Black job applicant sues company for discrimination over hairstyle

A Black job applicant who had recently moved to San Diego in hopes of furthering his career in the audiovisual field filed a discrimination suit this week against an event production company, saying he was denied employment only after refusing to trim his locks.

The legal claim, which alleges violations of the state Fair Employment and Housing Act, specifically invokes a relatively new California law known as the CROWN Act (Create a Respectful and Open Workplace for Natural Hair) that bars the use of grooming policies directly targeting Black people. The lawsuit is believed to be the first such legal action filed under the CROWN Act, which went into effect in January 2020.

It amends the Fair Employment Act and the California Education Code to effectively expand the definition of race discrimination by including discrimination based on “traits historically associated with race,” such as hair texture and protective African American hairstyles, including afros, braids, twists and locks.

Today, at least 12 states have their own CROWN Acts, including New York, Virginia, Maryland, Colorado and Washington.

The target of the San Diego lawsuit is Encore Global, an Illinois event management company that has an office in San Diego. Jeffrey Thornton, a transplant from Florida who moved to San Diego this year, had been working for Encore in Orlando since 2016 until he was furloughed in March 2020 because of the pandemic.

Kari Williams has worked to make her natural hair salon a refuge for black Angelenos, including those who’ve felt pressured to alter their hairstyles to hold on to a job.

After receiving an email in October from Encore announcing a return to work, Thornton felt confident he might be able to get his old job back as a technical supervisor — working instead in San Diego — especially after getting a strong recommendation from his former boss in Florida.

“I was told that I was recommended by my East Coast references and I should find the transition to be no problem,” Thornton said of his Nov. 1 interview with Encore, held at the Hilton San Diego Bayfront. “All that was left was to discuss was the dress code, which was not surprising considering I’d be working in the hospitality environment and I would have client-facing responsibilities.

“I expected that I was to remove my ear gauges, I’d be willing to trim my facial hair but I wasn’t prepared to be told that I would need to cut my hair to comply with Encore standards.”

In an email sent Wednesday to the San Diego Union-Tribune, Encore expressed regret for any “miscommunication” that may have occurred between Thornton and the company.

“Maintaining a diverse and inclusive workplace where every individual has a full sense of belonging and feels empowered to reach their potential are core values of our business,” a company spokesperson said. “These values are key to fueling innovation, collaboration and driving better outcomes for our team members, customers and the communities we serve.

“We regret any miscommunication with Mr. Thornton regarding our standard grooming policies — which he appears to fully meet and we have made him an offer of employment. We are continuously looking to learn and improve, and we are reviewing our grooming policies to avoid potential miscommunications in the future.”

Encore, based near Chicago, is a global provider of technology and production services for events at major hotel brands across 20 countries.

Thornton’s lawsuit states that Encore required him to cut his hair so that it was off the ears, eyes and shoulders, and that it would not allow him to comply by tying back his hair.

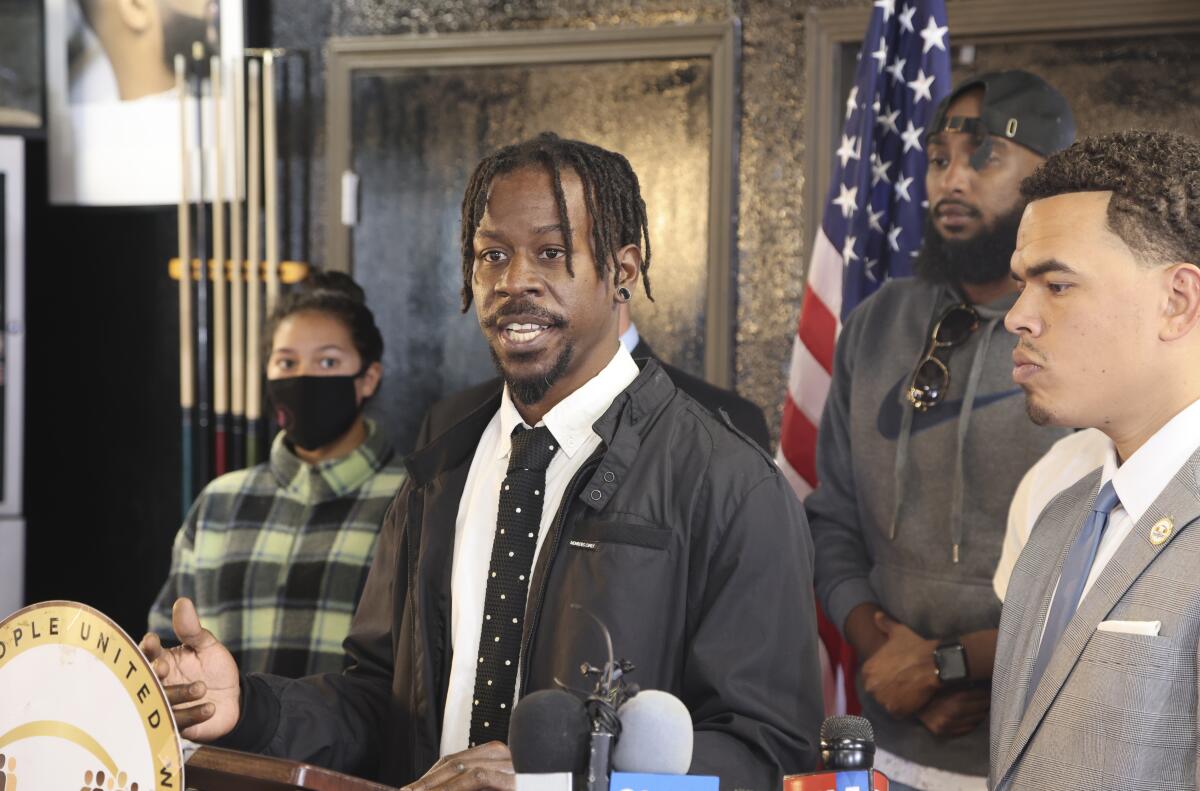

Speaking at a news conference Tuesday at the Studio Cutz Barber Shop in La Mesa, Calif., to announce the filing of the lawsuit, Thornton said he was stunned by the request.

“I told them it was a deal-breaker, I wouldn’t be able to come to terms with sacrificing my disciplinary journey and what it symbolized. I was told that if I was willing to make that sacrifice, a position would be waiting for me, which it still is, I assume.”

Five current and former employees say the city of Long Beach failed to equally pay and promote Black workers and contributed to “anti-Black culture.”

The lawsuit, filed on Thornton’s behalf by employment law attorney Adam Kent, seeks unspecified general and punitive damages and also asks for an injunction barring Encore from imposing any dress code or personal appearance policy that “violates, or tends to violate the CROWN Act, in particular, or the Fair Employment and Housing Act, in general.”

“We all expect to be judged based on our abilities and our character, but Mr. Thornton is being told it’s different for him,” Kent said. “He wasn’t being told he wasn’t competent for the position. He wasn’t told that he didn’t have the skill or training necessary. Instead, he was told what he looks like is the reason why he can’t pursue his profession, his chosen career. ... So with this lawsuit, we argue that proximity to whiteness is not to be used as a measuring stick for success.”

San Diego employment attorney Dan Eaton noted that although employers have some latitude in what they can require of their workers, there is a limit to what they can do when it crosses the line into potentially discriminatory behavior.

Employers “can certainly require employees to have neat and clean hair,” Eaton said. “What they can’t do is restrict hairstyles that have a racial origin. That is what the CROWN Act is about.”

Assisting in the effort to hold Encore accountable is San Diego civil rights activist Shane Harris, president of the People’s Assn. of Justice Advocates. Encore’s grooming requirements are nothing short of racism, Harris alleged during the news conference, which included remarks by a number of local hairstylists. In addition to supporting the legal effort, Harris said his organization plans to lobby the state Legislature and Gov. Gavin Newsom to implement a set of provisions or a task force to ensure enforcement of the CROWN Act.

“We cannot claim to be the leader on innovation, the leader against hair discrimination, and then we fail to enforce the policies we’re enacting,” Harris said.

He pointed out that Encore‘s website emphasizes stresses its commitment to “diversity, equity and inclusion” and states that its mission is to “promote development and advancement of under-represented groups within Encore by providing continuing development opportunities, coaching and mentorship.”

In a letter sent late Tuesday to Encore Chief Executive Ben Erwin, Harris requested a meeting to discuss the company’s diversity commitments as they relate “to one’s hairstyle.”

He added, “We ask that you as CEO take responsibility for this notion of discrimination, as it is your company and business that (affected) Mr. Thornton and his opportunity to get a job. Furthermore, it’s important to understand that just because this has happened to Mr. Thornton and we are bringing attention to it, does not guarantee that it won’t happen to another individual.”

Although Thornton’s legal complaint may be one of the first lawsuits in California under the CROWN Act, there have been several other employment discrimination legal actions regarding African American hairstyles in the past.

In 2007, Abdul-Jabbar Gbajabiamila, an African American of Nigerian descent, lost his job as a manager in training at Abercrombie & Fitch’s Hollister store in El Cajon for refusing to remove his cornrows, which didn’t conform with the company’s “Looks” policy,” Eaton said.

The state Department of Fair Employment and Housing challenged the firing, alleging race discrimination. But an administrative law judge dismissed the challenge in part because the store had required white employees to remove cornrows in the past. The judge also cited federal court rulings that found cornrows, unlike afros, weren’t necessarily an immutable characteristic of race.

San Diego Union-Tribune research director Merrie Monteagudo contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.