‘The mood is grim’: Death threats, violence, intimidation mark another pandemic school year

JACKSON, Calif. — On Day One of class, the father of a little girl got so angry because she had to wear a face mask that he cussed out a principal and punched a teacher in the face.

By the second week, students in this small county in the Sierra Nevada foothills started testing positive for the coronavirus as the highly contagious Delta variant pummeled rural California.

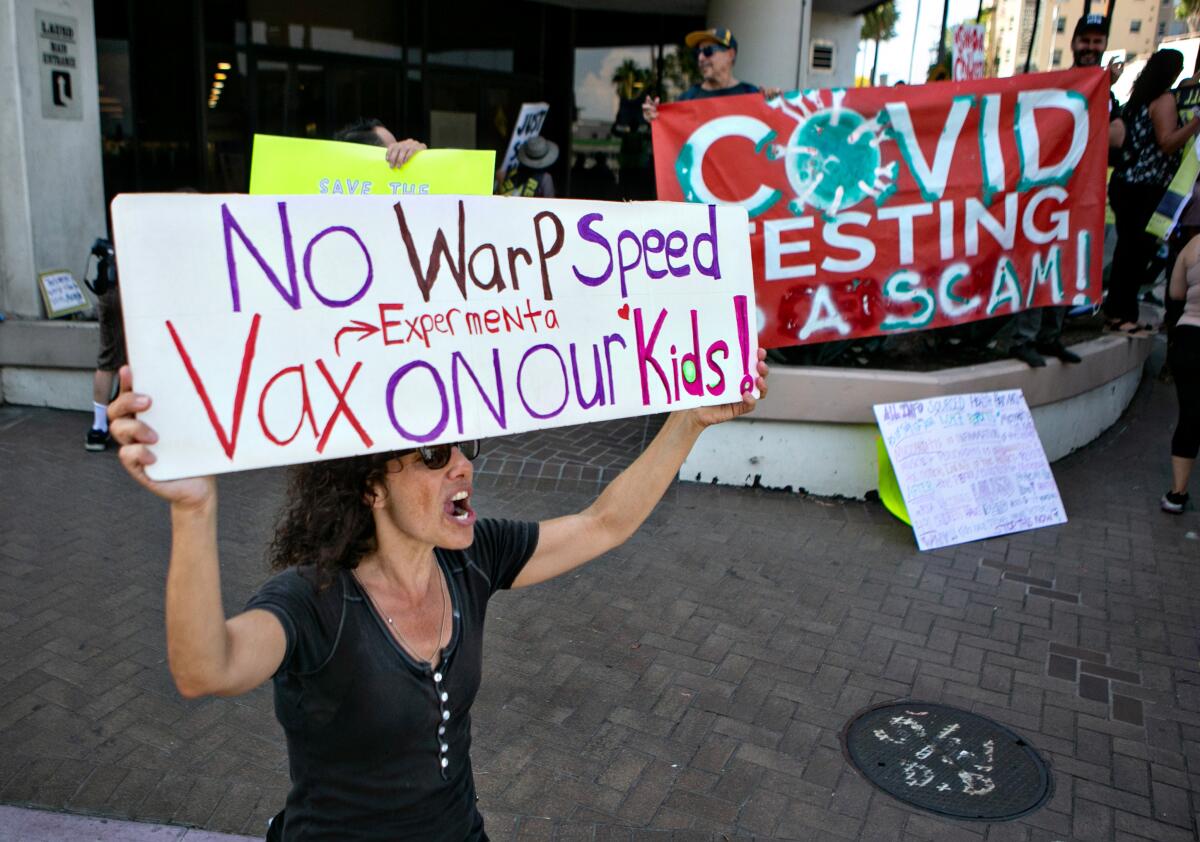

Some teachers vowed to quit if vaccines become mandated. Families had pulled children out of sports to avoid weekly coronavirus testing. Outraged and crying parents had flooded school board meetings, disparaging masks as a “dirty piece of cloth” and a face-covering requirement as “a fear-based decision.”

Welcome to your new job, Torie Gibson.

This summer, Gibson started as superintendent for the Amador County Unified School District. Just before school started, things looked bright: Coronavirus case numbers were down, California was reopening and masks were coming off. But she soon realized that as the Delta variant emerged, masks, testing and quarantines would once again be required. That meant trouble.

“I was feeling PTSD,” said Gibson, 45, said from her office in Jackson. “Not much rattles me. I can go with the punches, I can be screamed at, I can have complete chaos erupt and am like, ‘We’ve got this.’ ... But I said, ‘This is going to be a really rough year.’”

Anti-maskers have emailed her death threats. In late September, police came to one of her schools after a family directed their child to attend class unmasked and refused to leave until authorities were called.

In the second full academic year of the pandemic, such behavior has reared its head on school campuses across the U.S.

Last week, the National School Boards Assn. sent a letter to President Biden asking for federal assistance to prevent violence and investigate threats against public school officials and children.

“America’s public schools and its education leaders are under an immediate threat,” the letter said.

The organization asked the U.S. Department of Justice, the FBI, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Secret Service and its National Threat Assessment Center for help.

After withstanding heated debates over reopening classrooms, schools are now bearing the brunt of public anger as the pandemic continues to drag on with new variants, said Chip Slaven, interim executive director of the National School Boards Assn.

California education leaders say the challenge follows a trend that encouraged school vandalism last month.

“America, everyone needs to take a step back here and take a deep breath. We all care about our students and our public schools,” Slaven said. He added that threatening outbursts — many of them fueled by conspiracy theories and misinformation — have “become very common, and that’s troubling.”

The school boards group called threats and violence against schools “the equivalent to a form of domestic terrorism and hate crimes.”

In Michigan, a father was ejected from a school board meeting because he gave the Nazi salute and yelled, “Heil Hitler!” after another parent spoke in favor of masks. The father of a boy who was ordered to quarantine came to the child’s Arizona elementary school with two other men carrying zip ties and threatened a principal with citizen’s arrest. At a school board meeting in Florida, where Gov. Ron DeSantis has banned mask mandates in public schools, a protester doused a tray of masks with lighter fluid and set it on fire.

Here in California, members of the extremist Proud Boys have joined anti-mask and anti-vaccine protesters at school board meetings in Placer County.

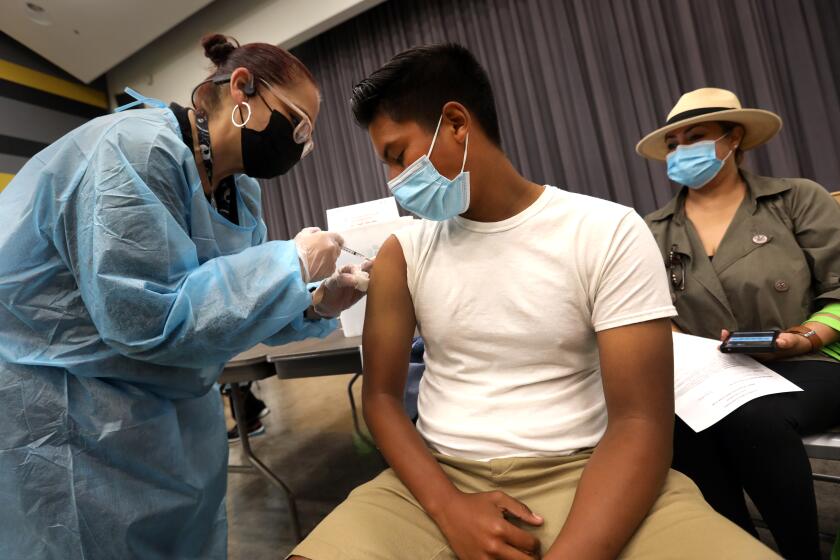

The COVID vaccine mandate would apply to students 12 and older after they become eligible for a fully approved vaccine.

“The mood is grim,” said Troy Flint, a spokesman for the California School Boards Assn. “School board members in many cases feel unsafe, they feel threatened, or they feel that they have been made the villain in a play where they weren’t able to write the script.”

On Friday, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced the country’s first statewide mandate requiring all eligible public and private schoolchildren to get vaccinated against COVID-19 after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorizes full approval of the shots for their age groups. He also announced that school employees — who have had the option to test weekly if they are unvaccinated — would be required to get inoculated once children are required to.

“On one hand, a statewide mandate removes some of the pressure from school boards,” Flint said. “But in areas where there is strong resistance, it could intensify the backlash.”

Last month, the California school boards organization sent a letter to Newsom asking for state intervention. Often, the letter says, school districts contact authorities to restore order to raucous meetings or to enforce mask mandates, but law enforcement declines to do so.

“In numerous cases, law enforcement officers — in brazen defiance of the law and their professional oath — have explicitly stated they will not enforce safety mandates or restrain those whose actions willfully disrupt a meeting and prevent it from proceeding,” says the letter from Vernon M. Billy, the group’s chief executive.

In San Diego County last month, anti-mask protesters forced their way into a Poway Unified School District board meeting — which had limited in-person attendance and was being livestreamed for the public — and refused to leave. According to the school district, officers with the San Diego Police Department advised board members to adjourn to deescalate the situation. The police department did not respond to requests for comment.

Social media video showed officers standing by as protesters who declared the board members had vacated their seats tried to swear themselves in as the new school board.

At a later meeting, Superintendent Marian Kim Phelps said that most of the unruly demonstrators did not have children attending Poway schools.

Even without the threats, this academic year has been overwhelming for administrators now tasked with coronavirus contact tracing, testing and the complicated logistics of quarantine, said Stuart Packard, president of the Small School Districts’ Assn.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Across the state, he said, many superintendents retired last year, and “it is on the mind of every school administrator near the end of their career right now — ‘How much more can I take?’”

Packard, superintendent of the Buttonwillow Union School District in Kern County, said his school erected a tent to let half the student body sit outside to maintain social distance. Cafeteria workers take pictures during lunch to see who is sitting with whom so they can do contact tracing. And Packard himself gives students rapid coronavirus tests.

When asked how his staff was faring this year, Jon Ray, the superintendent-principal at Weed Union Elementary School in Siskiyou County laughed ruefully.

“I’ve gotta be honest, we’re running full-tilt and it’s stressful,” he said. “I feel like we’re a medical clinic.”

At his rural school — where enrollment shot up nearly 40% because it stayed open for on-campus instruction last year — any adult who enters the campus must provide proof of vaccination or be tested on site, he said. That includes parent volunteers and construction workers repairing buildings that were evacuated this year because of black mold.

The second week of class had to be all-virtual as coronavirus cases peaked in Siskiyou County in August. Last week, a staff member’s mother died from COVID-19. And Ray has had to hire therapists to help children dealing with depression and suicidal thoughts exacerbated by the pandemic.

In Amador County — a conservative county where coronavirus hospitalizations hit a high this summer — Torie Gibson’s husband, Mark, worries for her safety during school board meetings and finds himself monitoring social media for threats. He looks over his shoulder when they’re in public in their new town.

“We live in the community, which we love, but at the same time, it’s, what do we come up against?” said Mark Gibson, a therapist. “I find myself, when we’re out and about, I’m always kind of observing. I’m not really anxious, but I wonder, ‘Is this person going to know who she is?’”

It was on Aug. 11, the first day of class, that a father showed up late to pick up his fourth-grader from Sutter Creek Elementary School, Torie Gibson said. He became irate as his daughter and the principal walked outside wearing masks because he could see inside a teachers’ lounge where teachers were unmasked.

If teachers are vaccinated and there are no students present, they can remove their masks indoors, Gibson said.

“Dad saw that and just flipped his lid,” she said. “The little girl tried to explain to her dad, ‘Dad, it’s fine. I don’t wear it outside; I only wear it indoors. It’s OK.’”

The COVID-19 pandemic, then the Caldor fire and smoke, closed the theater in rural Volcano, Calif., for more than 18 months. But the show must go on.

The father left with the girl, then returned to confront the principal. A teacher who figured “it would get volatile” went into the principal’s office, Gibson said, and was punched by the father several times in the head and face. The teacher is still having vision issues in one eye, Gibson said.

The father, Jason Wages, 49, of Sutter Creek, has been charged with multiple misdemeanor counts, including battery on a school employee, according to the Amador County district attorney’s office.

Wages could not be reached for comment.

The story went viral, and the new superintendent spent the rest of that first week juggling media interviews, student coronavirus testing — and moving into her new home.

Then there was the Caldor fire, which started that first weekend of class, forcing evacuations in Amador County and early school closures because of smoke.

Gibson said she’s now worried that teachers and other school staff will quit over the new vaccine mandate. Her district is already short-staffed. Bus routes are canceled when there are not enough drivers, and it can be tough to cover for teachers quarantining after exposure to the virus.

Meanwhile, it’s the children in her countywide district of 4,200 pupils who seem to be behaving best.

“The kids are like, ‘Please just let me go to school. Don’t make me stay home with my parents all day,’” she said. “The adults haven’t always behaved real well.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.