lead to an action movie star being elected governor, why not a talk radio host in 2021?

But while Elder’s celebrity propelled him to the top of the contenders hoping to replace Newsom, his candidacy underscored his shortcomings. A first-time candidate, he had years of provocative on-air commentary he had to explain, and he showed little ability to garner support beyond the state’s conservative flank.

Newsom was all too happy to run against Elder, but lurking in the subtext of those attacks was Trump. In a state that rejected Trump by nearly 30 percentage points in 2020, associating Elder with the ex-president was an easy way to rally Democrats against the recall. If Elder wants to stay politically relevant, he’ll need to find a way to reach voters who aren’t Trump fans.

The California Republican Party did not endorse Elder (or any other candidate) in the recall, but its future will be scrutinized closely. This race was the party’s best chance in a statewide election in more than a decade because of the lower threshold to win office: If more than half of voters had supported the recall, the top vote-getter among the 46 replacement candidates would have becomegovernor, regardless of how few votes that person received.

Going forward, the state party will focus on an area where it has had success in recent elections: congressional races. Indeed, much of the party’s efforts in the recall were focused on districts it hopes to hold or flip next year.

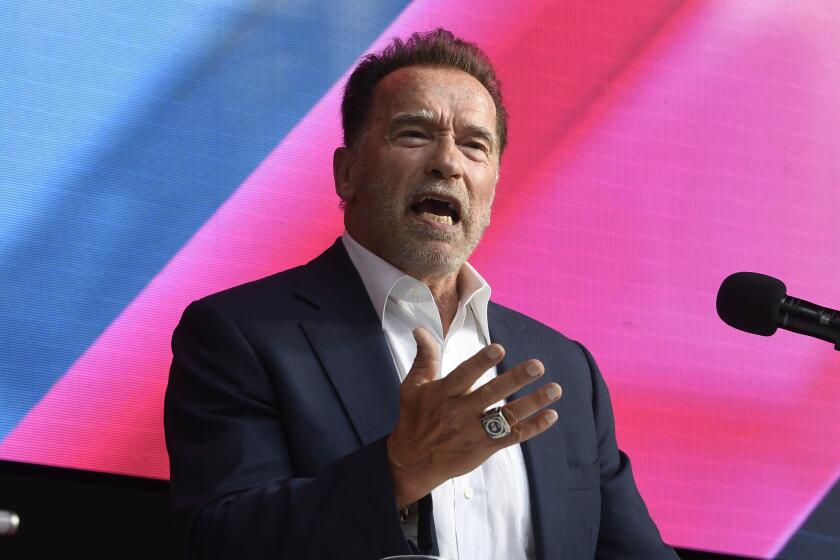

Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger, who won office through a recall, says he’s glad Newsom wasn’t ousted

Recall reform

Even before votes were cast, this recall election has prompted calls for reform of California’s electoral rules. Critics argue that it’s too easy to qualify a recall for the ballot and that the two-question format — which places both the recall question and a list of replacement candidates in front of voters simultaneously — is confusing. It’s also expensive, with the special election projected to cost $276 million in taxpayer dollars.

Among the proposals being floated is an increase in the number of signatures necessary to place a recall on the ballot; under the current rule, 12% of the voter turnout from the prior gubernatorial election is required, a rate that’s among the lowest in the nation.

Also being considered is allowing recalls only in cases of criminal conduct or malfeasance, adding the candidate who is the target of the recall to the list of replacement candidates and having the lieutenant governor assume the post if a gubernatorial recall is successful. Another proposal is to divide a recall into two special elections — one asking whether an elected official should be ousted and, if that is successful, a separate election on the replacement candidate.

Darry Sragow, a Democratic strategist and publisher of the nonpartisan California Target Book, said he thinks the recall process needs to be fixed but is skeptical reforms will ultimately be made.

“Voters like having this direct democratic check on what is otherwise a representative democracy,” he said — particularly in Western states, where there is a long-standing culture of distrust in government.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.