From the Archives: Reclusive writer Eve Babitz is suddenly the toast of L.A.

This story was originally published in October 2019. Iconic Los Angeles writer Eve Babitz died Friday at 78.

In the dedication to her first book, “Eve’s Hollywood,” Eve Babitz dryly thanked Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne for “having to be who I’m not.”

The “Didion-Dunnes,” as she referred to them, were friends of Babitz’s and in her social orbit when the book was published in 1974, but the line is also clearly a burn. (And a bit of self-own — but that was Babitz’s light brilliance, to playfully cast herself as both charming foil and punchline.)

For Eve Babitz — whose resurgence reached its zenith Tuesday with the publication of her first “new” work in decades — was, quite accurately, everything the Didion-Dunnes were not.

If Eve Babitz were to have worn an old bikini grocery shopping to the Ralphs on Sunset and Fuller in the late 1960s, it would have been for fun, spectacle and seduction purposes — not because the center couldn’t hold.

Babitz was dishy where Didion was coolly detached, as well as lusty, seemingly unserious and somewhat of a pleasure-seeking missile.

The daughter of a Twentieth Century Fox Orchestra violinist, she was raised at the base of the Hollywood hills amid haute bohemians and film royalty. The young Babitz was beautiful, brazen and at home in high culture: “I looked like Brigitte Bardot and I was Stravinsky’s goddaughter,” as she put it in her first book.

She gained notoriety just a year or two out of Hollywood High for posing nude at a chess table opposite Marcel Duchamp in 1963. The picture was meant to exact revenge on her married boyfriend, but it would become a defining image of the burgeoning West Coast art scene.

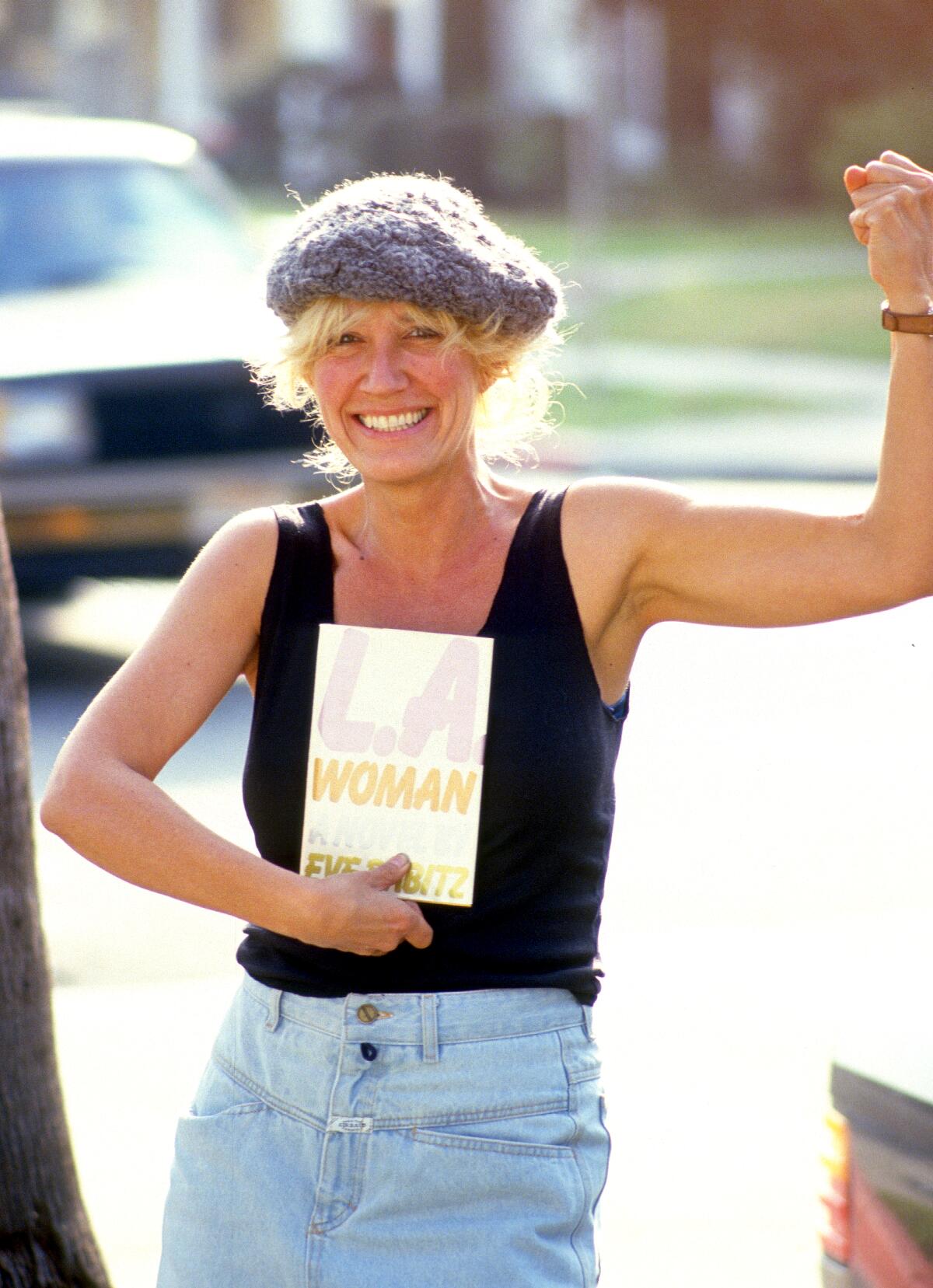

Eve Babitz, who chronicled life in Los Angeles with a hedonistic zeal drawing from lived experience, found her truest literary fame late in life.

She remained an art and literary world “It” girl in the 1960s and ’70s, gallivanting about town with a Zelig-like ability to both befriend and bed cultural figures. Her big writing break came in 1971, when she published an essay in Rolling Stone after Didion passed it along it to the editor. “Eve’s Hollywood” was published in 1974, and several other books followed.

But in 1997, Babitz retreated from public life after a freak accident. She was departing a Sunday brunch in her old VW bug when she struck a match to light a little cherry-flavored cigar. The lit match fell and ignited her gauzy skirt like something out of a nightmare. Babitz was left with third-degree burns across nearly half her body, and deeply in debt from the ensuing medical treatment. And then she all but disappeared.

The current Babitz renaissance began in earnest in 2014, when the septuagenarian recluse was the reluctant subject of a Vanity Fair love letter-cum-magazine profile written by Lili Anolik. At the time, Babitz — who had not been taken particularly seriously by the literary establishment to begin with — was largely forgotten, with her books dusty and out of print.

A wave of renewed interest in her work followed, with the New York Review of Books Classics reissuing two of her books, starting in 2015 with “Eve’s Hollywood,” followed by “Slow Days, Fast Company.” Counterpoint Press reissued several others.

Anolik’s obsessive pursuit of Babitz and her legacy culminated with the publication of “Hollywood’s Eve: Eve Babitz and the Secret History of L.A.” in January 2019, which pronounced Babitz as “the louche, wayward, headlong, hidden genius of Los Angeles.” Anolik’s book is more adulatory valentine than straight biography, but the breezy infatuation is perhaps befitting of its subject and the lush exuberance of her work. Babitz never hid her excitement, and nor does Anolik.

Writer Brian Moore once said that despite its criticisms, Los Angeles is never provincial: “People in Southern California never look anywhere else in the world for instructions about what to think or how to behave.”

In her heyday, Babitz had often been written off as an insubstantial party girl — as famous for her decolletage (legendary) and her conquests (also legendary) as her work.

The New York Times declared “Slow Days, Fast Company” to be “a mixture of the beguiling and idiotic, tossed in a light dressing” when it was first published in 1977; “Sex and Rage,” this paper exclaimed in 1979, was “an extended example of women’s magazine fiction at its most mediocre.”

But after decades of obscurity — and even as Babitz herself remained in relative seclusion — her name and books were suddenly everywhere toward the end of the current decade.

Or at least “everywhere” within an extremely specific subset of the world, as the New York Times breathlessly revisited her work, Hulu developed a series based on her books, and millennial cool girls the internet over posed with her reissued book covers on Instagram.

Yes, Babitz nazel-gazed and name-dropped, but she was also an exquisite observer of the city and her very specific cultural milieu. Was her Los Angeles a delirious, languid playscape made possible — as critics have accused — by her looks, privilege and access?

Why, of course. That’s why it’s fun to read.

She may have been young and beautiful in the era of “Eve’s Hollywood,” but she also keenly understood and observed the quicksilver currency of each thing, and knew how to channel them to her own ends. A woman can be both frothy and shrewd.

But in a city of sunshine and noir, there is a certain pro forma equation we’ve come to expect from literary depictions of the easy glamour and glaring light. They should only be introduced as a contrast to the darkness, with every fun party scene adding up to ultimate damnation. It’s fine to dab a bit of shimmery paint, as long as the canvas in question eventually reveals the gaping void — and the view from the beautiful house in the hills makes clear that this is Sodom and Gomorrah. Except that Babitz’s work refused to embrace such a well-trodden binary.

While I may quibble strongly with Anolik’s categorization of “Slow Days” as a superior book to Didion’s iconic L.A. novel “Play It as It Lays,” I can’t disagree with her assertion that “Play It as It Lays” flatters the reader and tells us what we already presume to know — that, as Anolik writes, “Hollywood is rotten and corrupt; the that the beautiful people have ugly souls; that the game is rigged.”

But “Slow Days,” Anolik argues, with “its total lack of interest in approving or disapproving of its characters’ morals,” has, in its own way, too much amused skepticism to emerge with such an easily quantifiable calculation of darkness and light.

Anolik, who had drawn an earlier parallel between “Play It As It Lays” and “The Day of the Locust,” was also, by extension, comparing “Slow Days” to Nathanael West’s L.A. damnation opus, which Babitz famously hated. (She thought it was simplistic, and that West — in his refusal to be seduced — missed the flourishing splendor of the place, so that, as she put it, “the bougainvilleas didn’t stand a chance.”)

The essay where Babitz takes on West is from her sometimes messy first book “Eve’s Hollywood,” but there is nothing meandering about this section: “People from the East all like Nathanael West because he shows them it’s not all blue skies and pink sunsets, so they don’t to worry: It’s shallow, corrupt and ugly,” Babitz writes, with the worry in question presumably being that while back there it is winter, out here the bougainvillea remains eternally in bloom.

In Babitz’s slyly witty view, “The Day of the Locust” — that essential novel of the L.A. literary canon — is really just one chump’s attempt to assure his buddies back east “that even though he’d gone to Hollywood, he had not gone Hollywood.” It is, as she puts it, a “little apologia” for West taking that dirty Hollywood money and basking in the sun. Or a man managing to have his cake and eat it to.

And maybe that, more precisely, was what was so off-putting and seemingly unserious about Babitz in her day. She wanted to have her cake and eat it to, to write the story and also star in it. But without any of the requisite nothing-matters remove to apologize for the shiny parts.

There is a specific brand of brittle, damaged delicacy that we’ve come to revere in women writers who describe their own insular lives and also look striking in their author photos. Babitz was messy and certainly at times adrift, but she was having far too good a time for the rest of it.

Her work, even the ostensible fiction, was always autobiographical, and ironically, it’s likely the writer’s later biographical arc that has finally allowed for the imprimatur of importance. After all, disfiguring accidents, J.D. Salinger-like disavowals of public life and the simmering cult interest of writers and scholars are typically the province of Serious Literary Figures, not flibbertigibbets and fun L.A. “It” girls.

“I Used to Be Charming,” which was released by NYRB Classics on Tuesday, contains nearly 50 previously uncollected pieces written between 1975 to 1997. It includes a searing piece on her accident and lengthy recovery that begins with a passage about her setting the side of a hill on fire as she, skirt aflame, tries to roll on the grass to get the flames off her. All while a nice “Sunday-brunch couple” look on in horror.

“The thing is, this wasn’t the first time I had been nakedly embarrassed in Pasadena,” she writes, referencing her famous au naturel chess match with Duchamp at the Pasadena Art Museum.

Except now the carelessness carries the weight of a comeuppance, and the craving for beauty and fame comes at a cost. And that’s an L.A. narrative we know how to categorize.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.