- Share via

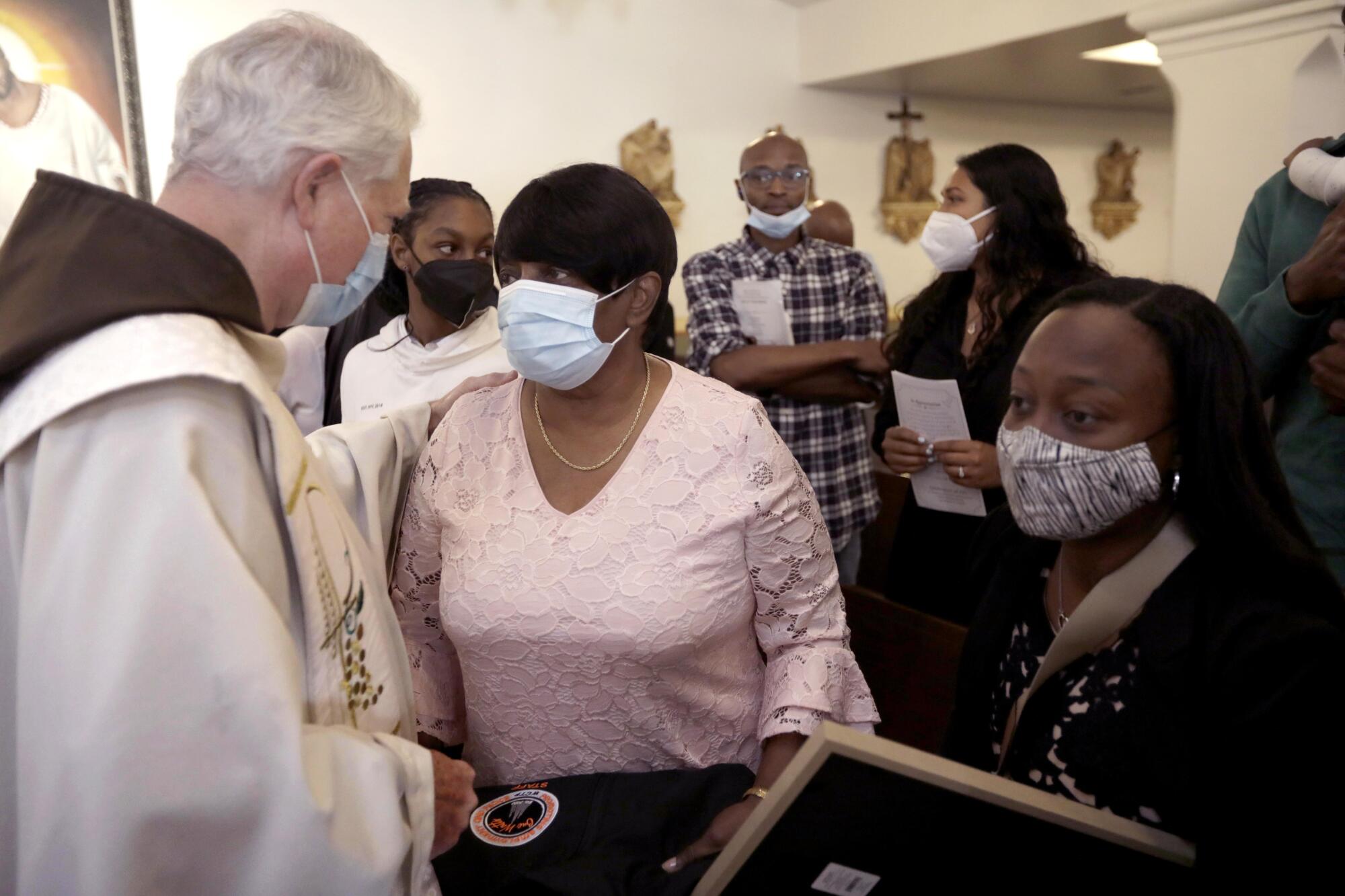

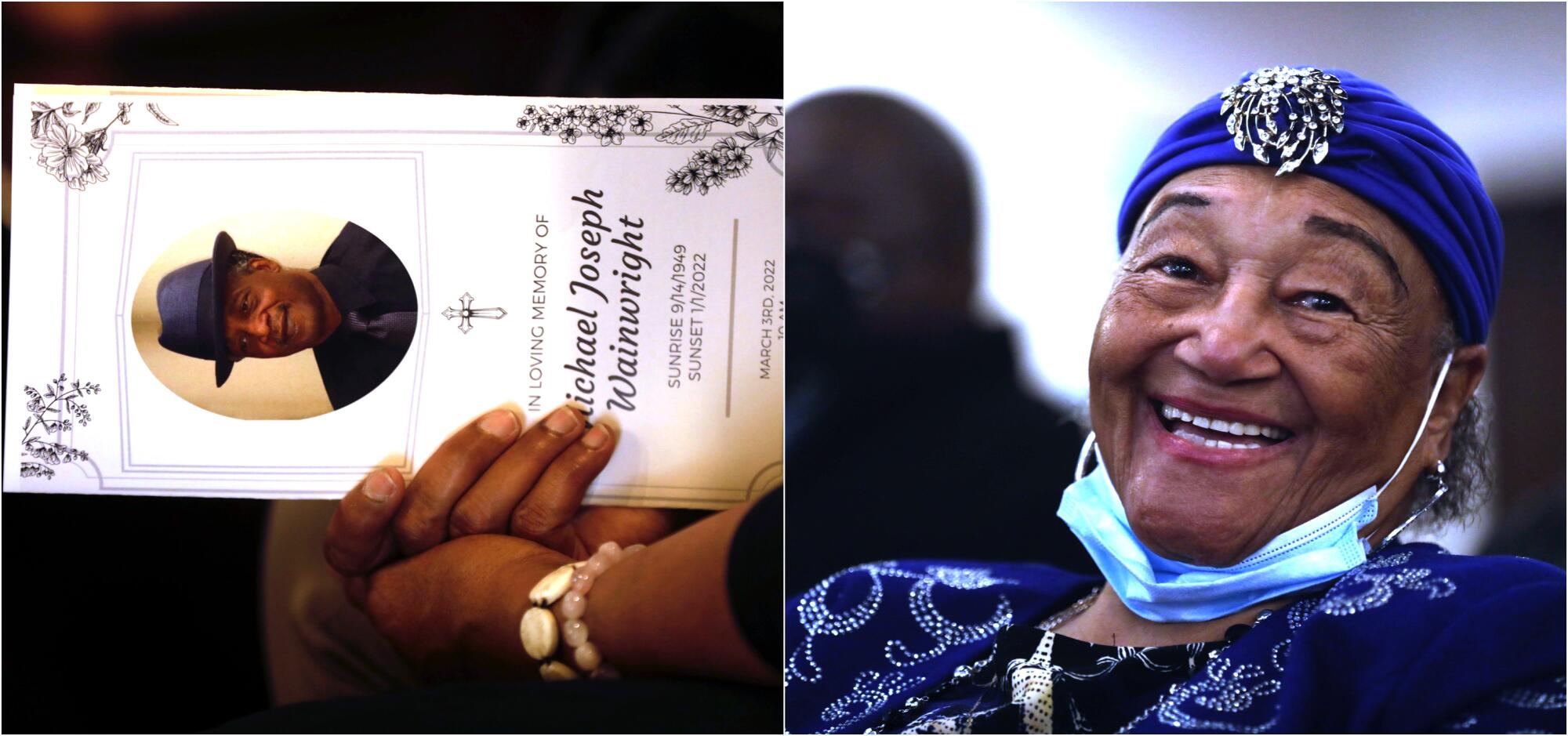

It was a funeral befitting Michael Wainwright’s legacy, held on a bright March morning in the shadow of a Watts housing project, at a century-old Catholic church that had nourished him through good times and bad. The liturgy was celebrated by a retired Irish priest who had shepherded Wainwright’s decades-long evolution. And the mourners in the pews were the beneficiaries of that journey.

There was Los Angeles County Supervisor Janice Hahn recalling how Wainwright upbraided her when she brought a spay-and-neuter van to a visit with her Watts constituents 15 years ago — as if pet birth control was the biggest problem in a neighborhood that had just endured an excruciatingly violent December. Wainwright strode over to yell at her: “The kids can’t even go outside and play with their Christmas presents! What are you doing about that?!” Two days later, they met in her office; the Watts Gang Task Force was conceived and a friendship was launched.

After Hahn gave her eulogy, former street gang members took the mic and shared how Wainwright had tricked, then cajoled, them into serving alongside LAPD officers on that task force, a partnership that rankled sensibilities on both sides, but paid big dividends on the streets. Those O.G.s became peacekeepers, and the task force, which still meets almost every week, led to investments in community policing that loosened crime’s grip on Watts.

Until Parkinson’s disease slowed him down in 2016, Wainwright had seemed unstoppable, a man of boundless energy and relentless positivity. He was bent on charting a path out of poverty for residents of Watts’ public housing projects, and he knew that began with education.

“There are those that talk about change,” wrote school teacher Traveon Cason, who graduated from Santa Clara University seven years ago thanks to a scholarship program Wainwright created. “And then there is Michael Wainwright, the guy that rolled up his sleeves seven days a week, to bring about change in his community.”

Wainwright taught young men and women in the projects more than how to study or what “business casual” means. “Michael planted a seed in me and many others that inspired us to move forward with enthusiastic hearts, and a clear sense of faith and integrity,” wrote Marques Dawson, a Cal State Long Beach grad and now a computer science engineer.

“If we’re lucky in life, we meet someone who teaches us just by existing. I was fortunate to have that in Michael.”

***

I met Wainwright in 2006, when I was reporting for a column on summer jobs programs and heard about his efforts to find jobs for kids from families where no one else was gainfully employed. He wanted to steer children away from trouble, toward college and on to professional careers.

I wrote about him and we stayed in touch over the years, as the list of young people he helped grew from dozens to hundreds.

Late last year, I’d begun interviewing his students to update that story when I learned that Wainwright was dying. He passed on Jan. 1; he was 72 years old. And I realized, when my tears wouldn’t stop, that I had come to love Wainwright too.

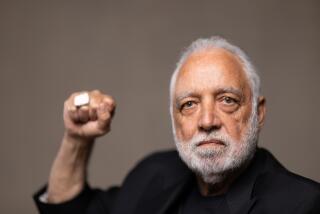

He was the kind of character who makes a good story: pushy, impatient and rough around the edges, despite his own middle-class upbringing and university degree.

And he also taught me just by existing: Mistakes will be made. Commitments must be kept. Never lose hope when you’re on the right track. His life reminded the journalist in me how pointless trying to pigeonhole someone can be.

Wainwright spent 15 years in the fog of drug addiction — and the next 20 years tirelessly serving his community. What kind of man does that make him? One who understood failure, believed in redemption and wasn’t afraid of a fight. From my vantage point, that was just what his proteges needed.

“Everybody in the community knew Wainwright, because he was the one you’d go for a summer job,”

— Sha’Ron Berry, who grew up across the street from Michael Wainwright

In the process of serving others, Wainwright was the author of his own restoration. And he never hesitated to remind me, “I’m a soldier, not a savior.” He was “paying the Lord back” for all those years he fell short.

***

Wainwright was jobless and living in Nickerson Gardens back in the 1990s, when he began holding reading classes and cleanup campaigns for children in the public housing project.

That led to a role running a federal summer youth employment program for low-income teens. He was so successful at badgering officials that he got hundreds of job slots over the years and schooled jaded teens in what work ethic means.

“Everybody in the community knew Wainwright, because he was the one you’d go for a summer job,” recalled Sha’Ron Berry, who grew up across the street from him and had a job every summer during high school.

When the jobs program ended after four years, Wainwright launched a college readiness program he named Neighborhood Youth Achievers. It included daylong Saturday classes on the “life skills” needed to navigate the world beyond Watts.

The teenagers grumbled about that, but they kept showing up. Berry remembers her mother walking her to class every week, along a route that took them through rival gang territories.

The program gave dispirited teens permission to dream. In their world, the only lucrative careers involved thieving or dealing drugs. Under Wainwright’s tutelage, they saw new possibilities. A good education could propel them beyond the projects’ dreary confines, into respectable jobs and comfortable lives.

“He understood the kids in the community,” Berry told me. So much had seemed off-limits for them, for so long. “He knew we needed a little more hand-holding.”

Berry knew that she wanted to go to college; she had her heart set on San Jose State. But when she saw the price tag, she gave up. “It was $20,000,” she recalled. “That was nothing my family could ever afford.”

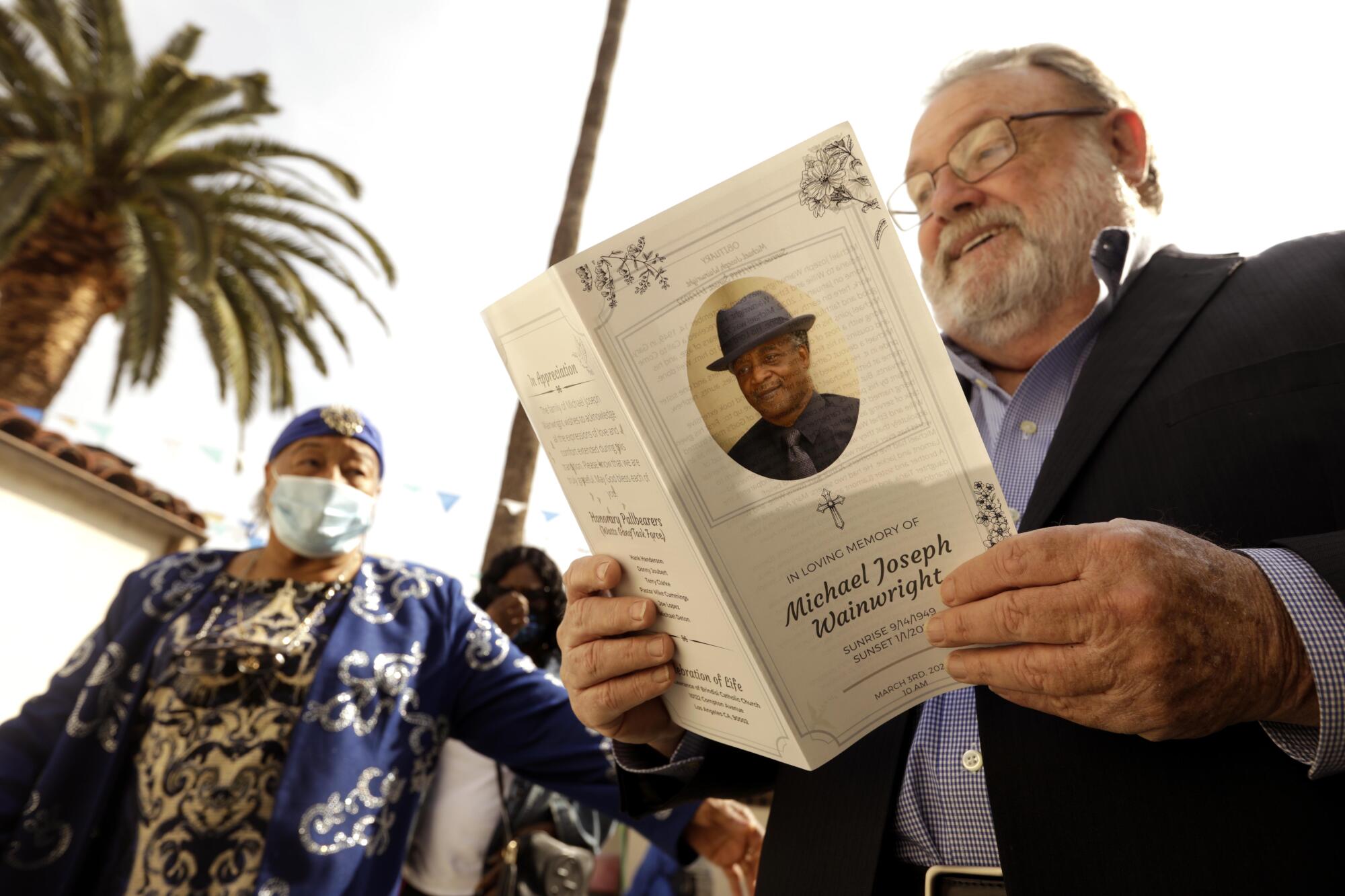

Enter Wainwright, the bridge builder. He reached out to his friend John Martin, a retired businessman with his own pipeline for getting poor kids into good Catholic schools.

He and Wainwright were an unlikely duo, but they shared the same family values and deep religious faith — and they understood their roles. Wainwright was the driver, and Martin the fuel.

“Mr. Martin was this white, white, white guy who was comfortably walking around the projects, looking for kids,” Berry recalled, chuckling at the incongruity. “He would listen to me and let me vent about my problems. And the next time, he’d come back with some kind of solution.”

There was a lesson in that: You can’t judge a book by its cover.

Back then Berry was not exactly a star student. Her father was absent, her brother was in jail and she was focused on helping her mother keep the family afloat. From time to time, they were so broke they had to live in their car. Her studies suffered because of the instability.

“These were things I was embarrassed about,” she told me. “I didn’t want to open up to anybody… But Wainwright didn’t give up on me. He told me to join NYA, go to classes every Saturday and stay out of trouble.” And he suggested she tell her family’s story in her college application essay.

That was another Wainwright lesson: You can’t move forward until you come to grips with your past.

That fall, Berry was college bound; on her way to New York with plane tickets Martin had paid for, luggage he provided and a full scholarship to Marist College, where the president was an alumnus of Martin’s Catholic high school alma mater.

Four years later, in 2013, Berry graduated from Marist with a finance degree. Today Berry is the senior executive assistant to the CEO of the South Bay Workforce Investment Board, helping other people prepare for and plot their careers.

In the 15 years since Berry was in those Saturday classes, Neighborhood Youth Achievers has sent almost 150 students to universities all across the country. Martin calls them “the nuggets that get overlooked.” Today they are teachers, tech gurus, money managers, artists, entrepreneurs. Several are working for nonprofits, and others serve on the NYA board. Many have done well enough to move their entire families out of the projects.

And while Neighborhood Youth Achievers is still a shoestring operation, relying on the generosity of a small pool of donors, its orbit is expanding. “We now have connections from kindergarten through high school,” Martin told me. Wainwright’s sister Margo Harris, a veteran educator, has taken the reins and created a charter school, the Grace Hopper STEM Academy, with separate campuses for girls and boys. “Every child we can reach now is one less lost to the streets,” she said.

That sentiment is at the heart of their mission. Wainwright saw kids not as grades or test scores, but as individuals, worthy of opportunity. He valued the skills that hard times can build: the resilience it takes to navigate chaos, the forbearance to forgive parents who fail you, the hunger to prove you are better than your circumstances.

It still amazes me that the passion of one idealistic man — with no resources or professional experience — could drive such an ambitious vision, and find helpers at every turn. He saw a need, and stepped up to meet it. And that not only changed the trajectory of countless children, but helped change the climate of an entire community.

And he never rested on his laurels. There was always more to be done. He wasn’t afraid to ask for the sky, and he never failed to express gratitude.

Wainwright was never one for platitudes. But when I think about how I might honor his life, a quote from tennis star and humanitarian Arthur Ashe comes to mind: Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can.

There is much still left to be achieved, in every neighborhood across the city. And we all have the capacity to open new doors and uplift somebody.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.