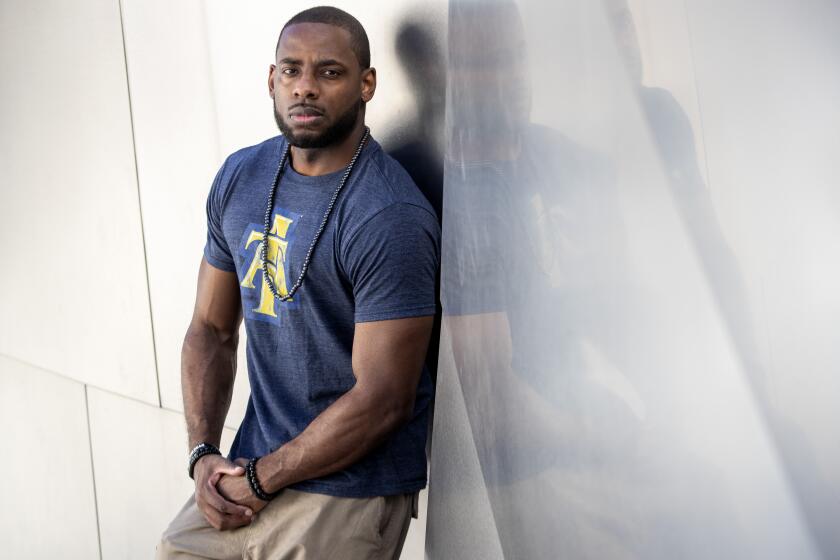

Every morning, Sergio Ayala combed his daughters’ hair into twin braids, dropped them off at school and headed to work.

He loved his job as a field supervisor at his brother-in-law’s pest control company. But he wanted to own a business and was studying to become a barber. He hoped to start a college savings fund for his three girls and toddler son.

In January, that dream was cut short. His family believes he contracted the coronavirus while practicing his barbering skills in people’s homes.

Ayala died from COVID-19 at age 37.

His partner, Lizeth Sanchez, worries she won’t be able to fill his shoes.

“I think, oh, God, what if I can’t afford to give them the education their dad wanted for them?” Sanchez said. “What if I can only afford education for one of them? It scares me.”

In California, younger Latinos are dying of COVID-19 at much higher rates than their white and Asian counterparts. Younger Black people also are dying at high rates, but the disparity is starkest for Latinos.

As more people get vaccinated, pandemic restrictions lift and the economy rebounds, the families of the young Latinos who died will feel the loss for decades to come — not just the grief but the long-term financial hardships.

It will be harder for their children to get an education and achieve upward mobility, potentially widening the class divide in the coming decades.

In California, Latinos ages 20 to 54 have died from COVID-19 at a rate more than eight times higher than that of white people in the same age group, according to a study by USC’s Department of Preventive Medicine.

Many, like Ayala, died before vaccines were widely available.

“Latinos are getting hit from all angles,” said Christina Ramirez, professor of biostatistics at UCLA. “This is going to be felt for generations to come.”

Ayala was raised by a single mother, a Salvadoran immigrant, in a small apartment in North Hollywood.

With his earnings from PestCal Exterminators, he saved enough to buy a place in Panorama City. It was a townhouse with high ceilings — something he had always wanted — and big enough for his growing family.

On top of covering most household expenses and the mortgage, he took care of the girls, efficiently dispatching the morning routine after Sanchez left early for work. He spoiled them with a snack or toy from the dollar store nearly every day.

In Los Angeles County, there is little mystery to the heaviest spread of the coronavirus. Where crowded housing is worst, the COVID-19 pandemic hits hardest.

After taking bereavement leave, Sanchez returned to her job at a medical device manufacturing company. She had been looking forward to going back to school and obtaining her degree in sociology once Ayala became a full-fledged barber.

“We were barely getting back [the benefits of] the hard work,” she said.

Ayala’s children — Janelly and Melanie, both 10, Leanna, 7, and Sergio, 2 — are too young to understand all the ways their lives will be different as they grow older.

But late at night, Sanchez said, the girls lie awake and cry to God: “Why him? Why couldn’t it be someone else?”

For 23-year-old Brianna Trejo, life has changed drastically since her parents, Cindy and Ruben Trejo, died of COVID-19.

She lived in an Inglewood apartment with them, her grandmother and an aunt while studying anthropology at Los Angeles Southwest College.

Her father worked with mental health patients and her mother was in hospital administration. Together, her parents paid the bulk of rent and bills for the household.

Her parents were planning to buy a house in the next year, maybe in Arizona or Nevada. Trejo wanted to transfer to a four-year college.

Ruben, 51, died on Jan. 12. Cindy, 47, died the next day. Ruben had received his first dose of the vaccine days before.

Brianna, her aunt and grandma still live in the same apartment, and they’ve all stepped up to cover expenses. She’s learning how to build her credit score and is cutting out luxuries, like the family Netflix subscription.

She is beginning to feel pressure to move forward with her life and secure a job, but her grief hasn’t been kind. In class, she sometimes zoned out, thinking about all the things she needed to get in order at home.

In August, she took a break from school to focus on her mental health. She is applying for administrative jobs but has yet to land one.

“They were really the ones who figured out how to balance all the bills,” she said of her parents. “That’s what I have to take on now. I have had to grow up within a year’s time.”

Researchers have long observed a phenomenon known as the Latino paradox. The average Latino life expectancy is longer than for white people, despite poor access to healthcare and higher rates of poverty and diabetes.

“It has hit us hard, especially because he was so young and he had a lot going for himself. He was working to do a lot more things that he didn’t get to do.”

— Nidia Campos

So many Latinos have died young of COVID-19 that researchers are wondering whether the paradox will hold.

Collectively, Latinos in California have lost about 370,000 years of potential life to COVID-19 as of Dec. 1, UCLA biostatistics researcher Jay Xu said.

Younger Latinos’ vulnerability to COVID-19 stems from a confluence of socioeconomic and health factors, researchers believe.

Lack of health insurance, or poor coverage with high copays, may lead people to delay going to the hospital, increasing the potential for a severe and deadly case, said Rita Hamad, associate director of the UC San Francisco Center for Health Equity.

Latinos are more likely to live in overcrowded and multigenerational housing with older immigrant relatives, have poor access to healthcare and work in essential industries that require them to show up in person.

Many essential workers — cashiers, truck drivers, meat packers — are Latino. They can’t stay home. And they’re being hit hard by the novel coronavirus.

They also are more likely to live in heavily polluted neighborhoods and have higher rates of diabetes, hypertension and obesity — conditions associated with severe cases of COVID-19, researchers said.

Latinos have the lowest vaccination rate of any demographic statewide, with younger Latinos particularly lagging.

The reasons include misinformation on social media and inflexible work schedules that leave little time for an appointment. Public health experts and community advocates are trying to get the word out to Latinos that they need the shot, especially because they have already lost so much to the virus.

The ripple effects of each death are profound. Some younger Latinos were providing for several generations of their families, both here and abroad.

Every two weeks, 38-year-old Jorge Ortega got off work as a delivery driver, sometimes at midnight, and made the three-hour drive to Tijuana to see his girlfriend, Viviana Seguro Gaitan, and their newborn son.

In their 48 hours together, the couple would savor every moment, even when just sitting on their couch watching movies all day.

Vaccination rates are up, but there’s fear Black and Latino men will continue waiting until they almost die from COVID-19 or watch people they know die before getting vaccinated.

When the weekend was over, Ortega drove back to Los Angeles early Monday mornings in time for work.

After a 12-hour shift, he went to his L.A. apartment where he lived with his mother, Yolanda Ortega, and his 14-year-old son.

In both homes, Ortega paid rent and bought groceries and other necessities for the two most important women in his life.

In January, Ortega died suddenly from COVID-19. As with Ayala and the Trejos, vaccines were not yet widely available for his age group.

“He wanted to start the legal process to become a U.S. citizen,” said Seguro Gaitan, 38. “We were going to get married and move in together. We were going to buy a house. For the kids.”

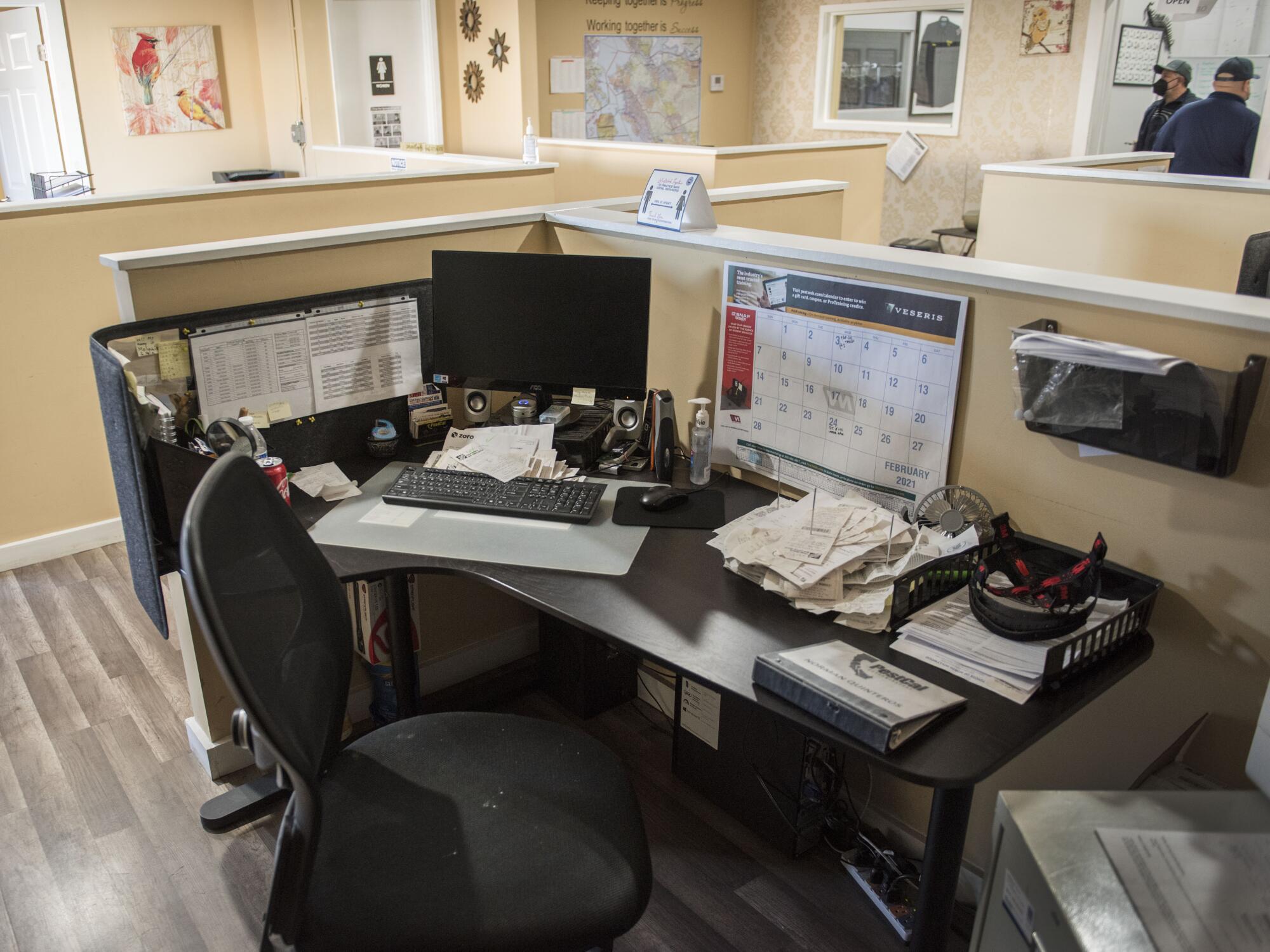

In PestCal’s North Hollywood office, Ayala’s presence is still felt.

A month after his death, his corner cubicle was cluttered with his belongings, including a message from one of his daughters scrawled on a yellow Post-it note: “Hi, my name is Melanie Ayala.”

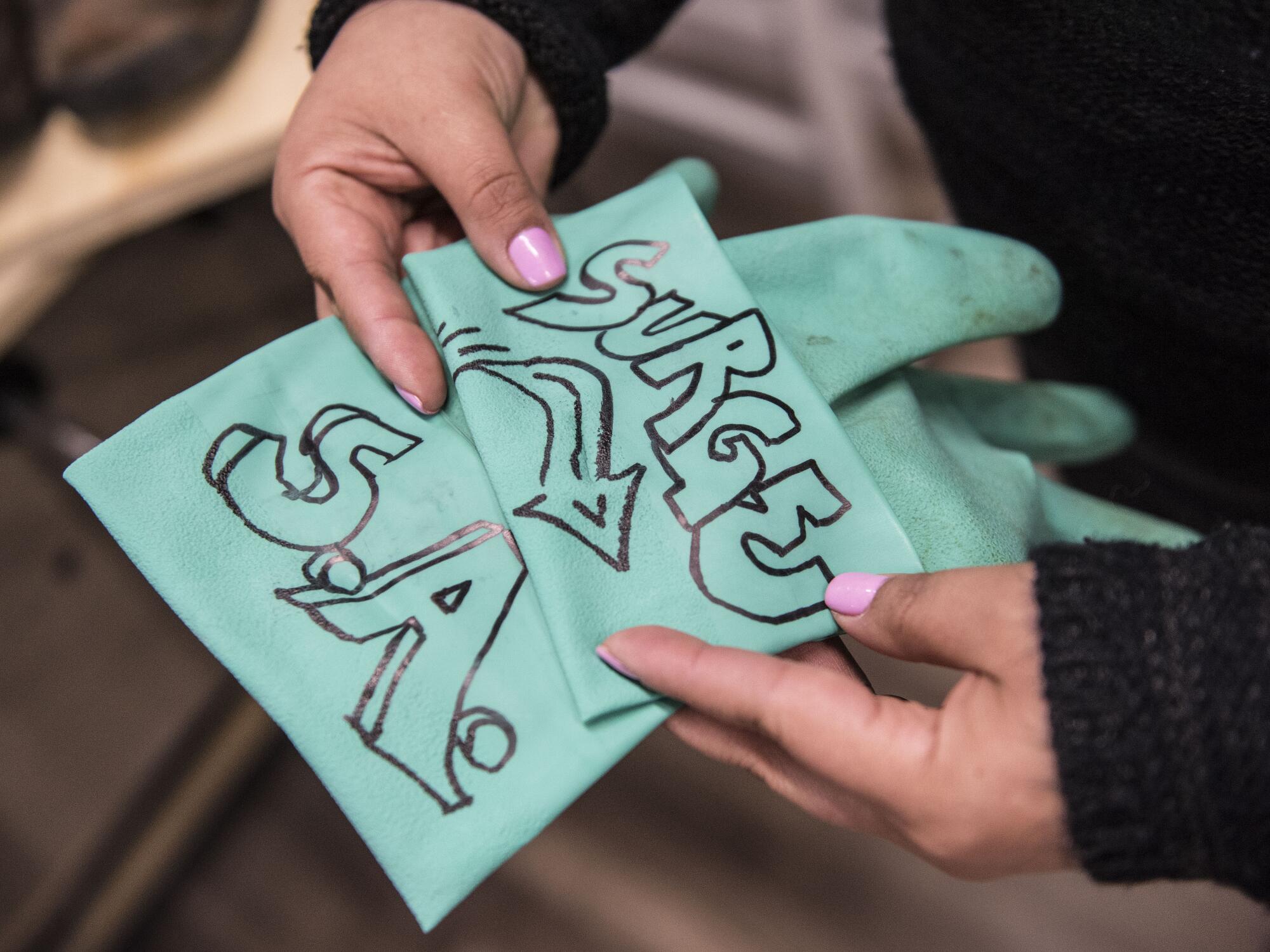

His work boots and green latex gloves, inscribed with his nickname, “Surge,” in graffiti-style letters, were perched on top of a shed.

In the break room, Ayala’s brother-in-law, Kevin Campos, gazed at a memorial portrait, a yellow halo hovering over Ayala’s head.

After the 2008 recession, Campos recruited Ayala to help him start PestCal. The two men often got doors slammed in their faces as they recruited customers, Campos recalled.

Before he became aware of his brother-in-law’s haircutting dreams, he had planned on giving Ayala a branch of the company.

Campos keeps a straight face and lighthearted tone in the office. He wants to be a rock for his family.

He thinks about what would happen to his wife and son if he were to suddenly die. He has beefed up his life insurance plan and retirement portfolio, just in case. Sometimes, he ducks into a room alone so they won’t see him cry.

Ayala’s children often spend weekends with Campos and his family. His wife, Nidia Campos, is Ayala’s sister.

“It has hit us hard, especially because he was so young and he had a lot going for himself,” she said. “He was working to do a lot more things that he didn’t get to do.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.