Presidential visits trace L.A. history from small town to big-money donors

You know what they say: You can’t spell “Los Angeles” without “A-T-M”!

Kidding. Nobody says that. Yet whenever presidents look at Southern California, they certainly spell “Los Angeles” with dollar signs.

Americans are supposed to be thinking about presidents on Presidents Day. But how do presidents think of us — specifically, the Southern California us?

Three words pretty much sum up the chiefest reasons for chief executives’ pilgrimages here: gold, glory and golf.

The glory part has pretty much gone the way of the presidential yacht, which is to say, it’s a ship that has sailed. There was, once upon a time, a time when a presidential visit to L.A. did not send annoyed Angelenos to their GPS devices to plan their way around presidential motorcades’ rolling ramp shutdowns and ripple-effect gridlock. Instead, it sent them into the streets to cheer.

Well before the second world war, when Los Angeles was still civically insecure and tetchily provincial, sitting presidents were welcomed with singing schoolchildren and symbolic keys and citrus and bouquets and long proclamations. The parades were monumental in scale and turnout.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

The enormous acclaim makes even more sense because L.A. was a Republican town, and the first five presidents to visit were too, including William Howard Taft, a literally enormous Republican who had special chairs made for his stops here and in Riverside.

About 5,000 people lived here in 1880 when Rutherford B. Hayes became the first president to visit the West Coast. His visit was to be a kind of national emollient after his 1876 victory, which was notable for its brutal and not-altogether-above-board backroom bargaining over electoral votes, hence the nickname “Rutherfraud” Hayes. The City Council was so over the moon that it appropriated $25 (that’s almost $700 now) for an eight-course banquet in his honor.

The Hayeses took in a livestock show at the present Exposition Park and swung by the San Gabriel Mission, and Mrs. Hayes stopped in Pasadena to see the house where her brother had once lived — all of it probably quite the anticlimax after the beauty places on their “Great Western Tour,” like the Columbia River, the Rockies and Yosemite.

Maybe Hayes left behind some notes about L.A. for his successors, because another president didn’t visit until 1891.

Benjamin Harrison got the full treatment — a “president’s special” locomotive draped in bunting and flowers, and L.A.’s creme de la creme so anxious to get in on the glory that they boarded his train miles outside of town, accompanied the rest of the way, in both senses of the word, by a strumming quartet from the Los Angeles Mandolin Club.

What raised a fuss in the press was whether the president had drunk wine at a Pasadena hotel. Considering that the waiters had started knocking back the official Champagne long before Harrison arrived, and were so squiffy that they wound up serving dessert first, there may not have been much left for Harrison to drink anyway.

It’s in the stories about Harrison’s visit that you find the kind of absurd moments that presidents are expected to enjoy. On his way here, Harrison was persuaded to stop in Riverside to pose alongside a towering Lego-like stack of the first locally commercially produced bars of tin. On Harrison’s way out of town, in Santa Paula, eager locals clambered aboard his train to present him with a 5-foot-tall model of an oil derrick, made entirely of flowers. A year after his California visit, Harrison created what we now know as Angeles National Forest, which must prove there were no hard feelings.

The man who may have attracted the biggest crowds was the first sitting Democratic president to show up here. Woodrow Wilson in 1919 was fresh off his triumphs at the Paris peace conference, so his visit was poised between glory and tragedy.

His welcome parade rolled through 10 miles of town. A to-the-rafters crowd of 7,000 heard him speak passionately about the League of Nations at the Shrine Auditorium. An additional 50,000 — this per The Times — tried to get in but were turned away. The man who had reshaped the postwar world at Versailles spent his L.A. nights in the 43-room Imperial Suite at the Alexandria Hotel.

Five days after Wilson left L.A., he was in Pueblo, Colo., where he collapsed, and a week later, back in Washington, D.C., a stroke nearly killed him and certainly killed what remained of his presidency.

(So that’s Wilson. William McKinley was assassinated four months after his L.A. visit. President Warren Harding was on his way here in 1923 when he died in San Francisco. Just sayin’ ...)

When Republican President William Howard Taft came in 1909, he was shown the pride of the Chamber of Commerce, which was then an agency so powerful it functioned as another branch of government. It was a life-sized elephant, made entirely of California walnuts. His hosts waited for his astonished reaction. “Well!” Taft exclaimed. Then he described the sight with a nicely fluid word that can mean exactly what the hearer wishes it to mean: “unique.”

The Times made ungallant references to Taft’s heft, and to the chief reason for his visit, to see his sister. She lived in Pasadena and joined her brother aboard the presidential train car. “Though Mr. Taft weighs 300 pounds or more, his sister is of ordinary weight for her stature.” Meow.

Otherwise, Taft rolled around L.A. in an open automobile covered with yellow chrysanthemums as big as grapefruit, and at Polytechnic High on Washington Boulevard, he was handed a spade to break ground on a new art building. “I am loath to confess my ignorance in the study of art.” That, and two shovelsful of dirt, was about all he could manage, in spite of a student yelling, “Dig it deeper!”

Moviemakers, painters and authors have long opined on the quality of L.A.’s light. A Caltech scientist illuminates on why our light is so remarkable.

Both Taft and McKinley made a visit — a pilgrimage, really — to the gingerbread-styled Soldiers Home that still stands in the middle of the vast VA grounds in West L.A. McKinley’s visit, in May 1901, probably got the most ink in The Times, for the plain reason that Times publisher and fellow Ohioan Harrison Gray Otis had fought in McKinley’s regiment in the Civil War. When the Spanish-American War erupted, Otis wangled a brigadier general appointment from now-commander in chief McKinley, and returned from the Philippines as a major general. It was a title he used the rest of his life, and embellished by giving brusque military names to his property, like calling his home “the Bivouac,” where he hosted a reception for McKinley.

The McKinleys stayed at the Van Nuys Hotel, at Fourth and Main, and from a balcony of his suite, McKinley spoke the sort of words that host cities thrill to hear, in this case something that now sounds like an unkindly reference to the Philippines and Cuba: “They say liberty does not thrive under a tropical sun. Did liberty ever thrive more grandly than in the state of California and throughout our southland?”

A few years thereafter, Taft complimented his Pasadena hosts more adroitly with the tweak on Julius Caesar’s prose, “I came, I saw, I am conquered.”

Teddy Roosevelt, who became president after McKinley’s assassination, arrived in 1903 “unshaven and travel dusty” and scorning dress duds for a banquet in his honor. His civic speech made mention of two of his favorite topics, irrigation and the Navy, but for this polymath president, everything was a favorite topic.

The Arroyo Seco thrilled him; on its banks, he would visit the river-stone home of his old Harvard buddy Charles Lummis. Once he got a look at the Arroyo Seco, in 1911, TR admonished us never to change it. “This arroyo would make one of the greatest parks in the world.” It is now the Pasadena Freeway, and we certainly do a lot of reluctant parking there.

The second President Roosevelt, Franklin, campaigned here at the Hollywood Bowl, and a few days after FDR won, the newly made lame duck president Herbert Hoover rolled into town to visit his son in Sierra Madre.

As president, FDR motorcaded around the Coliseum floor in 1935, in Cecil B. DeMille’s car, whence he spoke to thousands there. In Griffith Park, he also unveiled a statue to Civilian Conservation Corps workers; 29 of them had been killed in a fire there two years before, as they worked on roads and maintenance. The statue, of a shirtless CCC worker, has disappeared. FDR returned secretly in September 1942, inspecting defense works like the Douglas aircraft plant in Long Beach, Camp Pendleton, and naval facilities in San Diego.

After the war you couldn’t keep the presidents away. Just like the settlers who swarmed the new-made suburbias, they wanted a piece of this sweet sunshine and that ever-bigger pile of electoral votes.

Harry Truman, the man from the Show-Me State, went showbiz in 1948. He made two L.A. stops during his campaign. In September, at Gilmore Stadium — where CBS Television City now stands — his warmup acts were a couple of couples, Lucy and Desi, and Bogie and Bacall — and another Hollywood light named Ronald Reagan. By 1961 Reagan had become a Republican, and the people’s choice, elected to the Topanga Soil Conservation District.

Truman didn’t let on in 1948, but in 1962, he was so put off by L.A. that he said, “I’m dressed, and packed up for the trip to the U.S. no. 1 ‘crackpot’ city.”

His successor, Dwight D. Eisenhower, liked the desert golf offerings just fine, buying a house in Palm Springs. President Gerald Ford found his own post-White House golf place in Rancho Mirage. As campaigner and president, Ike got some Hollywood love too, with Bob Hope and Jerry Lewis entertaining at the Hollywood Bowl on his behalf. The man who led the Allies to victory in World War II almost got conked during a ticker-tape parade in 1952, back when you could still open downtown high-rise windows. The ticker paper didn’t hurt him, but a muffler dropped off a car, flipped, and almost clocked the general in the head.

John F. Kennedy won the presidential nomination here, and one of the seminal photos of JFK’s presidency was taken on the Santa Monica beach. Kennedy took a plunge in front of the home of his actor brother-in-law, Peter Lawford, and was swarmed by fans who walked into the water fully clothed just to try to touch him as he waded out, wet and beefcakey.

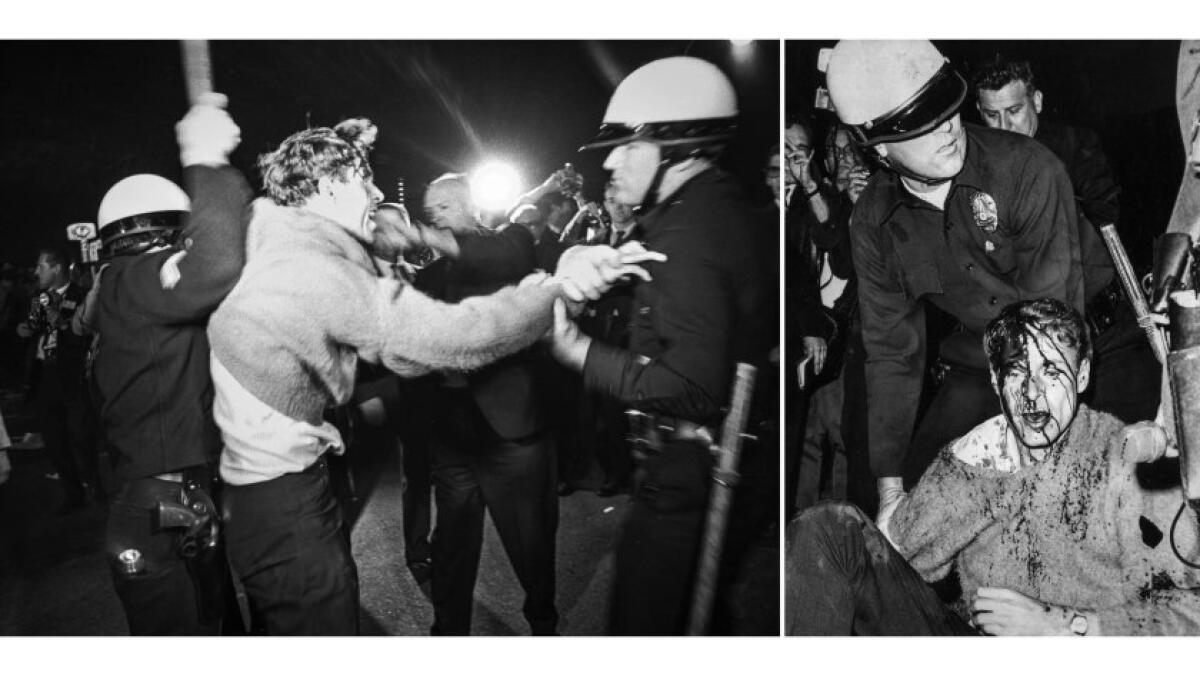

JFK’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, was here several times. One time, he never even left Air Force One, sitting on the phone as the plane sat on the tarmac at LAX. One time that he did venture forth, for a large fundraiser at the Century Plaza Hotel in Century City, a crowd of protesters against the Vietnam War grew into about 10,000.

Police waded in unprovoked and whacked a lot of middle-class voters, and the Secret Service thought it might have to pluck LBJ out of there by helicopter.

Same hotel, different protests, and more restrained police presence in 1979 for President Jimmy Carter. He had come here when his presidency was new, in 1977, to speak to the United Auto Workers convention. What made the biggest news was when Carter did not come to L.A. He bailed on a March 1979 Democratic Party fundraiser to be in D.C. for Mideast peace talks, but dissident California Democrats still planned to buy big newspaper ads to take Carter to task.

Carter had planned to spend a night with a Latino family in Montebello on that trip, but that got scrapped too. He did make it back for Cinco de Mayo, spending the night at Gloria and Stephen Rodriguez’s house in El Sereno. The couple slept in the den to let Carter have their bedroom. The president woke at 6 a.m. and jogged with his host to the track at Wilson High School — named for Woodrow Wilson — while Gloria Rodriguez fixed breakfast: tortillas, chorizo, refried beans, strawberries and milk.

Richard Nixon, the only California-born president, began and ended his political career here. Reagan, a Californian by choice, seemed more like a natural in the setting than Nixon, and ended his career and his life here.

George H.W. Bush, as vice president, campaigned here in 1988, submitting to a sombrero coronation at the farmers market.

As president, Bush visited Los Angeles to assess damage from the 1992 rioting roiling the city during the year of an election that he would lose. While he was here, as The Times noted, he dashed off to tennis so quickly one day that he briefly lost his Secret Service detail and the officer holding “the football,” the briefcase with the nuclear codes.

Bill Clinton, the baby-boomer president, loved L.A., visiting it at least a dozen times as president, showing up after the 1994 Northridge earthquake and the next year, more felicitously, at the House of Blues, grooving with Jim Belushi.

Only four months into his presidency, Clinton was on the back foot, denying that he had “gone Hollywood.” He had held up at least two LAX flights as he sat aboard “Hair Force One” for almost an hour, getting a haircut from a Beverly Hills stylist. It was not the kind of image that the man who bragged about his $40 watch had run on, nor one that he wanted to be stuck with.

With a ranch in Texas, George W. Bush didn’t need California for Western cred. He came to the San Diego area in 2007 to size up what the feds could do after catastrophic fires there. He made the usual fundraising rounds, to the snowballing presence of protesters. In 2005, the Republican governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, boycotted Bush at a GOP fundraiser. However often Bush visited, he never made a sentimental journey to a Compton apartment where his family lived for a few months in 1949 and ‘50, when little George was 4 and big George, his father, was selling oil drilling bits.

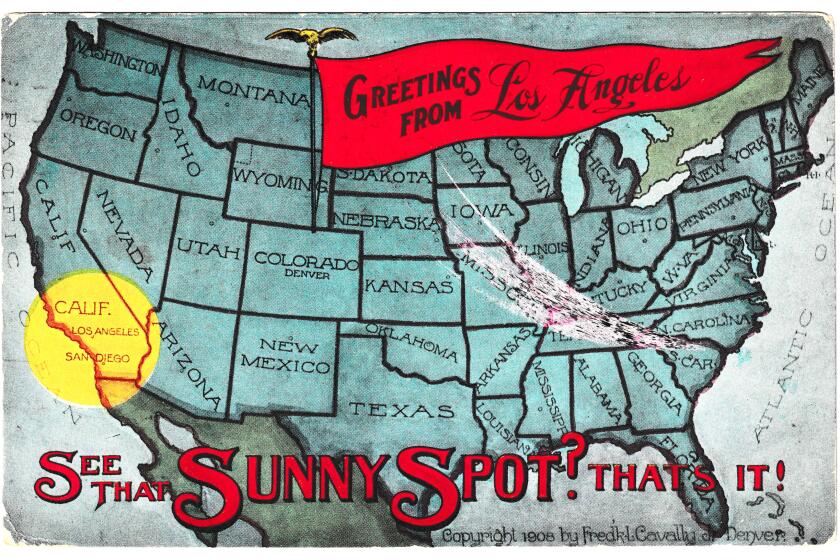

Sunny and mild L.A. winters have long been used to sell our town to frigid Midwesterners and Easterners, attracting the sick, the farmers and the moviemakers.

President Barack Obama loved L.A. and the place loved him back, giving him some of the biggest turnouts since the old pueblo days.

Donald Trump came here at least five times as president, to heftily profitable fundraisers. One was charging $100,000 for golf and a photo op, and a quarter-million if you wanted a round-table talk too. That kind of money was a tradeoff for the hostile protests that Trump encountered; beyond the private, gated fundraisers, the relationship between Trump and L.A. was pretty much one of mutual loathing.

In his first year in office, President Joe Biden has made it to California to be briefed on wildfires and to back Gavin Newsom against the recall. Expect more POTUS swings for the midterms.

So it’s clear that presidential drop-ins are no longer front-page news or occasions for parties. Today, it’s Southern California conferring the favors on the chief executives, not the other way around.

There is one president who desperately wanted to see California but never got to. Less than a month before his assassination, Abraham Lincoln told an old friend, then posted in California, “I have long desired to see California; the production of her gold mines has been a marvel to me, and her stand for the Union, her generous offerings to the Sanitary [Commission], and her loyal representatives have endeared your people to me; and nothing would give me more pleasure than a visit to the Pacific shore, and to say in person to your citizens, ‘God bless you for your devotion to the Union,’ but the unknown is before us. I may say, however, that I have it now in purpose when the [transcontinental] railroad is finished, to visit your wonderful state.”

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.