COVID-19 deaths top 100,000 in California: ‘Nobody ... anticipated this toll’

It was three years ago this month that California documented its first known victim of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now, the pandemic’s toll has breached a once-unthinkable level, with more than 100,000 deaths reported statewide, according to the California Department of Public Health.

Unlike the first known victim — whose tragic brush with the coronavirus was recounted in detail during the pandemic’s early days — we may never know the identity of the individual who represents the latest grim milestone in an era marked with them.

“The heartache of having so many people die weighs heavily on all of us here at public health,” Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said. “I think it weighs equally heavily on everybody who lives in our county, in our state and our country and the world. Nobody, I think, anticipated this toll. None of us wanted this to lead to so many people losing their lives, and it creates great sadness. It’s hard for our community to recover.”

Despite the massive number, newly reported infections have declined and stabilized in recent weeks.

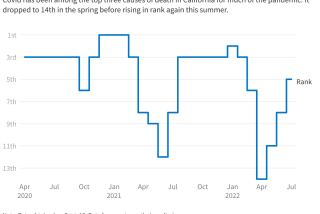

Even in a time of plentiful vaccines and therapeutics, when COVID-19 has been pushed to the back of many a mind, California is still tallying more than 20 deaths every day, on average.

And as the state enters what officials characterize as a new phase of the pandemic, the virus’ cumulative devastation remains hard to comprehend while its day-to-day effects are, for many, increasingly easy to ignore.

“Some people say it’s nothing, ‘Why are you bothering us with this pandemic? We should be back to normal now,’” Dr. Sylvie Briand, director of epidemic and pandemic prevention and preparedness at the World Health Organization, said during a recent webinar. “And others say it’s catastrophic: ‘My neighbor died yesterday. And last month it was my great-uncle who died.’

“Who is right?” she said. “Both perspectives are understandable because the risk of getting sick, the risk of having severe disease, is variable.”

California, the nation’s most populous state, has reported more COVID-19 deaths than any other. Texas, Florida, New York and Pennsylvania are the next closest, according to data compiled by The Times.

For perspective, California’s cumulative death toll is roughly equivalent to the population of cities such as Hesperia in San Bernardino County or Vista in San Diego County.

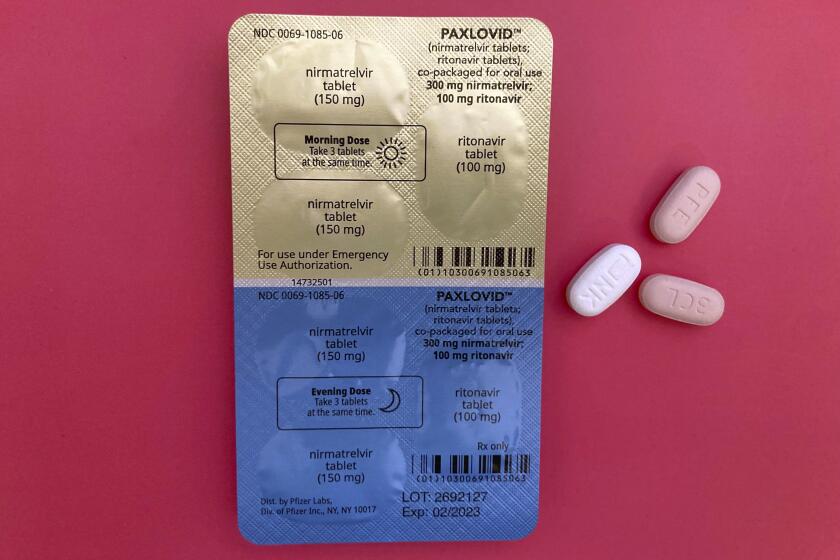

A pandemic allows the Food and Drug Administration to authorize vaccines and drugs for emergency use, even after the health emergency ends.

“This milestone is a tragic reminder of the very real toll the pandemic has taken on Californians,” the state Department of Public Health wrote in a statement to The Times. “Our focus remains on the steps we can continue taking to limit further loss of life due to COVID-19.”

L.A. County, the nation’s most populous county, has reported more than 35,000 COVID-19 deaths.

“Just the magnitude of that is unimaginable, except for the people who have to live with it,” Ferrer said. “And for them, we continue to keep you in our prayers and our thoughts.”

Despite the massive tally, the Golden State has the 11th-lowest death rate among states when accounting for population, 255.3 per 100,000 residents, according to data compiled by The Times.

By comparison, 10 states — Arizona, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Tennessee, West Virginia, Arkansas, New Mexico, Alabama, Michigan and Florida — have cumulative death rates of at least 416 per 100,000 residents.

For many now, life in California goes on much as it did before the pandemic. Businesses are open, concerts and sporting events are packed, and masks are increasingly a relic of the past.

“With this last surge this past winter, the numbers were much, much lower than in prior surges as far as hospitalizations, ICU and deaths,” said California state epidemiologist Dr. Erica Pan.

Still, the virus has already killed more than 2,200 Californians this year, with an average of 22 deaths per day tallied over the latest reporting period, state data show.

And even during this winter, easily the mildest of the pandemic era, the peak per capita death rate for COVID-19 has been “still much, much higher than a serious flu season,” Pan said during an online forum last week.

The pandemic took a harsh toll on U.S. teen girls’ mental health, with almost 60% reporting feelings of persistent sadness or hopelessness

The virus’ potency has been lessened through widespread immunity, either from vaccines, prior infection or a combination of the two. The availability of therapeutics and well-known health measures to tamp down transmission — including regular hand washing, testing and, in certain situations, masking — also have played a role in curbing COVID-19, officials and experts say.

“COVID-19 hospitalizations and death rates have dramatically slowed over the last 12 months because of Californians’ diligence in getting vaccinated and the sacrifices of all Californians to follow prevention and treatment guidance and tools,” the state public health department said. “Overall, through the state’s collective efforts, California has one of the nation’s lowest COVID-19 death rates compared to other states of comparable population sizes.”

But the danger is not the same for everyone. According to health officials, older adults, people with chronic health conditions and those who are unvaccinated are among the individuals who remain at increased risk for severe COVID-19 illness and death.

In December, unvaccinated Californians were 2.4 times more likely to contract COVID-19 than those who had received at least their primary vaccine series, state health data show. Unvaccinated residents were also 2.6 times more likely to be hospitalized and three times more likely to die from the disease.

“We know from our information, from the data we’ve been collecting, who’s at higher risk,” Ferrer said. “Our job is to make sure that, collectively, we recognize that there are some people that have much higher risk and we do our very best together to try to enhance their protection.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.