L.A. County to settle for $1.85 million with whistleblower who alleged child welfare failures

Los Angeles County supervisors on Tuesday approved a $1.85-million payment to settle a whistleblower lawsuit brought by a former county social worker who alleged he had uncovered a pattern of systemic misconduct that endangered thousands of children, records show.

According to an amended civil complaint filed in L.A. County Superior Court on June 23, 2020, Dennis Finn was a social worker with the county’s Department of Children and Family Services for 24 years when he was fired on May 22, 2019, after repeatedly raising his concerns with the department and becoming a whistleblower for California state officials.

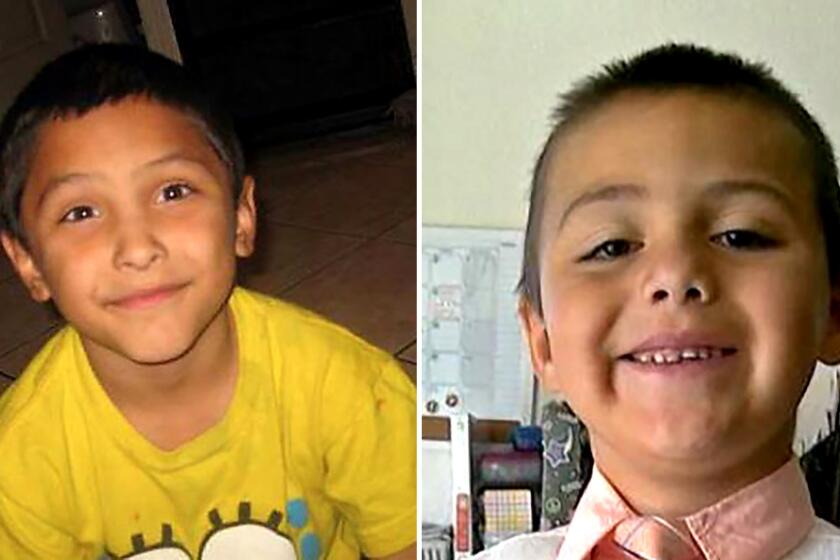

Finn’s suspicions of misconduct arose following the death of Gabriel Fernandez, the complaint stated. The 8-year-old boy died on May 24, 2013, two days after he was beaten in his Palmdale home.

A Times review of confidential documents in the days after his death revealed that county social workers left Gabriel in the care of his mother and his mother’s boyfriend despite six investigations into abuse allegations involving the mother over the previous decade.

Gabriel’s mother, Pearl Sinthia Fernandez, was sentenced to life without parole in 2018. Her boyfriend, Isauro Aguirre, received a death sentence.

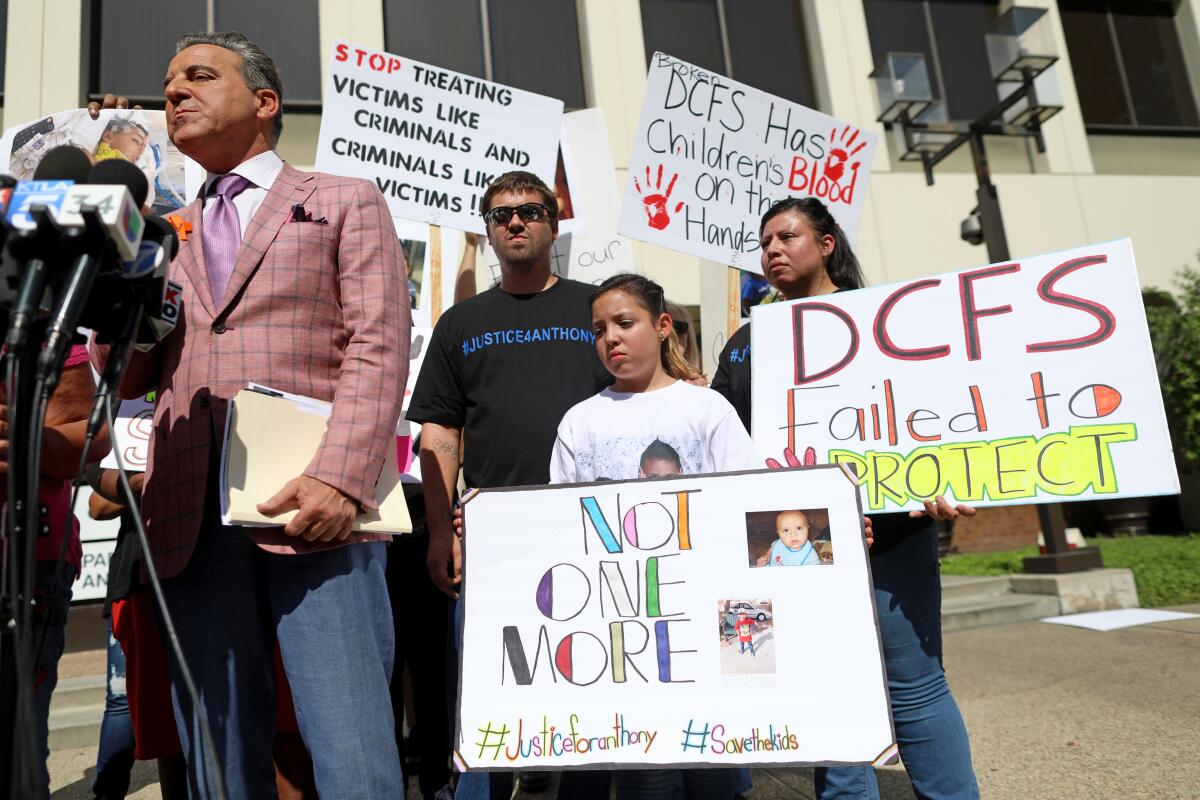

The case put DCFS under intense scrutiny. Officials assembled a Blue Ribbon Commission on Child Protection, which recommended a series of reforms.

Finn, meanwhile, started digging.

Barbara Dixon provided in-home counseling to both boys, whose deaths spotlighted egregious lapses in L.A. County’s child welfare system.

By 2016, he’d noted ongoing issues similar to the delayed or inappropriate responses leading up to Gabriel’s death, the complaint stated.

Finn discovered that calls reporting suspected child abuse, neglect and exploitation, which should have warranted immediate action by authorities, “were being systematically delayed,” according to the complaint.

Some calls were not entered until later dates, the documents stated, and others were put into DCFS systems under an improper code, as consultations instead of emergency response referrals.

“These instances of delays and miscoding resulted in deep systematic flaw[s] whereby children suffered continued abuse, severe injuries, and other brutal acts due to a failure of defendants to ensure that their reporting and intervention were being conducted properly and in a manner compliant with relevant regulations,” the complaint stated.

Finn reported the problems internally but later took his concerns to union representatives, hotline supervisors, the California Department of Social Services and other county agencies after his initial efforts were ignored or retaliated against, court documents stated.

A county spokesperson did not offer a statement regarding the case or the settlement.

Finn’s lawsuit alleged the retaliation “initially took on three main forms.”

The department undermined Finn’s long-term disability accommodations that had previously allowed him to work from home, court documents stated. He was returned to work in December 2016, after he filed a complaint with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and mediation.

In early 2017, Finn was reassigned “where he faced even more hurdles and retaliatory action,” the complaint stated.

The department’s senior management accused him in February of that year of falsifying medical records he’d submitted in support of workers’ compensation and disability claims, according to the complaint. The investigation remained pending for weeks until he was cleared and told the allegations couldn’t be substantiated on April 10, 2017, the complaint stated.

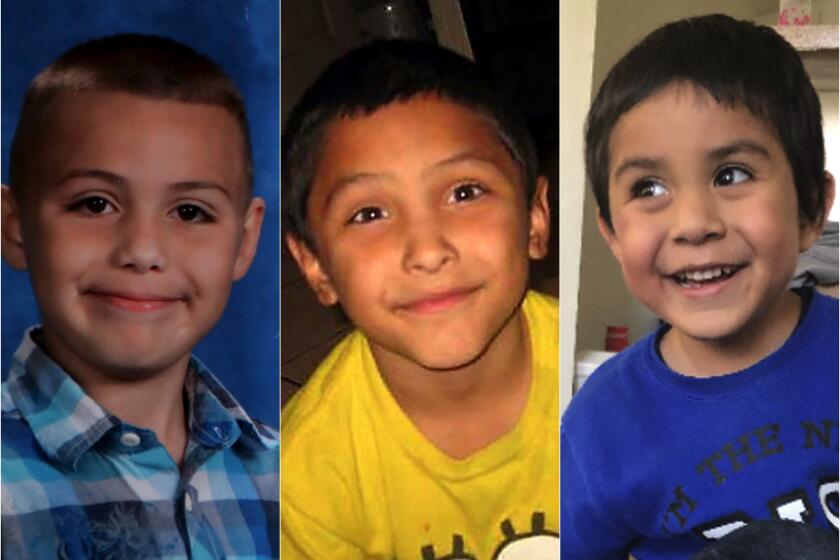

Anthony, Noah, Gabriel and beyond: How to fix L.A. County DCFS

“Just a few months later in August of 2017, he was summarily downgraded on his annual evaluations,” the complaint stated. “In previous years, [Finn] was held in high regards as a great employee and advocate of DCFS.”

He had been tasked at various points with training new hires at the department, and from 2013 to 2015 his performance reviews rated him as “very good,” the complaint stated.

“Additionally, Plaintiff Finn had garnered numerous awards, commendations, distinctions, and positive evaluations throughout his decades with DCFS,” the complaint stated. “The downgrade of Plaintiff Finn’s annual performance suddenly in 2017, after he began reporting flaws in the DCFS system and retaliation, is a hallmark of systematic retaliatory actions taken against Plaintiff Finn by DCFS.”

By June 2017, he had become a confidential whistleblower with the state’s Department of Social Services and a state investigation was launched, the complaint said.

State investigators found, by that December, several entries in the county’s system that weren’t in compliance with “state regulations relating to proper date on referrals,” the complaint stated.

In late October 2017, state investigators asked Finn for current examples of misconduct or bad practices, court documents said. He browsed through the county’s reporting systems and “quickly found an entry of child fatality and several other dangerous entries.”

“The most notable was the Jaliyah Hickman and Camille Brewster case ... which had occurred just a few weeks prior,” the complaint stated.

In that case, two sisters, ages 1 month and 7 years, were killed by their mother, Jasmine Hickman, “who was in the midst of reported bizarre behavior, psychotic and unstable behavior,” according to the complaint.

The case of 10-year-old Anthony Avalos exposes serious failures by the Los Angeles County child protection system to intervene before his death.

Finn found that several people, including the girls’ grandmother and Hickman’s landlord, who was required by law to report suspected child abuse, called a county hotline to share concerns that Hickman was behaving erratically and posed a danger to her children; there were at least three calls to the hotline, “none of which were properly evaluated, recorded, or acted upon,” the complaint stated.

In one instance, a social worker wanted to recommend more immediate intervention, but a supervisor overruled the employee and downgraded the response “despite two prior calls, a 911 call and a supposed police visit,” the complaint stated.

Early on the morning of Oct. 19, 2017, Hickman was seen walking on public streets, carrying and breastfeeding her newborn daughter and holding her 7-year-old daughter’s hand, according to the documents. The three were naked and covered in a white powder. As they walked, Hickman tried to open the doors of parked cars.

The sudden resignation of Bobby Cagle caps a tumultuous period for the nation’s largest child protection agency and will force L.A. County leaders to grapple with major policy questions.

“Ultimately, all three were found unconscious, laying on the ground, in a parking lot several blocks from Jasmine’s home,” the documents stated. “The newborn daughter died that day. Shortly thereafter, the 7-year old daughter died.”

Hickman was arrested and charged with two counts each of murder and child abuse, court records show. Her criminal case is ongoing.

Although state investigators told Finn he would be protected by whistleblower laws when they asked him to access county records, retaliation by county officials continued, according to the complaint.

Around May 18, 2018, he was accused by DCFS of improperly accessing a referral in the Hickman case and of changing the original date and time of the referral, the complaint stated. He was fired on May 22, 2019.

In his discharge papers, department officials faulted Finn for accessing records about a high-profile case and made “highly specific allegations” about which records he accessed and the record he supposedly fabricated, the complaint stated.

But the county’s claims ignored that Finn was acting under the direction of state investigators, “and was doing so rightfully and in the name of child safety,” the complaint stated.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.