Jewish communities thrived in early L.A. — and helped the city thrive

There’s an easy formula for sizing up Los Angeles as the destination of choice for the peoples of the Earth: “There are more (nationality/ethnic group) living in Los Angeles than anywhere else on the planet except (that nation’s capital and/or chief population center).”

In the case of the world’s Jews, Los Angeles is not in second place but in third, behind only New York and Israel.

That doesn’t begin to encompass the breadth, the diversity of Jewish Angelenos, who come from Eastern Europe, from Iran, from Russia and Iberia and Morocco and Yemen and Israel itself. And even New York.

They arrived before and after the Gold Rush, the Civil War, the turn of the century, before and after and between both World Wars, and into the 1970s and ’80s and the present day.

The first known among them was a German-born tailor, Jacob Frankfort, who got here in 1841, well before the Gold Rush and statehood. He came overland from New Mexico with a wagon train expedition called the Rowland Workman party; he was a tailor and a rifleman, both handy skills in the new frontier.

We know this thanks to — wait for it — director Cecil B. DeMille. Frankfort’s name, misspelled as “Frankford,” appears in the first U.S. census of Los Angeles. It is a fabulously important and rare document, and here is why we still have it.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In 1915, as Hollywood historian Marc Wanakmaker and other sources recount it, DeMille had leased land on the old Providencia rancho, above the Los Angeles River, not far from many present-day Burbank studios. His crew was clearing rubbish out of an old adobe and burning the stuff when DeMille spotted some old folded papers and fished them out of the fire, or likelier told someone else to do it. They turned out to be the rare — perhaps the only extant — 1850 census for the region.

The same census showed seven later-arriving Jews, all men, and all, according to the Jewish Museum of the American West, owners of dry goods and other businesses in the same building near the old plaza, where they slept in their back rooms. Some of these men and those who followed became the founding fathers of modern Los Angeles, and their businesses became the city’s leading banking institutions and chic department stores, like Hamburger’s and City of Paris.

They came here as so many millions came to California, intent on writing their own futures on what Americans regarded as a blank slate of a place. Former Times reporter and columnist Robert Scheer, in a series from more than 40 years ago on the Jewish community in L.A., characterized them as “a nonreligious, pistol-toting, hustling crowd like their gentile neighbors in this forlorn village.”

“Typically, the Western Jew was a Westerner, and therefore, unlike his Eastern counterpart, determinedly anti-intellectual and bored with big religious and political issues.”

These early arrivals, primarily German and French Jews, founded institutions, charities and philanthropies whose legacies endure today. The 1854 Hebrew Benevolent Society, likely the city’s first formal charity, aided Jews and non-Jews in need. For the price of a dollar, it purchased three acres in Chavez Ravine for the Home of Peace cemetery. When industry encroached at the turn of the century, the cemetery and its 360 graves were moved to East L.A. The names on the gravestones are a roster and a history of Jewish L.A., its past and its future fortunes: members of the Laemmle family, all three Warner brothers, MGM co-founder Louis B. Mayer, at least two of the original Three Stooges and Solomon Lazard — City Council member, head of the Chamber of Commerce and member of the international banking family.

The Kaspare Cohn Hospital, begun in 1902 to treat Jewish tuberculosis patients in a house in Angelino Heights, was the forebear of today’s immense Cedars-Sinai medical network. Not long thereafter, the Workmen’s Circle, a cooperative association of Jewish workers, was organized in 1909; it created institutions to serve poorer Jewish emigres arriving in numbers from eastern Europe. Among them was a TB sanitarium that became the seed for today’s City of Hope, the renowned cancer treatment and research center.

Among the “gratin” Scheer mentioned was the Newmark family of Prussian Jews. Harris Newmark — who like his family was deeply enmeshed in the city’s cultural, political and charitable, life arrived here in 1853 and helped to found the city’s library and the Southwest Museum. He left a huge memoir, “Sixty Years in Southern California.” One of its footnotes proudly quotes his friend George W. Burton, another civic figure, saying that Newmark’s Jewishness “was an advantage in one way, and a handicap in another; it was an advantage to a young man giving him a sound mind in a sound body, and a disadvantage in the prejudices entertained against many in this ancient race.”

Newmark’s book spoke admiringly of the racial multitudes he knew here in L.A., but the historian David Samuel Torres-Rouff, in his book “Before L.A.: Race, Space, and Municipal Power in Los Angeles, 1781-1894,” puts rose-colored glasses on Newmark, suggesting that his status in a founding family of modern L.A. gave him an “amnesia” about the city’s failings and easily obscured its vicious and violent history, in part because Newmark wasn’t the target of it.

At first, an early ecumenicalism and pull-together civic spirit for an emerging L.A. helped to welcome Jews in the city’s life. Around the Civil War, both Jewish and Protestant kids attended a Catholic parochial school. L.A.’s first official rabbi, Abraham Wolf Edelman, arrived in 1862, about 10 years before the first synagogue was built. Jews’ earliest meetings were held in public halls and even in Judge Ygnacio Sepulveda’s courtroom.

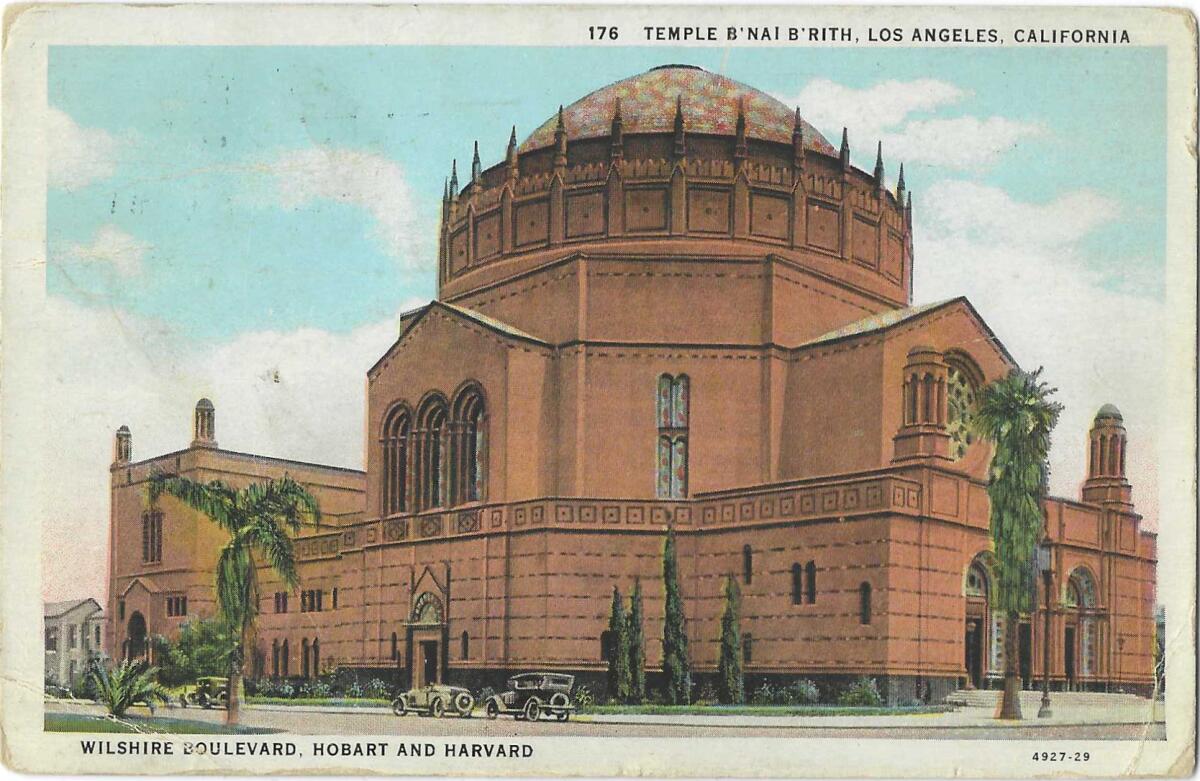

Making common spiritual cause with the city’s faiths and its leaders has been a hallmark of Judaism in Los Angeles. The magnificent Wilshire Boulevard Temple was built and presided over by Rabbi Edgar Magnin, a California native and for nearly 70 years head of the city’s oldest Jewish congregation.

So ardent was Magnin in his belief in interfaith spiritual leadership that his nickname was “the Cardinal.” It was the work of men and women like Magnin that helped to forge the coalition that elected Tom Bradley, the sharecroppers’ son from Texas, as L.A.’s first Black mayor.

It’s yet to be determined if Karen Bass will break the long string of men who have held L.A.’s highest elected office. Here are the stories of other women who have run for mayor or briefly served.

One of L.A.’s prominent Jewish businessmen was the French-born Marc Eugene Meyer, whose son, Eugene, was born here, and was closely related to the Newmark and Lazard families. Young Eugene left California for the East Coast and became a financier, a Fed chairman and owner of the Washington Post, which was in time run by his legendary daughter Katharine Graham.

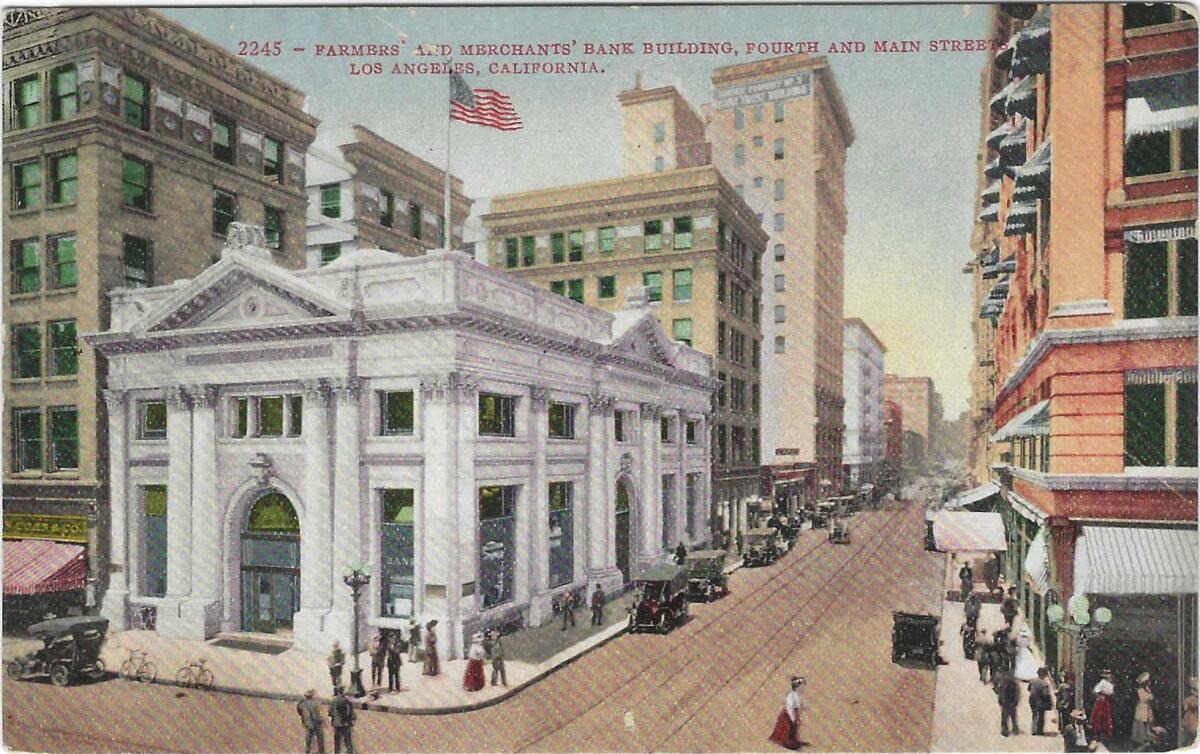

Perhaps the most celebrated of them all was Bavarian-born Isaias W. Hellman, who, with California’s first American governor, founded L.A.’s first thriving bank, the Farmers and Merchants bank.

In her biography of him, “Towers of Gold,” his great-great-granddaughter, Frances Dinkelspiel, explained that “in a time of unsophisticated financial markets, when banks minted their own money, bankers like Hellman were the men who smoothed the rough edges of the economy … bankers offered stability.”

For the record:

12:05 p.m. Nov. 30, 2022A previous version of this article misspelled the last name of journalist and author Frances Dinkelspiel as Dinkenspiel.

Hellman helped to bankroll The Times’ founding publisher Harrison Gray Otis, and oilman Edward Doheny. He partnered in Henry Huntington’s streetcar venture, financially backed the Los Angeles Aqueduct project and helped to bring the Union Pacific to town. He joined other men to donate the land for USC.

For all that Hellman was vital to the prospering of the city — and, as Dinkelspiel wrote, “exemplified the almost unfettered access Jews had to power” — his Jewishness, and how attitudes toward Jews could turn on a dime, still seemed to be top of mind to him. Hellman once told his bank’s attorney, Jackson Graves, “I have to be a better man than you are, because I am a Jew. You can do things that I cannot do. If I did them, I would be criticized, while you would not be.”

One of Hellman’s real estate holdings was a neighborhood called Boyle Heights. Toward the end of the 19th century, Jewish merchants began building homes there to be close to downtown yet above it, at a cooler altitude.

In time, and until after World War II, Boyle Heights was the nucleus of life for most L.A. Jews. Almost two dozen synagogues served as many as 60,000 Jews. One of the rare surviving buildings is the Breed Street Shul, for decades the largest Orthodox congregation in the West. It’s being preserved as a national historic site and as a center for multicultural events and audiences, like “Fiddler on the Roof” sing-alongs, and a community tree planting.

By the 1980s, most of L.A.’s Jews had moved west, to the Fairfax district or the Westside, or to the San Fernando Valley, and Boyle Heights’ last synagogue had a hard time mustering a minyan, the quorum of 10 required for a service.

In 2013, Eddie Goldstein, whose family regarded him as the last Jewish man to be born and to stay on in Boyle Heights, died in 2013, mourned by his Mexican American wife’s vast family — the perfect-pitch note of this new, changing L.A.

These newly arrived Jewish immigrants of the 20th century were different in many ways from the German and French Jewish Angelenos of the 19th century.

Joseph S. O’Flaherty, writing 30 years ago in “Those Powerful Years” about the rise of Los Angeles to prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, argued that “the prosperous Los Angeles Jewry of the 1890s was embarrassed by the first influx of persecuted eastern European Jews, particularly Russian, who had fled the pogroms, arriving ... with no money, decidedly foreign mannerisms and a substantial language barrier.” They survived by opening second-hand shops and pawn shops that reinforced “stereotyped prejudices.”

The doors that had been opened to their 19th century predecessors were closed to the newcomers. Politics, especially socialist politics, mattered to them, and the vigorous organizations they created were often working-class and more political than religious.

“There were actually two Los Angeles Jewish communities,” wrote Scheer, “composed, on the one hand, of the older German Jews and, on the other hand, of the newer East European immigrants.”

Yet in the eyes of antisemites, they were all the same: all Jewish, and all suspect.

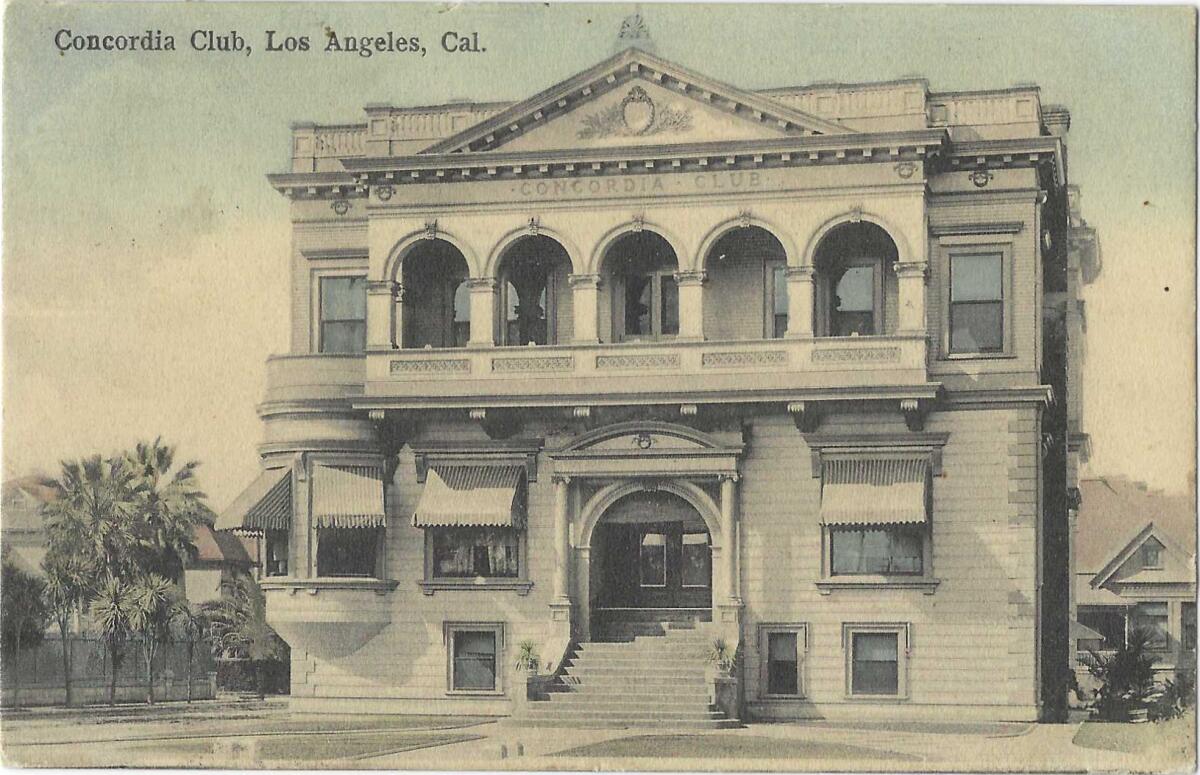

In a town powered by real estate, restrictive covenants barring real estate sales not just to Black and brown people but also to Jews now appeared on deeds. Clubs that had once welcomed Jews no longer did. The exclusive California Club had had Jews among its founding members in 1888. In a few decades, they were no longer welcome. Not until 1976 was a Jew again admitted — Harold Brown, the U.S. Defense secretary and former president of Caltech. Jews were excluded from country clubs and so, in 1920, created the Hillcrest Country Club, not far from Fox Studios. L.A.’s Jewish “first families” formed the Concordia Club in 1891, and it survived until about 1915.

Except for the Hollywood studios often founded and run by Jewish businessmen and creators — about whom whole forests’ worth of books have been written — “the Jew,” as The Times wrote in 1969, “is strangely missing, or rarely seen, in another elite quarter of American life — the executive suite of the big business or industrial corporation.”

The surge of fascism and antisemitism reached its fingers across from Europe into Southern California, where fascists like the German bund and Hitler agitators like the Silver Shirts were openly strident.

In “A Cultural History of Jews in California,” Shana Bernstein wrote that twice in September 1935, tens of thousands of copies of an antisemitic pamphlet were slipped into home editions of The Times, pasted up around town and dropped into cars. Some Times employees had sneaked them into the papers, evidently without the knowledge of management.

The repugnant pamphlets ranted about Jews’ “unspeakably bestial degeneracy,” about what would now be called “grooming” of Gentile girls, and that Jews “promoted a widespread contempt for the virtues of honor and honesty in business.” This happened the very same month that the Nazis’ hate-steeped Nuremberg laws were enshrined in Germany.

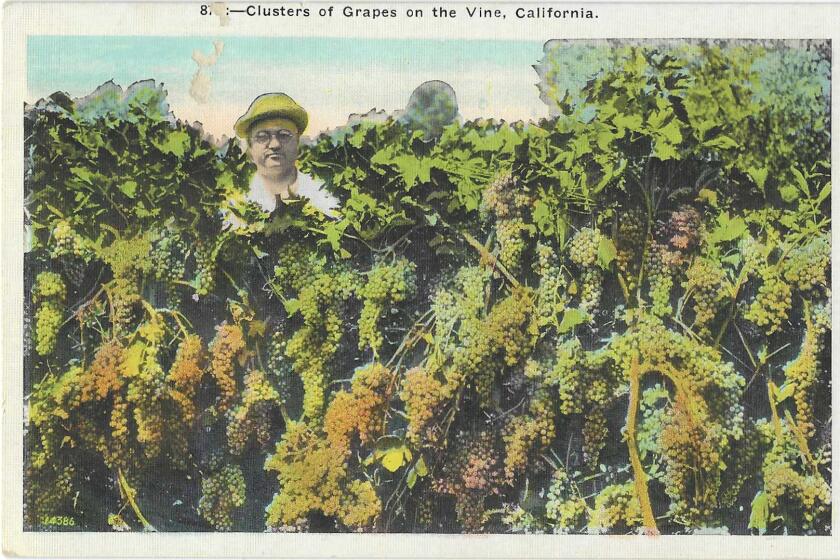

Next time you raise a glass of California wine, remember the time when Los Angeles, not Northern California, was the state’s major wine region.

In 1933, as more doors to business and civic and philanthropic leadership were being closed, Jews formed a Community Relations Committee to monitor antisemitic activities. USC professor Steven J. Ross’s book “Hitler in Los Angeles: How Jews Foiled Nazi Plots Against Hollywood and America” thoroughly details what L.A. Jews did when neither the LAPD nor the FBI seemed to care to keep an eye on Southern California Nazis — although once the U.S. was attacked at Pearl Harbor, both agencies asked the committee for its files.

From the late 1920s until the Pearl Harbor attack, the Jewish population of L.A. pretty much doubled, to about 130,000. The newer Jewish Angelenos were impelled to immigrate more by persecution, especially in Eastern Europe, than by the opportunities that had drawn earlier Jewish settlers here.

They were more ardent in their politics than their predecessors, too, having witnessed how politics could be manipulated by the Nazis, and having been galvanized by the creation of the state of Israel.

Younger and newer Jewish Angelenos blazed different paths.

Take Zev Yaroslavsky — his first name means “wolf” in Hebrew, and his Zionist parents founded the City Terrace Folk Shule in the 1930s. Yaroslavsky pulled off inventive protests in the early 1970s that helped to carry him to the Los Angeles City Council and later the L.A. County Board of Supervisors.

He and other young activists wanted to protest the Soviet Union’s ban on Jews immigrating to Israel. When a Soviet freighter docked in L.A. Harbor, Yaroslavsky and a friend rented a small boat and headed for the huge ship, planning to paint “Let the Jews Go” on the side.

But their boat kept drifting away, so one of them thwacked a toilet plunger to the side and held on while the other managed to paint a Star of David and “LET JEWS GO.”

The dignified Isaias Hellman would never have done such a thing — but in his heart, he might have wanted to.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.