Major California earthquake would knock out cell service, communications, study finds

SAN FRANCISCO — A major earthquake in California is likely to knock out many communications services for days or weeks, including the vast majority of cellphones in the areas closest to the epicenter, according to a landmark new analysis by the U.S. Geological Survey.

The widespread disruption would imperil the public’s access to 911 operators and lead to delays in reporting fires and calls for medical help.

Cell towers are vulnerable to sustained power outages. The same goes for cellular equipment on power poles and buildings at risk of extreme shaking, liquefaction and fire, the USGS said. California’s cellphone networks have been notoriously unreliable during blackouts that occur during life-threatening emergencies, such as during wildfires in 2019, where wide swaths of the San Francisco Bay Area were cut off from cell service for significant periods.

In a grim estimate of the challenges, a magnitude 7 earthquake that struck on the Bay Area’s Hayward fault could leave Alameda County — its hardest hit area — able to provide only 7% of the demand for voice and data service after the quake. That is identical to the communications service failure in New York City after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, when 93% of cellphone calls failed.

The findings in the USGS study are one of many vulnerabilities uncovered by the government agency, which formally presented its findings at a news conference Thursday.

The report comprises about 780 pages, adding to nearly 600 pages of findings released since 2018 on the so-called HayWired scenario. The report is the third volume in a series of reports researched over six years focused on a future earthquake on the Hayward fault; the final volume was written by 20 main authors and 80 contributors.

People are much more important than kits. People will help each other when the power is out or they are thirsty. And people will help a community rebuild and keep Southern California a place we all want to live after a major quake.

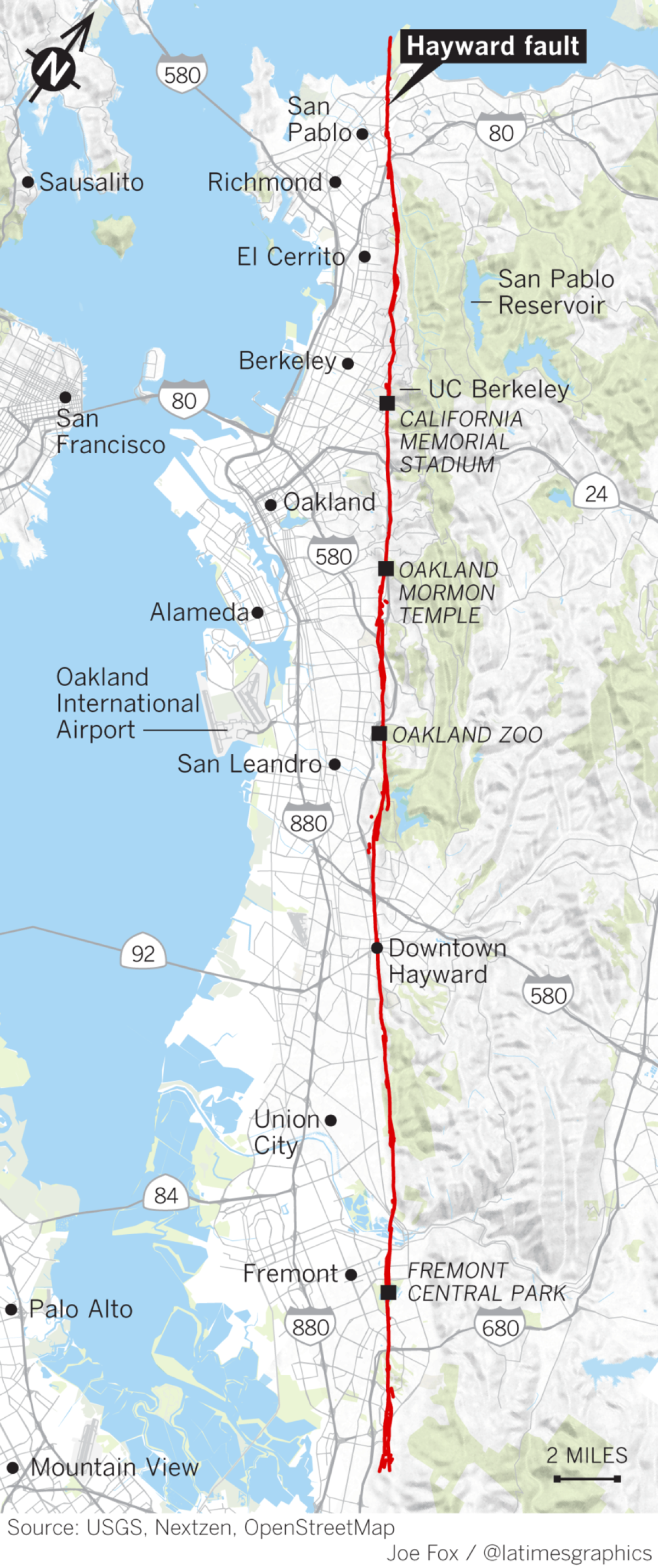

The Hayward fault has been called a “tectonic time bomb,” and a major quake on it represents a nightmare scenario because it runs through densely populated areas with old buildings, including directly beneath the East Bay cities of Oakland, Berkeley, Hayward and Fremont.

The Hayward fault is one of California’s fastest moving, and on average, it produces a major earthquake about once every 150 to 160 years, give or take seven or eight decades.

It has been 153 years since the last major quake — a magnitude 6.8 — on the Hayward fault. The USGS estimates a magnitude 7 quake today on that fault could result in at least 800 deaths; hundreds more could die from fire following the quake, which would make this scenario California’s deadliest since the great 1906 earthquake destroyed much of San Francisco.

In this hypothetical seismic scenario, electricity services could be out for weeks, while gas and water service could be interrupted for months. The USGS estimates an East Bay resident could be without water from six weeks to six months, and water supply outages could hobble firefighting efforts.

Transportation systems could be disrupted for years.

The USGS report said the region’s backbone commuter rail system, BART, could see its Hayward train yard heavily damaged or collapse, while train stations in Oakland, Hayward and San Leandro could be so damaged that it could take one to three years to repair them. The USGS simulations for the kind of ground shaking that could occur are far worse than for what BART was designed, meaning even some seismically retrofitted facilities at the Hayward train yard could be destroyed, the report said.

While BART’s earthquake safety program was designed to keep commuters alive during an earthquake, some sections of the system — including parts of the East Bay — are not equipped to keep the transit service operational after a severe quake, the report said.

The USGS also identified more than 50 bridges at high risk for damage and collapse, and noted it could take three to 10 months to repair them. Many are along Interstate 880, a key artery connecting Oakland to San Jose; other freeways at risk include Interstate 680 between Fremont and Pleasanton and Interstate 580 between Oakland and Pleasanton.

With so many freeways that could potentially be damaged, “emergency response, evacuation and debris removal would be hampered and recovery ... could take longer than anticipated,” the report said. Destruction to East Bay freeways could be so bad it may be easier to flee by heading over the bay to the west, toward San Francisco and San Mateo County.

Damage could turn some areas into ghost towns, a phenomenon that happened in parts of Los Angeles after the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake of 1994.

Seismologist Lucy Jones, journalists Rong-Gong Lin and Patt Morrison of the L.A. Times, and journalists Jacob Margolis and Austin Cross of KPCC/LAist discuss earthquake safety and resilience in California. Here are five things to remember when preparing for the Big One.

Neighborhoods across the East Bay, such as those in Oakland, Berkeley, Richmond, Alameda, San Leandro, Hayward, Castro Valley, Union City and Pleasanton, are at risk for having more than 20% of their buildings suffer extensive damage or be destroyed. That’s a potential tipping point in which people may decide en masse to leave their homes or workplaces — even if they’re still structurally intact — because their neighborhoods have ceased to function normally.

A similar effect occurred following the magnitude 6 earthquake that hit Napa in 2014. Some retrofitted businesses remained standing but could not immediately reopen because neighboring structures that had not been updated were so badly damaged that potential aftershocks could send them crashing into the seismically safe structures.

In a hypothetical quake on the Hayward fault, between 720,000 and 1.45 million residents are at risk of being displaced from their homes, the USGS said.

Old buildings are a major risk. In places like Oakland, Berkeley, Hayward and Alameda, there are many so-called soft-story apartment buildings, with flimsy first floors housing carports that can collapse in an earthquake, as well as old, vulnerable brick and brittle concrete residential buildings.

While Oakland, Berkeley and San Francisco have passed mandatory retrofit laws for soft-story apartment buildings — as have cities such as Los Angeles, Santa Monica, West Hollywood, Beverly Hills, Pasadena and Culver City in Southern California — many other cities have not.

Unless more is done to retrofit these apartment buildings, whose rent is generally lower than for newer structures, there could be a dramatic worsening of the supply of affordable housing if these structures are heavily damaged or destroyed in a quake.

Whether you’re on a fixed income or just trying to save a few dollars, there are ways everyone can prepare for disaster on a budget. Here’s a checklist and tips on insurance, supplies and more.

California stands to suffer $74 billion in cumulative property damage, with 1 million residential buildings and 39,000 nonresidential buildings damaged, in a major Hayward fault quake. Losses from the interruption of business would be caused mostly by property damage, but worsened because of disruptions to the supplies of water, electricity and communications.

There could be a wave of mortgage defaults, a deterioration of mental health and persistent blighted property, which could be exacerbated by years of significant aftershocks that could strike farther away from the fault, including underneath the Silicon Valley cities of Palo Alto, Cupertino and Sunnyvale.

The economic losses could send the Bay Area into a recession for five to 10 years. Nearly half a million jobs could be lost, and there would be an 8% drop in its gross regional product compared to the region’s expected growth. It could take even longer to recover if there are shortages of workers, higher costs of construction and decisions by big employers to grow jobs outside the region.

In the most heavily damaged areas of the East Bay, as many as 40% of businesses could see their operations disrupted “by extensive or complete building damage in central Alameda County and western Contra Costa County,” USGS officials warned.

There are plenty of things that can be done to improve California’s resiliency to a significant earthquake.

Old single-family houses and apartment buildings need to be seismically strengthened; so does infrastructure, such as systems that send water, electricity, fuel and communications to homes and businesses, the report suggested. More new housing, built to modern-day standards, needs to be made available before the shaking begins, and governments need to plan for a long-term recovery with a plan to finance it.

Even simple strategies could help dramatically. Telling the public to minimize voice calls and rely on text messaging would help preserve capacity for the 911 system. Telephone companies could restrict the number of phone calls a person could initiate every hour.

Telecommunications systems could be made more reliable if permanent backup power is available, either through batteries that last less than a day, along with generators that can run for three days before needing to be refueled.

A majority of U.S. residents live in wireless-only households, said David Witkowski, a co-author of the USGS report. Nationwide, 57% of people no longer have wired phones in their homes; that figure exceeds 76% among people in their late 20s and early 30s.

Newer digital landline services, such as those that receive their connection through internet service like Spectrum, Cox and Comcast, as well as through AT&T’s U-Verse, are relatively less resilient because they require backup power to keep phone services operating during a power outage.

Traditional copper-based analog landline phone service that needs no electricity — still offered by companies such as AT&T and Frontier — may end up being relatively more resilient because it receives power from batteries in the phone network, Witkowski said.

During the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, some people in the Bay Area reported still being able to make calls to their closest neighbors, but not people farther across the region or the rest of the country, he said.

It’s still possible that wired phone networks can get overloaded, “but this is less likely now that the links between wired phone switches are high-bandwidth data links,” Witkowski said. “Of course, even a high-bandwidth link can be overloaded by enough traffic.”

Long-lasting power outages can also thwart copper-based landline phone service. During the 2019 wildfires, some residents reported losing their AT&T landline service following the first 24 hours after the lights went out.

If all commonly used phone systems are knocked out, the only alternatives might be satellite phone service or amateur radio operators, as was needed in Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria.

California has made significant strides in improving earthquake safety; $80 billion has been spent since 1989 in the Bay Area alone on earthquake improvements, including $20 million each on upgrades to bridges and freeways; $19 billion on hospital retrofits; and $6 billion on water supply systems.

But that money hasn’t been spent evenly. There has been four times as much investment on earthquake safety in San Francisco on a per-capita basis compared with the East Bay, according to Anne Wein, a leading coordinator of the USGS report.

Earthquake preparedness is about communication, resilience and understanding and mitigating your risks. Our newsletter course will teach you how.

Los Angeles has made some improvements in recent years. In 2015, L.A. passed an ambitious seismic safety effort requiring soft-story apartments and brittle concrete buildings to be retrofitted. Of more than 12,500 potentially vulnerable soft-story buildings in the city, nearly 7,000 have been retrofitted.

The L.A. Department of Water and Power has also installed more earthquake-resistant mainline and trunk line pipes in recent years, intended to keep hospitals and other critical sites operating after a quake.

But there are still vulnerabilities. Most cities in California, including Los Angeles, have not required retrofits of potentially vulnerable steel buildings, which Santa Monica and West Hollywood have done. A USGS study in 2008 has said it is plausible that five unretrofitted steel buildings around Southern California could collapse in a hypothetical magnitude 7.8 earthquake on the San Andreas fault.

Wein said it’ll be important for people to think of preparedness not only as making one’s own home or business seismically ready, but also the surrounding community.

After all, what use will it be for a home or business to remain standing, but everyone else in the neighborhood is in disrepair?

“If I’m the only person in my whole neighborhood who retrofits, it won’t really help the neighborhood,” Wein said. “It won’t even really help me.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.