After string of teen overdoses, L.A. schools will get OD reversal drug naloxone

Los Angeles public schools will stock campuses with the overdose reversal drug naloxone in the aftermath of a student’s death at Bernstein High School, putting the nation’s second-largest school system on the leading edge of a strategy increasingly favored by public health experts.

The move, which will affect some 1,400 elementary, middle and high schools, is part of the district’s newly expanded anti-drug strategy, quickly assembled in response to student overdoses. Officials on Thursday said nine students had overdosed across the district in recent weeks, including seven linked to the Bernstein campus and Hollywood High School. The response plans will also include expanded parent outreach and peer counseling.

The death of 15-year-old Melanie Ramos, who died in a school bathroom last week after ingesting a pill that she bought from another student, has left the campus community reeling and touched off concern among parents throughout the 430,000-student district. The pill contained fentanyl, an opioid that is deadly in small doses.

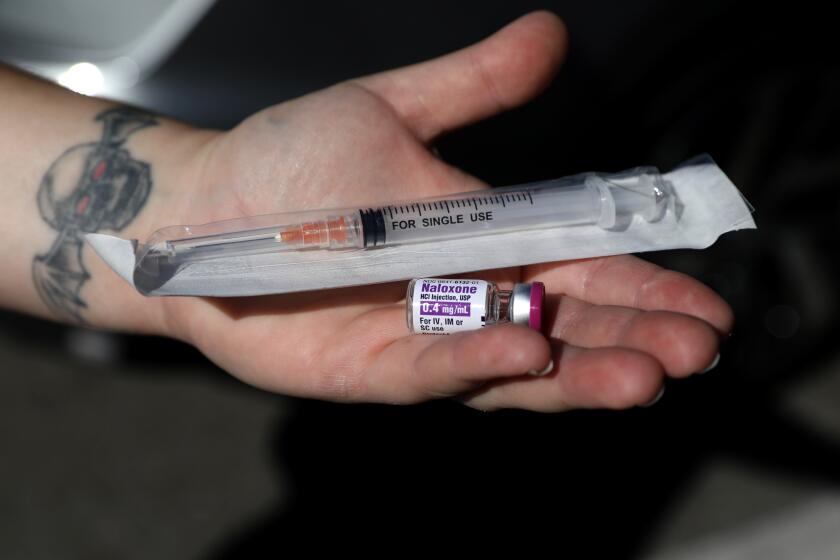

Naloxone is highly effective at reversing opioid overdoses if administered quickly by a nasal spray or injection. L.A. Unified will be using the nasal version, which is as easy to use as any other nasal spray. Naloxone won’t harm someone if that person is overdosing on drugs other than opioids, so it’s always better to use it in the case of a suspected overdose, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The medication “has a limited but highly effective way of reversing that condition, allowing individuals to restore breathing,” said L.A. schools Supt. Alberto Carvalho, adding that this “safe solution” lasts 30 to 90 minutes, providing first responders and medical professionals the opportunity to care for a student.

The state and L.A. County have worked hard to make Naloxone more widely available. One of the hurdles, though, has been the price of the inhalable version, Narcan.

“We have an urgent crisis on our hands,” Carvalho said. “Research shows that the availability of naloxone along with overdose education is effective at decreasing overdoses and death — and will save lives. We will do everything in our power to ensure that not another student in our community is a victim to the growing opioid epidemic.”

The extent of the crisis should not be underestimated, said Dr. Brian Hurley, an addiction psychiatrist and the medical director of the county health department’s division of substance abuse prevention.

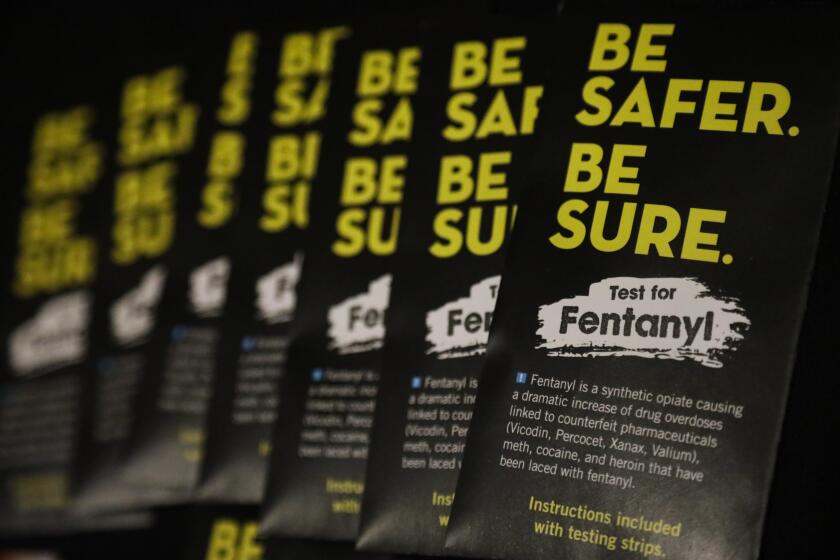

“We are now in the worst overdose epidemic in the United States history and the worst overdose epidemic in Los Angeles County history,” Hurley said. “And a lot of that is attributable to this high potency opioid fentanyl that’s found its way into illicitly manufactured pills and to other drugs of abuse.”

California law permits K-12 schools to provide and administer naloxone, but does not require it. Michigan has adopted similar rules.

Rhode Island requires all schools to have naloxone, and it can be administered by “any trained nurse-teacher” without fear of liability. School employees also can decline to administer the medication. New York state offers four free doses of naloxone to every high school, but they don’t have to accept it. Currently, New York City schools do not have a policy to keep it in stock, a district spokesman said.

Some California colleges and universities are required to have the drug in stock under a bill signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom in August.

At least two other large school districts in the state have it on hand, too, although widespread use among the state’s more than 1,000 districts appears to be uncommon.

The family of Melanie Ramos, the 15-year-old Helen Bernstein High School student who died Tuesday of a possible fentanyl overdose, wants to warn other parents of the dangers of drug use.

San Diego Unified, the state’s second-largest school system after LAUSD, stocks naloxone at schools with students in sixth grade or higher. Since 2020, Elk Grove Unified, a large district in Northern California, has provided naloxone to school security officers and their supervisors.

In L.A. County, the Palos Verdes Peninsula Unified School District recently had a local physician train all the district’s registered nurses on how to administer naloxone and it is available to them at that district’s high schools, said Supt. Alexander Cherniss.

Los Angeles Unified school nurses and school police would learn to administer naloxone, but so could other staff. Carvalho cited the example of an assistant principal who had been a military medic.

“He can do it. He has the training,” Carvalho said in an interview. “I think we’ve maintained a pretty myopic view of who can do this. The training is really not that difficult.”

The decision to distribute naloxone makes sense, said Dr. Gary Tsai, director of substance abuse prevention and control for the county health department, which issued an alert last week about the growing danger of illicit opioid pills.

“Obviously, the best tool is prevention,” Tsai said, but the recent death of the Bernstein student “in and of itself would demonstrate the need to have naloxone on hand,” Tsai said. “It tells you that students have been exposed in one way or another. And the likelihood that they might be exposed on campus, bringing counterfeit pills or come into contact with counterfeit pills on campus, that clearly is a risk. It’s necessary and appropriate for schools to have naloxone on campus.”

A seventh LAUSD student has overdosed from pills possibly containing fentanyl after Bernstein High student Melanie Ramos died last week, LAPD says.

The county health department is providing naloxone at no cost to the district, which also is receiving support in this effort from the Los Angeles Trust for Children’s Health and Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

Initially, the district will have a total of 300 packages, each containing two doses. School police patrols — about 80 cars — will get a package. There will be enough packages for all high schools and likely all middle schools. Carvalho said he is committed to taking on purchase costs as necessary.

Training for district staff in the use a naloxone will begin in early October.

Providing naloxone at schools can be controversial.

Frances Esparza, the former El Rancho Unified superintendent, said she tried to move forward with naloxone training for staff, but “unfortunately, the [school] board majority stated that there was not a drug epidemic in high schools.”

Some parents could interpret naloxone’s availability as a school district giving up on educating students on how to reject drug abuse. Some may fear it will even encourage drug use, said Annette Anderson, deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Safe and Healthy Schools.

But she said parents need to keep in mind what she called an “explosion” in the level of risk, noting that law enforcement reported an increase in the number of illegal opioid pills seized from 300,000 in 2018 to about 10 million in 2021.

Research suggests that students already were facing a mental health crisis prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which made things worse. Such trends underscore the need for additional steps beyond making naloxone available, she said.

“We’re seeing an unprecedented number of violent events happening in schools,” Anderson said. “I think that this is all part of a trend, where our young people are struggling with what it means to cope in modern society. We, as the caring adults, need to be more intentional about how we are connected with our young people, to help them to learn how to problem solve, mediate conflict — basically it’s youth development. All of these issues just really point to how COVID, and COVID school closures in particular, put a pause on our young people’s growth and social development.”

The L.A. Unified announcement also emphasized mental-health and preventive approaches. The Health Information Project organization will be brought in to train high school juniors and seniors to teach health education to their freshmen peers.

“There is nothing better than a student peer to explain the consequences associated with fentanyl to other students,” Carvalho said.

Parents’ awareness about how to recognize and deal with drug abuse in their children will become a major focus of parent education efforts, Carvalho said.

Fentanyl is often mixed with other drugs (including heroin, methamphetamine and cocaine) to increase potency, but it can be deadly. Test kits can help.

The school system already provides drug-abuse education at all grade levels — and it was updated to include the risks of fentanyl. Such course materials and strategies undergo ongoing review, officials said.

Another element of the district response is mapping out where overdoses are occurring and focusing law enforcement resources in those areas, said L.A. school police Chief Steven Zipperman. Officials noted that Lexington Park, near Bernstein High, was a location where the pills containing fentanyl were being sold.

The new rules for higher education require that California community colleges and Cal State campuses supply campus health centers with naloxone. They also require colleges and universities to provide educational materials on preventing overdoses during student orientation.

The law, which also requests similar action from the University of California Board of Regents, goes into effect in January. The legislation “empowers students to prevent any more needless deaths and ensures that maybe one less parent receives a terrible phone call that will change their lives forever,” said State Sen. Melissa Hurtado (D-Sanger), who introduced the measure, in a statement after the bill was signed.

Times staff writers Debbie Truong and Alejandra Reyes-Velarde contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.