Column: My broken sprinkler sent me on a quest. Can dowsers help us through the drought?

So how did I end up with a city employee traipsing across my front yard with divining rods on a recent evening, searching for underground water?

The answer begins with a boneheaded blunder on my part. I accidentally clipped a sprinkler head on the edge of the driveway while pulling into my yard, and water began bubbling up from underground.

I’d never used those sprinklers and thought the line was dead when I bought the house five years ago. Clearly it was not, and water was now running down the street in the middle of a drought. So I called the emergency number for the Pasadena Water Department, and the operator promised to send a troubleshooter.

A friendly chap showed up in minutes and did a quick assessment. There was no way to stop the gusher without turning off the main water supply to the house, he said. So he took care of that and said I’d have to call a plumber to figure out where the underground sprinkler pipe tied into the main water line, then have him dig down and fix the rupture.

But how would a plumber locate a pipe buried under dirt and asphalt?

California residents in May saved 3.1% more water than the same month in 2020, the baseline year against which current data are measured. But officials say more is needed.

The troubleshooter said he’d be right back. He went to his truck and returned with two L-shaped metal rods, each about two feet long. He walked to and fro, holding the rods parallel to the ground and several inches apart. Every once in a while, the rods crossed. In each spot where they did, he bent down and planted a little blue flag and said that’s where I’d likely find my bad pipe.

“I thought that was voodoo,” I said politely.

He told me he didn’t understand the science behind dowsing, if there’s any at all, but he knew it worked. He said he had a $4,500 gadget in his truck to search for water lines, but he had more faith in the rods.

Well, this piqued my interest, and I began to do a little digging of my own. Is there anything to dowsing, and if so, might a battalion of dowsers help get us through the drought by identifying underground aquifers and streams?

“There are energies involved with the flow of water underground, and that creates an electromagnetic field,” said Sharry Hope, an Oroville resident who told me she’s been dowsing for decades. She said she feels that energy when she uses her rods.

I asked Hope if I could be a dowser myself.

“You should be able to do it, if you know what you’re doing,” she said.

Could I use coat hangers as my rods?

“Sure,” Hope said.

I went into my closet, grabbed a coat hanger, straightened it, cut it in half and formed two L-shaped rods. I went out to my front yard and walked around like the troubleshooter had.

Nothing happened.

I held the rods over the kitchen sink, and then over a bucket of water.

Nothing.

Larry Bird, another Northern California dowser, told me his grandfather had “witching sticks,” and he picked up the craft. He told me water has a current he can detect with his rods.

“I can tell you where water is, how deep it is and how many gallons you’re going to get,” said Bird, who began to lose me when he talked about buried bodies, pyramids and what he called stone skulls.

Next I called Rob Thompson, a wine country dowser who was featured in a New York Times article last year about how water witches, as some of them refer to themselves, have been in high demand because of the drought. Thompson said the craft is hundreds of years old, and that he’s a third-generation dowser who’s been at it for more than 40 years.

“I’ve made a lot of skeptics believers by actual proof,” he said, telling me he’s often hired after people drill multiple times on their property and come up dry.

When they hire him — at $1,500 for the first two hours and $650 per hour thereafter — they’re “blown away” by the result, Thompson said. He said a dowser has to appreciate the “magnetic polarity of the Earth,” clear the mind, and be open to the possibility that a person can tap into an undeveloped sixth sense.

“I have the gift,” Thompson said, telling me he can stand in one spot with his rods and gradually rotate until he has a sense of where water can be found. “Our mind is so much more powerful than we’re led to believe in America. America’s dumbed down, but you let go of all that and you can be so much more.”

I am, by nature, a skeptic about these kinds of things. Twelve years ago, when an animal communicator sent me the transcript of a conversation she said she’d had with the raccoons who were tearing up my yard in Silver Lake, I had trouble wrapping my head around that.

I’m somewhat less skeptical about water dowsing, despite my coat hanger failure, but two underground water experts I spoke to added to my doubts. Each of them said there’s a lot of underground water, even in drought-stricken California. Locating good places to drill can be tricky, but they said that by understanding watershed landscape, geological maps and local well-digging history, it’s possible to make educated guesses.

Timothy K. Parker, a state-certified hydrogeologist, said he’s not a dowser and can’t comment on the theory about electromagnetic currents.

“But these dowsers can be using some of the same information a hydrogeologist would use to identify potential drilling locations,” Parker said.

Matt O’Connor, a certified engineering geologist with a Ph.D. in forest hydrology, chuckled when I told him what I was calling about.

“People can pretty easily know where there’s gonna be water and have enough of a success rate that people will buy into” claims that dowsing works, O’Connor said.

And yet two longtime wine growers and vineyard managers told me they have faith in Thompson. Doug Hill said he’s hired Thompson five or six times over the years and the dowser has been right more than he’s been wrong.

Hill said there were dowsers in his own family, and that he has used the witching sticks himself on occasion. Hill said that when Thompson claimed success for another grape grower, Hill called the vintner for verification and was told that after 17 or 18 drilling efforts came up dry, he turned to Thompson. The dowser told him where to drill, how deep to go and how many gallons per minute he’d be able to pump.

And he nailed it.

“I am a believer in the magic, and in the possibility that humans have abilities we don’t fully understand,” Hill said, telling me that with Thompson’s assistance, he has held the rods himself and felt a strong pull when a water source has been detected.

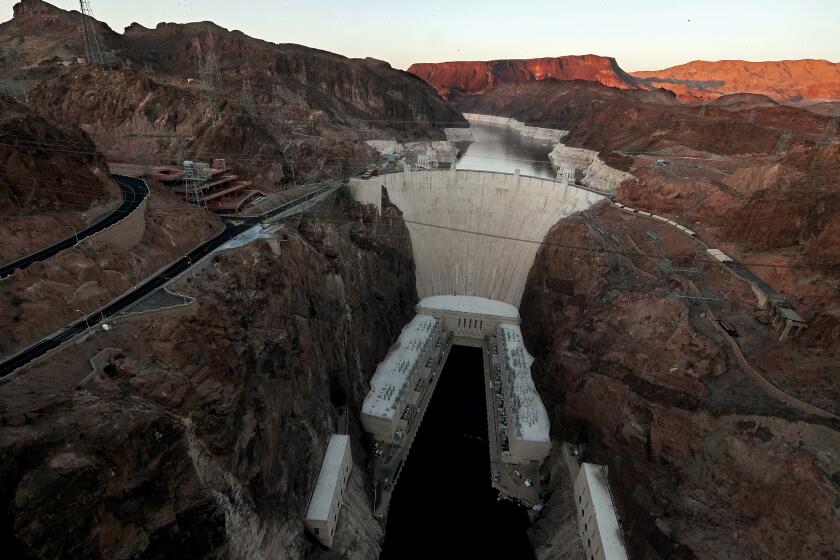

The latest maps and charts on the California drought, including water usage, conservation and reservoir levels.

Glenn Proctor, who grows Zinfandel and petite Sirah in Healdsburg for his Puccioni Vineyards label, told me it can cost $25,000 to drill a well and come up dry. So he likes to hedge his bets by hiring both conventional underground water experts, and Thompson, to see if they agree on the best drilling locations on land Proctor’s family has worked for 100 years.

“For me, if I’ve got agreement from two sources, hopefully it’s less likely that when I drill, I’ll hit a dry hole,” said Proctor, who told me Thompson has been right before on his property. He’s running low on water now, Proctor said, and he’s hired Thompson again to locate a good spot for another well.

By the way, both state-certified water experts I interviewed suggested that water conservation and reclamation are better ways to address the California drought in the long run, and one pointed out that pumping underground water has led to the ground sinking in parts of the San Joaquin Valley.

As for my own water emergency, when I hired a plumber, he and I determined that my corroded underground pipe was not where the dowser had planted the blue flags.

I have not yet received the bill for the repair, which involved digging a large hole in my driveway.

I’m just hoping it’s a lot less than $25,000.

Steve.lopez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.