After 20 years in prison, man found innocent of a murder

Alexander Torres was convicted of murder on shaky evidence.

A witness to the shooting on New Year’s Eve in 2000 told police at first that the assailant hadn’t seemed to know his victim, while Torres had a long history with the man. The witness changed his story more than once and named Torres as the shooter only after several rounds of interviews.

Another witness initially identified Torres as the killer, but admitted later that he had picked him from a photo lineup simply because he bore the closest resemblance to the shooter.

And Torres had a solid alibi: He had been celebrating the new year at his mother’s house in another part of Paramount when Martin “Casper” Guitron was gunned down. A cast on his hand made it unlikely he would have been able even to pull the trigger.

Torres was sentenced to 40 years to life in prison. But after spending more than 20 years behind bars, the now-42-year-old has been cleared of the killing and released from prison.

In April, after a review of the case, a judge found Torres factually innocent, concluding that a series of missteps had led to his arrest and wrongful conviction.

For the record:

9:19 p.m. June 1, 2022An earlier version of this article said a judge found Alexander Torres factually innocent last month. It was in April.

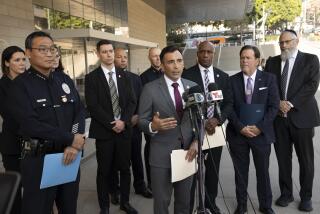

The judge’s order followed a review of the case by the California Innocence Project and the office of Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón, who campaigned on a promise to take a harder look at questionable convictions. Torres’ sentence was vacated in October with little fanfare, but his release was announced at a news conference Wednesday arranged by Gascón’s office.

In a statement, the district attorney apologized to Torres and praised the work of his revamped Conviction Integrity Unit. “While it is this office’s job to hold people accountable for the harm they cause, it is equally important that we critically reexamine past convictions,” the statement read.

The exoneration could provide a boost for the embattled district attorney, who is under heavy criticism from inside and outside his office over his policies aimed at reducing mass incarceration.

Though his predecessor, Jackie Lacey, often touted the work of her office’s case review unit, she limited the types of cases the unit could review, leaving it relatively hamstrung compared with similar units in other large cities such as Chicago, Houston and New York.

When he took office, Gascón appointed to his transition team a number of civil rights attorneys and lawyers with expertise in reviewing the integrity of past convictions. He also pledged to alter the way the office reviewed such cases.

Mike Semanchik, a managing attorney with the California Innocence Project, said that while more could still be done, the unit under Gascón has “certainly invested a lot more time, effort and resources into investigating these sorts of cases than prior administrations have.”

The California Innocence Project is reviewing about a dozen other convictions with the district attorney’s office, Semanchik said.

Audrey McGinn, an attorney who worked on Torres’ exoneration for the California Innocence Project, said that it is unclear what or who was to blame for the wrongful conviction, but that often investigators pay more attention to evidence that supports what they already believe.

“I think it’s a product of tunnel vision and ignoring the red flags, especially when you put a photo in front of a witness and say, ‘This is the guy,’” she said. “He was an easy target, and it was easy to establish motive.”

Guitron was walking with a friend near Somerset Boulevard and El Camino Avenue in Paramount, a city of roughly 55,000 residents east of Compton, when a blue 1990s Chevrolet Caprice stopped in the middle of the road. A man got out and walked up to Guitron, repeatedly asking, “Are you Casper? Are you Casper?” using Guitron’s street name, before shooting him.

In a joint motion for factual innocence, attorneys for both sides agreed that Torres would have recognized Guitron, with whom he’d had a long-simmering feud stemming from their membership in rival gangs. The motion also cited the accounts of several family members who reported that at the time of the shooting Torres was celebrating New Year’s and his mother’s birthday at her house in another part of town. Furthermore, no murder weapon was recovered and no other physical evidence connected Torres to the scene, according to the filing.

The effort to exonerate Torres got a significant break when his family hired a private investigator, who managed to track down the driver of the Caprice. The driver eventually led authorities to the man they now believe was the shooter. That man, like the driver, has since been arrested in the Paramount slaying and has been incarcerated since the early 2000s after his conviction for a series of armed robberies.

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 161 people were exonerated of murders and other serious crimes in the country last year — adding to the hundreds of those freed since the late 1980s. In all, they spent a combined 1,849 years behind bars. Nearly half had been charged with a murder they didn’t commit. Black people accounted for a disproportionate number of the wrongfully convicted.

In a majority of the cases from last year, the wrongful convictions resulted from “official misconduct,” either by prosecutors, police or forensic experts, the organization found, while 47 were due to mistaken identifications by witnesses. An additional 19 exonerations came about because of “proven false confessions,” the organization determined.

UC Davis law professor Irene Oritseweyinmi Joe said that cases like Torres’ should trigger an intensive, top-down review of what went wrong. Police, prosecutors, judges and even public defenders should all face the same scrutiny, given the key roles they play when the justice system doesn’t work.

“Every action that could’ve been taken even if it wasn’t required to be taken at the time [should be] reviewed to make sure that it doesn’t happen again,” Joe said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.