Getty, Bradbury, Marmont, Lummis: The people behind the famous L.A. buildings

- Share via

Happy Lummis Day, L.A.!

What? You haven’t planned your party yet?

Never mind; the city has. Over two decades, L.A., with the help of a foundation and sponsors, has celebrated the life and work of a man who remains a standout figure in a city overrun by them.

Charles Lummis was a passionate convert to the life and culture of Southern California and one of its most fabulous founding characters.

“I am Lummis! I’m the West!” he exulted.

In 1884, he perambulated more than 3,000 miles from Ohio to L.A., writing newspaper dispatches along the way and becoming a sympathetic ethnographer of Native American culture. Here, he went about town in a corduroy suit with a woven red Navajo sash, an outfit he wore constantly, yea, even unto the White House to visit his Harvard classmate Theodore Roosevelt. He crusaded to restore the state’s tumbledown missions and built the city’s first museum, the Southwest, where he housed his matchless collection of artifacts. He paired off with three wives and many lovers, wrote books, poems and columns and edited and wrote a magazine, “Out West.” As city librarian, he insisted that all Angelenos be allowed to use its collection and discouraged book theft by using a branding iron to burn “LA PUB LIBRARY” into books’ edges.

So of course you want to visit the Lummis House in Highland Park, which he built of boulders dragged up from the Arroyo Seco, the sometimes-waterway of which Teddy Roosevelt told Angelenos: “This arroyo would make one of the greatest parks in the world.” Naturally, we turned it into the Pasadena Freeway.

Surely you’ve seen some name or another blazoned on a public landmark building and wondered to yourself, who are those guys?

Here are origin stories of some (but by no means all) of the buildings — whose names are occasionally women’s names too.

For Subscribers

Who are the people behind the L.A. places you know and love?

Bradbury Building, downtown

The man who envisioned and paid for it was the silver-mine and real estate tycoon Lewis L. Bradbury, whose name adorns a town in the San Gabriel Valley. A dazzled critic called the building “a fairy tale of mathematics.” The interior is what I’d call “Victorian futurist”: glazed brick and tracery wrought-iron staircases and balustrades. Scenes from “Blade Runner” were filmed here.

One of my favorite L.A. tales — that the Bradbury was built on the advice of the architect’s dead brother, sent via Ouija board — has been debunked. The tale went like this: George Wyman, an associate in the office of architect Sumner Hunt, was given the building job after Bradbury didn’t like Hunt’s design. Wyman was reluctant to take the job out from under his boss, but he and his wife were messing around with a Ouija board and got a message from Wyman’s dead 8-year-old brother, Mark: “Take the Bradbury assignment. It will make you successful.” Then about 20 years ago, along comes architect and historian John Crandell, who plumbed contemporary accounts to show that the Wyman fable was not true. Bummer.

Bradbury’s wife, Simoneta, finished the building after he died. The Times called her “the vivacious daughter of a leading Spanish family in Mazatlan,” but Bradbury family papers at UC Davis say she was called the “Cinderella of Rosario,” because she was a maid on Bradbury’s Mexican estate when he met and wooed her.

Oviatt Building, downtown

James Oviatt was thinking of Mission-style architecture for his top-end haberdashery, but a trip to the 1925 Paris Art Deco Exposition changed his mind, and soon, 30 tons of custom glass and adornments — windows, mailboxes, light panels — were on their way to Los Angeles. Movie stars and moguls shopped by the light of the Oviatt’s Lalique lamps.

The Art Deco jewel-box penthouse is where Oviatt lived with his wife, Mary. She was a saleswoman when Oviatt saw her, called her up to the penthouse and proposed. The roof once had a swimming “basin” and sand imported from the south of France for beachy sunbathing.

A ground-floor restaurant, Cicada, is where the flying-escargot dinner scene from “Pretty Woman” was filmed.

For the record:

10:04 a.m. April 25, 2022An earlier version of this article mistakenly said the Cicada restaurant at the Oviatt Building was closed. The restaurant and lounge are open.

Getty Center and Getty Villa, Sepulveda Pass and Malibu

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Two Los Angeles-area museums bear the name of the oilman J. Paul Getty. In 1957, Fortune assessed him to be the richest American, and his worth in the 1970s, back when billionaires weren’t a dime a dozen, was something between $2 billion and $4 billion. In 1971, the Times writer and astute cultural critic (and my old friend) Bevis Hillier spent a weekend with Getty as a houseguest of the Duke of Bedford and concluded that Getty was “one of the most boring people I have ever met” and a man devoted equally to pinching pennies and women’s bottoms.

Getty’s charitable trust of more than $7 billion makes it probably the deepest pockets in any art sale. After an aristocratic cousin of Queen Elizabeth II’s sold off a Titian, “The Death of Actaeon,” the Getty acquired it. But Britain, its amour propre stung at losing such a treasure, halted its export and raised money to keep it in the country. Once in a while, the flow of antiquities has gone the other way: The Getty has had to return dozens to their countries of origin over questions about how they were acquired.

The Getty, like Julius Caesar’s Gaul, is divided into three parts.

The Getty Center hovers at a hilltop over the 405 Freeway like a lenticular cloud. Its collection runs to paintings, furniture, statuary, manuscripts, sundry objets de vertu and an authoritative collection of photography.

The Getty Villa in Malibu is modeled on a villa buried by the volcanic lava flows that destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum 200 centuries ago. It was originally built after Getty’s place nearby ran out of room to keep all his stuff — and who among us can’t identify with that? Getty never visited it, but he is buried there.

The Getty Conservation Institute, with facilities at both museums, is the Oz-behind-the-curtain scientific undertaking that helps the world preserve its art treasures.

The wrath of the webbing clothes moth. During the yearlong COVID-19 closure, the Getty devoted more than 6,000 hours to eradicating this one insect.

Skirball Cultural Center, Sepulveda Pass

Like the Getty, it sits atop a hill above the Sepulveda Pass and has its own exit sign on the 405. It’s a meeting and exhibit space describing itself as “guided by the Jewish tradition of welcoming the stranger and inspired by the American democratic ideals of freedom and equality.”

Jack H. Skirball may have been the world’s only rabbi/developer/philanthropist. He spent nine years as a rabbi but moonlighted as a film salesman and wound up producing nearly 60, most of them short subjects but two of them Hitchcocks.

Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena

Even if you haven’t visited this museum, you’ve seen it. It stands near the “starting line” of the New Year’s Day Tournament of Roses Parade.

Founded as Pasadena’s art museum, it was facing ruin in 1974 when it agreed to Norton Simon taking it over, paying its bills and installing his own enormous and top-notch collection there.

Simon’s wife, the Oscar-winning actress Jennifer Jones, oversaw the museum’s renovation after Simon died. A Times critic called him “the mercurial Medici of Los Angeles art.” He was a sharp-elbowed businessman who leveraged railroads and canned tomatoes and other enterprises into a fortune. And he spent a lot of it on Old Masters, Impressionists, Asian treasures — 12,000 works in all.

“You see creativity [in art],” Simon once said. “You see that this man spent his life painting. You wonder what that expression meant to him, and you wonder what your expression means to you. What kind of nut spends his whole life painting? What kind of nut am I? What is my life expressing?”

The L.A. area has long been home to ostentatious houses. Pasadena had Millionaire’s Row over 100 years ago. These days Bel-Air has “The One” and the “Starship Enterprise.”

Hammer Museum at UCLA, Westwood

Armand Hammer is one of those characters whose career, both self-mythologizing and real, can scarcely be bound by a book: a wheeler-dealer who parlayed knowing Lenin into a nine-year career living in the fledgling Soviet Union as a manufacturer and import-export businessman. He was a medical doctor who never practiced but clung to the title.

Some years ago, in New Mexico to write about the dedication of a boarding school Hammer funded, I put a question to the actor Cary Grant, a visiting VIP, about “Mr. Hammer.” “Ah, ah, ah,” Grant corrected me with a finger wag. “It’s Dr. Hammer.”

The school was a favorite project of Prince Charles, and funding it got Hammer into the royal good graces. Charles reportedly wanted to make Hammer a godfather to his elder son, Prince William. His wife, Diana, put a stop to that.

Hammer, like Simon, had flirted with giving his art collection to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art but opted instead for a building that bore his name. Hammer had reportedly demanded that other donors’ names be taken off the LACMA galleries where his paintings would be hung and that lifesize portraits of him and his wife be displayed permanently at the museum. As they say in the telling of tales, you haven’t heard the half of it.

The Broad, downtown

Eli Broad, who died a year ago, made his billions in insurance and in the home-building business. Broad was a pioneering big-donor philanthropist with a foundation promoting science, education and civic engagement. He was also a deep-pocketed patron of modern art, helping to raise the profiles of dozens of 20th century artists.

The Broad Museum has almost 2,000 pieces from the collection he built with his wife, Edythe. Broad had a hand in creating downtown’s Museum of Contemporary Art and had worked with LACMA, but he too chose a museum of his own.

The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, San Marino

It’s a legendary name from California history, but it was not the uncle, the Gold Rush tycoon Collis P. Huntington, who founded the place, but his nephew Henry, who made his fortune in L.A. real estate and married his uncle’s 63-year-old widow, Arabella.

Huntington, said California historian Kevin Starr, was a “heroic spender.” The couple hoovered up manuscripts, paintings, sculpture and et ceteras for their estate, now set among more than 130 acres of varied and inventive gardens. Today, the collections run to 11 million items across 1,000 years of human history.

Star turns: the famous 18th century British portraits “Blue Boy” and “Pinkie.” I once took English visitors here, and they stopped dead in front of the portraits and demanded, “What are those doing here?”

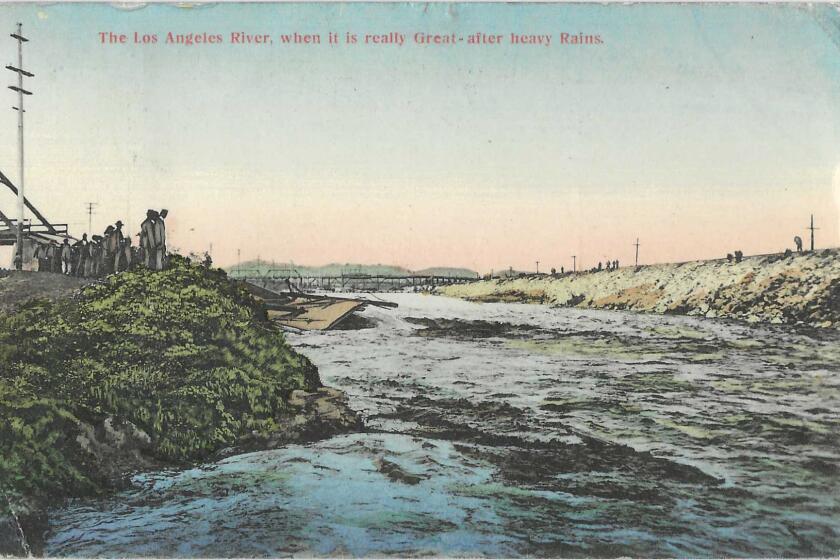

After one too many floods, L.A. turned its river into a concrete channel. Today and in the future, the river could be part of the answer to some of the city’s problems.

Now that we’ve toured the billionaires’ buildings, let’s move on.

Chateau Marmont, Hollywood Hills West

The lounge-around hangout of the beautiful people, and anyone else who can afford the price of a room, or at least a cocktail, is named for the street it sits on, Marmont Lane. But where did “Marmont” come from? Most likely from a virtually forgotten silent-film leading man, the English-born Percy Marmont. In dozens of films and on the stage, he played the stoically romantic hero whose characters were usually Lord or Sir or Colonel something. His IMDb biography suggests that “his perpetually serious, somewhat tortured demeanor may well have been compounded by a hernia he suffered while picking up Clara Bow in ‘Mantrap.’ ”

Margaret Herrick Library, Beverly Hills

The Herrick is one of the region’s many specialty libraries, and it just reopened. It’s a natural for L.A., a research resource entirely about movies, with many thousands of papers: production notes and screenplays, clippings, promotional materials, photographs, musical scores.

Don’t think that you can check out, say, Thornton Wilder’s screenplay for “Strangers on a Train” — all the material is for use only on-site. The collection was begun in 1928 and was later named for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science’s librarian and executive director, Margaret Herrick. It is Herrick who in all likelihood gave the saucy name “Oscar” to the academy’s award of merit; it was, she wrote in a 1959 letter to a Merriam-Webster dictionary editor, a “thoughtless quip” that she “regretted more times than I care to remember.”

Simon Wiesenthal Center, Pico-Robertson

With its companion Museum of Tolerance, the institution supports Holocaust research and campaigns for human rights for Jews the world over. It’s named for the legendary Holocaust survivor and investigator whose work brought some thousand Nazi war criminals to justice. (The nation’s oldest Holocaust museum, the 61-year-old Holocaust Museum L.A., stands a few miles away in Pan Pacific Park.)

Simon Wiesenthal came here in 1977 for a dedicatory ceremony. He also took in a concert at which a teenage Jewish pianist named Yefim Bronfman played Rachmaninoff’s “Piano Concerto No. 3.” As wonderful as it was, Wiesenthal told conductor Zubin Mehta backstage, he could not help thinking of “the others, the ones we lost in the Holocaust, how many brilliant young musicians, poets, painters …”

A.C. Bilbrew Library, Willowbrook

The south L.A. civic leader Madame A.C. Bilbrew was said to be the first African American to have her own radio show. Her name appears with some frequency in The Times’ stories from the 1920s to the 1950s, like one in 1957 noting her “new show” on radio station KPOP. Her singing group performed for white women’s clubs, and after it appeared in the 1929 Black-cast movie “Hearts in Dixie” (in which Bilbrew played a “voodoo” or “hoodoo” woman), it put on a special show at the Orpheum Theatre. In 1932, she sponsored what The Times called the “first real Negro drama” staged in L.A., a production of the play “Hoo-Dooed,” performed at the Philharmonic Auditorium, the first permanent home of the L.A. Philharmonic.

Alma Reaves Woods-Watts Branch Library, Watts

In the 1990s, the city of L.A. dropped, like the very hot potato it was, a policy that new libraries would be named for those who gave more than $1 million to build them. The city backed down after the Watts community insisted that its new branch library be named for Alma Reaves Woods, the woman locals knew as “the lady who built the library.”

Woods worked for decades to build a library in Watts, buying cheap books and handing them out to kids, lugging books from a faraway library to a housing project where she herself had once lived and campaigning door to door for a bond issue to build the branch library that now bears her name.

With flexibility and perseverance, your chances of staying in the historic beach bungalows are better than you think.

Masao W. Satow Library, Gardena

L.A. County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn presided over the library’s dedication in 1977, calling Masao W. Satow “one of America’s most distinguished civic leaders.” The child of Japanese immigrants, Satow graduated in 1929 from UCLA’s old campus on Vermont Avenue and later went to work for the YMCA as a community leader.

In the weeks after Pearl Harbor, he addressed a Lawyers Club audience on the topic “We too are Americans.” In February 1942 — before he and his wife were sent off to a relocation camp in Colorado — he presented to county supervisors a parchment with the signatures of hundreds of Japanese Americans pledging “absolute allegiance” to the U.S. He organized YMCA groups in his detention camp and in 1946 came back to California to head the Japanese American Citizens League and, later, to serve on the state’s advisory committee on civil rights.

Ávila Adobe, Olvera Street

At 204 years old, it’s the oldest house left standing in the city of L.A. — imagine the built-up equity! Its builder and first resident was the rich pioneer rancher Francisco José Ávila, the city’s mayor in 1810. For nine days in January 1847, Commodore Robert Stockton took over the building as his headquarters in the Mexican-American War, joined by the fabled scout Kit Carson. The Ávila family moved out in 1869, and the place slipped into desultory habitation. It was almost lost twice: when the city condemned it in the 1920s, and the “mother” of the re-created Olvera Street, Christine Sterling, undertook to save it; and again in the 1971 Sylmar earthquake. The adobe was restored as an example of L.A. life in the 1840s.

It isn’t L.A. County’s oldest residence, though. The Gage Mansion, built in 1795 by the Lugo family and named for a California governor who later lived there, is now owned and encircled by a mobile home park in Bell Gardens.

Moviemakers, painters and authors have long opined on the quality of L.A.’s light. A Caltech scientist illuminates on why our light is so remarkable.

Gamble House, Pasadena

This is the flagship of Craftsman houses, built in 1909 by the Greene and Green architectural firm for the Gamble family, of the Procter & Gamble fortune. It cost $55,000, twice as much as the midsize school going up in Pasadena at the time.

The supersize California bungalow fit into the contours of land and was designed with art glass and natural wood throughout. The Gamble family heirs gave it to Pasadena in 1966; 11 years later, it was declared a national historic landmark. I have never heard the breath of suggestion to tear it down, but this is one of the rare buildings that people — me among them — would lie down in front of bulldozers to save.

Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, Hollywood

Showman Sid Grauman’s over-the-top theater opened in May 1927 with the premiere of Cecil B. DeMille’s epic “The King of Kings.” Its equally famous forecourt is paved with cement squares into which stars have embedded handprints, footprints and signatures.

Legend says that practice began when film star Norma Talmadge, invited by Grauman to inspect the work in progress, stepped into wet cement, and Grauman realized he had a double attraction. (The Times story says that in January 1926, Talmadge was handed a shovel by actress Anna May Wong — a metaphorical Hollywood groundbreaker herself — to turn the first dirt in the construction project.) The Talmadge origin story is now as firmly fixed in the anthology of Hollywood as the cement itself. She may have re-enacted the moment for an audience, because a photo shows her creating her square surrounded by a crowd, and the date daubed alongside her name is May 18, 1927 — the day of the DeMille premiere.

The theater was sold in 1973 to the Mann chain, which tried without great success to get Angelenos to start calling it “Mann’s Chinese Theatre.” Ditto the Chinese company that bought naming rights in 2013 and rechristened it “TCL Chinese Theatre.” That naming contract expires next year. Who next is going to spend many, many dollars to try to rewrite history that’s set in cement?

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.