California suffering through driest three years ever recorded, with no relief in sight

California’s drought has become the state’s driest three-year period on record, surpassing that of 2013-15 — and a fourth dry year is looking increasingly likely, officials said Monday.

The news came just days after the state began its new water year, which runs from Oct. 1 to Sept. 30. The 2022 water year was marked by dramatic swings between wet and dry conditions and a record-shattering heat wave at the start of September.

With long-range forecasts suggesting that warmer and drier than average conditions will persist, uncertainty remains about what the new water year may bring, even as residents continue to conserve at a commendable pace.

“This is our new climate reality, and we must adapt,” Department of Water Resources Director Karla Nemeth said in a statement. “As California transitions to a hotter, drier future, our extreme swings from wet and dry conditions will continue. We are preparing now for continued extreme drought and working with our federal, state, local and academic partners to plan for a future where we see less overall precipitation and more rain than snow.”

More dryness, extreme weather events and water quality hazards are likely in 2023, state water officials said Wednesday.

The 2022 water year ended with statewide precipitation at 76% of average and statewide reservoir storage at 69% of average, officials said. The reservoir levels are slightly better than last year but still far below normal, as nearly 95% of California remains in extreme, exceptional or severe drought, the three worst categories under the U.S. Drought Monitor.

But historical patterns are increasingly disrupted by human-caused climate change, meaning additional challenges are “getting folded into managing water,” State Climatologist Michael Anderson told the State Water Resources Control Board during a meeting Monday. The 2022 water year began with a notably wet and snowy October through December and was followed by the driest January through March in more than 100 years.

It was a pattern not unlike the previous drought, Anderson said, in which a soggy November and December gave way to one of the state’s driest stretches on record beginning in 2013.

“This year, we outdid that — a decade later, drier and warmer than 2013,” he said. “And that is something else we expect to see: These things we thought would be once in a lifetime, once in a career, are now going to be episodic and may in some instances become commonplace, which will truly be challenging.”

Anderson said the current three-year period is the driest since records began in 1896. What’s more, a stubborn La Niña climate pattern in the tropical Pacific is expected to stick around for a rare third year this fall and winter, he said. La Niña can tip the scales toward dryness, especially in Southern California, but that’s not a guarantee, and much depends on where the system’s high pressure manifests.

“There’s a whole lot of uncertainty right now,” Anderson said.

Officials are lauding the city’s progress, but some experts ponder the long-term plan — especially as seasonal outlooks indicate yet another dry winter is in store for Southern California.

In response to that uncertainty, officials underscored the need for water conservation to remain a “way of life” in California. The state’s residents in August reduced their average water use to 105 gallons per person per day — the second lowest ever for the month, after 2015, when statewide mandates from then-Gov. Jerry Brown drove down usage, according to Charlotte Ely, conservation supervisor at the State Water Resources Control Board.

Residents in August saved 10.5% more water than during the same month in 2020 — the year the drought began and the base line against which savings are measured.

“We’re continuing the trend that we’ve observed since May,” Ely said. “This puts California solidly back on track when it comes to saving water — especially since during the summer, water use usually increases as our irrigation demands increase. These double-digit numbers that we’re seeing really show that people, and the urban retail water suppliers that serve them, are taking these more aggressive actions to curb and reduce water use.”

Some areas are conserving more than others. The South Coast Hydrologic Region, home to Los Angeles, for example, saw 9.7% savings in August, putting it in the middle of the pack, compared with 18% in the South Lahontan region and 3.9% in the Colorado River region.

Cumulative savings since July 2021, when Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a drought emergency and asked all residents to voluntarily cut back on water consumption by 15%, are at 4%, Ely said.

She noted that unless drought conditions improve, a third round of emergency water conservation regulations is likely.

The first regulation, adopted in January, asked residents to monitor water use more closely and prohibited certain wasteful practices statewide, including the use of decorative fountains.

The second regulation, adopted in May, banned the use of potable water on “nonfunctional” grass at commercial, industrial and institutional properties, and ordered urban suppliers to move into at least Level 2 of their water shortage contingency plans.

Ely said a third regulation would probably set standards for residential use indoors and outdoors and identify percent reductions for urban retail suppliers in the state, along with other actions in support of Newsom’s new water plan, unveiled in August.

“One of the things that [Newsom’s] strategy sort of laid out for the world was that hotter and drier conditions spurred by climate change and aridification are expected to reduce California’s water supply by 10% by the year 2040,” Ely said. She said the projection highlights the state’s need to invest in new sources, accelerate projects and make use of new technologies.

Last week, Newsom signed into law Senate Bill 1157, which updates the standards for indoor water use in hopes of saving at least 450,000 acre-feet per year starting in 2030, Ely said. The bill outlines a framework for water conservation that includes establishing 55 gallons per person per day as the standard for indoor residential use until 2025. From 2025 to 2030, that number will drop to 47; after 2030, it will drop to 42.

The latest maps and charts on the California drought, including water usage, conservation and reservoir levels.

Officials on Monday noted that it’s not only urban residents who are facing drying conditions. More than 200 domestic wells dried up in the last 30 days, Drought Response Program Manager Eric Zúñiga told the board, bringing the year’s total of dry wells to 2,031 — a 49% increase over the same period last year.

Experts have noted that drying wells and drought conditions are affecting water quality in the state, as shriveling groundwater supplies can have higher concentrations of pollutants such as arsenic and hexavalent chromium. Nearly 1 million Californians — most of whom are in low-income communities and communities of color — are living with unsafe drinking water.

Jeanine Jones, drought manager at the Department of Water Resources, said many agricultural users also experienced significant cuts this year. The state cut allocations from Feather River water rights settlement contractors by 50%, and the Central Valley Project allocated no water to many of its agricultural contractors. Significant reductions in rice acreage this year could have unintended consequences for birds that rely on flooded rice fields during their fall migration, she said.

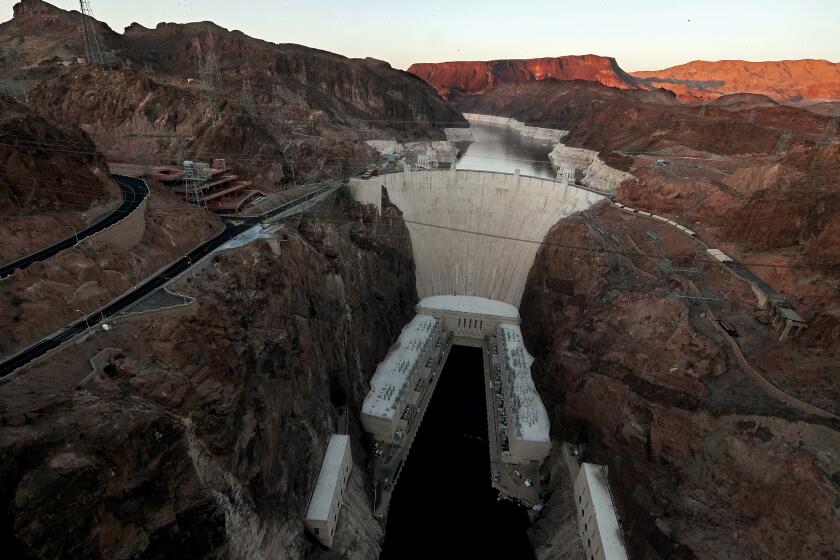

Jones said the challenges don’t stop at state lines. The Colorado River — a major supplier of water for California and surrounding states — is nearing historic lows, and federal officials are putting pressure on the states to significantly reduce their reliance on the river or face painful cuts.

“Realistically, our current drought in the Colorado River basin began in 2000, and this is not something that, on a watershed of this scale, will be recovered from quickly — certainly not just a single wet year, if we were to have that,” she told reporters.

Nemeth, the Department of Water Resources director, said priorities for the 2023 water year will include continuing to meet minimum human health and safety needs, protecting the state’s imperiled fish and wildlife and preserving water quality in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, a linchpin of the state’s system that provides municipal drinking water for millions of people.

“It’s no big surprise that we are planning for a fourth consecutive dry year and certainly discussing the potential for more flood-drought interface in this year,” she told the board.

Board Chair Joaquin Esquivel said the pattern of extremes is making it more challenging to manage the state’s water.

“This kind of dynamism that we’re seeing — where we have these flood events even with general drying and aridity as well — it’s a lot to be watching,” he said. “And really, ultimately, means we have to simply be prepared for both.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.