Marion Joseph, who changed the way California children learned to read, dies

Her critics liked to point out that she had no formal background in education. Her supporters say she changed the face of literacy education in California and beyond.

The presence of Marion Joseph, once nicknamed the “the Paul Revere of the Reading Wars,” could be likened to a gale-force-strength wind in California education circles as she sought to address and change the state’s approach to teaching children how to read.

In 1982, Joseph left a career serving as a top advisor to state Supt. of Public Instruction Wilson Riles, who in 1970 became the first Black official elected to a statewide position. But it was the work she accomplished during retirement that changed the way education leaders approached reading literacy.

Joseph never really rested, her family and friends say. They don’t even like to use the word retirement.

“We just can’t use that term for her,” her son, Daniel Joseph, said. “She literally never stopped working. She never stopped driving people crazy until they did the right thing.”

Joseph, 95, died Thursday, her family said. During her last days, she urged her friends and family members to continue the mission she championed well into her 80s — ending education inequity by ensuring strong reading skills for all.

“If children could still not read because the education system was not serving them appropriately. … Something was not right and should be fixed,” said Rachel Joseph, her granddaughter. “She was telling people, all of us, that we had work to do and that this fight needed to be continued.”

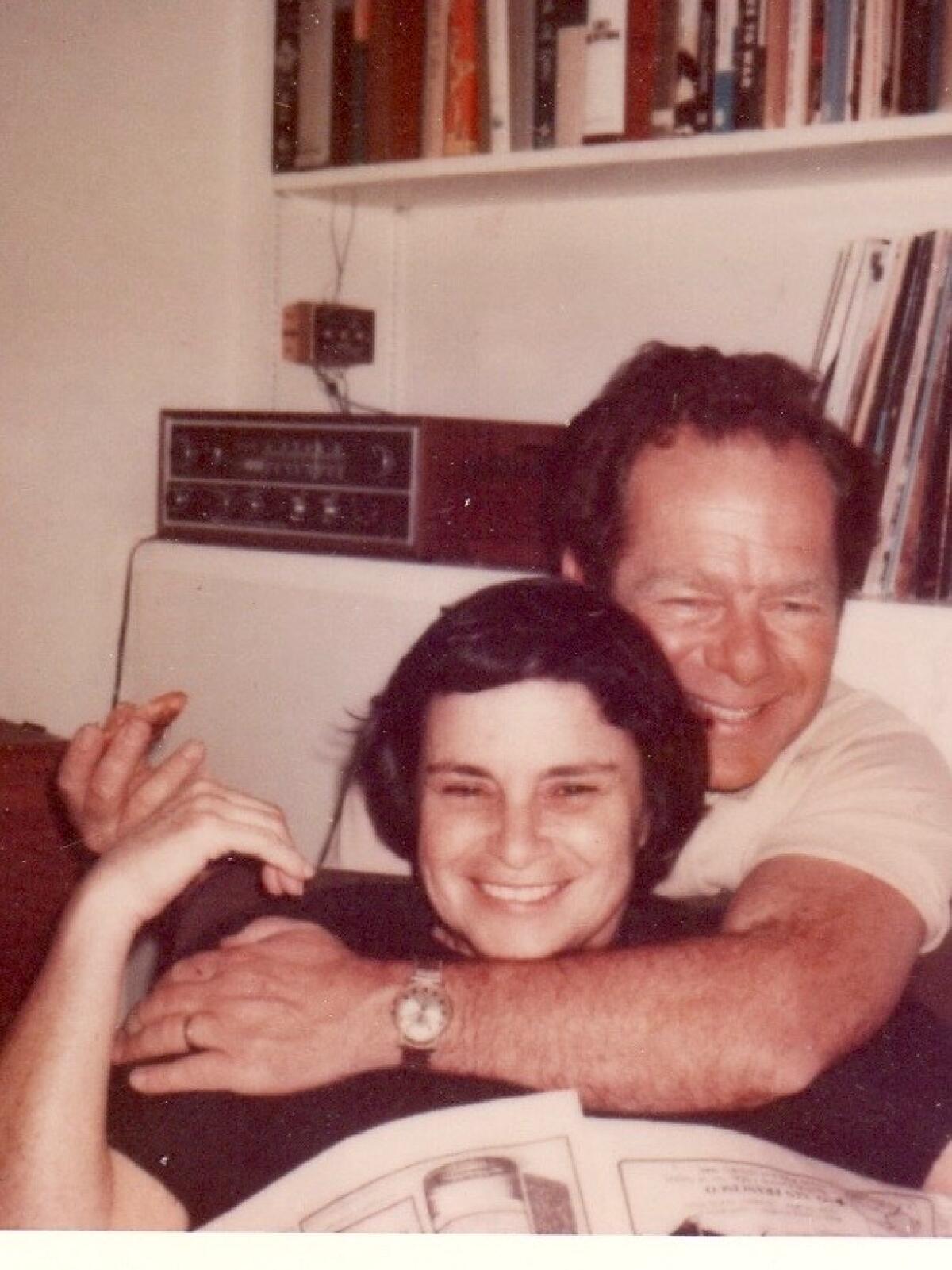

Joseph’s reading crusade began after serving for 12 years as a top advisor to Riles. She retired from her paid job at 56, spending time gardening with her husband, David, and giving tours of her home‘s rose garden. But after her grandson, Isaac, was having trouble reading, she became a deeply involved in researching how reading was being taught.

At the time, schools were applying a literacy theory called whole language approach, which uses literature as a teaching tool and emphasizes learning through the context of words instead of breaking them down phonetically. But Joseph began compiling research that showed children learned better through phonics and sounding out the words, known as phonics-based reading.

“She was in contact with everybody in the country who had something to say about this,” said Bill Honig, who served as state superintendent of public instruction from 1983 to 1993. “She was a force of nature. She had tremendous energy, amazing commitment and she was not going to let go of this issue.”

Joseph continued to advocate for a phonics-based approach, drawing on her 12 years of working in the Department of Education to talk to policymakers.

In the 1990s, standardized test scores showed more than half of fourth-graders in California could not read well enough to understand basic text, prompting urgency. By 1994, she was appointed to a state task force charged with improving beginning-reading instruction for the state’s students. The group settled on an approach that included whole language and phonics, a victory for Joseph.

The state Legislature later passed a bill that mandated the use of phonics in reading instruction.

“She took it as her mission because she was offended by what was happening to California children,” said Janet Nicholas, who first met Joseph when they served on the state Board of Education.

Both Nicholas and Joseph were appointed to the board by then-Gov. Pete Wilson at a time when the state was moving toward creating educational standards and new curricular frameworks. Nicholas said the workload was fast-paced, but Joseph took it on, traveling around the state to meet with educators as the board sought to shape classroom instruction and testing.

Inspired by Joseph’s work in her early 70s, Nicholas said she once spoke at a luncheon to encourage retired educators to get involved.

Joseph’s advocacy, friends and former colleagues say, shaped how reading is taught today, in the state and across the nation.

“She firmly believed that she could, in collaboration with all of the people who became friends and implementers of this work, that she could make a difference,” Rachel Joseph, her granddaughter, said.

Marion Joseph was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., on Oct. 14, 1926. Her family moved to California when she was about 6, and they later adopted two young girls, Lilly and Ella, who had survived concentration camps in Auschwitz.

Her parents’ passion for social justice greatly influenced her own mission for education equity during a time when Black Americans and farmworkers were fighting for civil rights. When Joseph and her husband, David, moved to Sacramento, they housed people participating in Cesar Chavez’s march for farmworker rights.

Rachel Joseph said her grandmother would often say, “It’s simply not right that every child doesn’t have the chance to read and achieve their highest potential.”

Marion Joseph is survived by her sister, Ella Brandt, son Daniel Joseph, daughter Nancy Kinsel and grandchildren Isaac and Rachel Joseph and Jill Kinsel.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.