L.A. Unified, California showcase record graduation rates; other measures show setbacks

The state of California and the Los Angeles Unified School District achieved record-high graduation rates last year despite the lingering effects of the crippling pandemic and a historic spike in student absences, prompting both praise and skepticism over the new numbers.

For the high school class that graduated in 2022, the percentage of students who earned a diploma in four years in Los Angeles Unified — the nation’s second-largest school system — was 86%. The rate for all of California was 87.4%. The graduation figures were released this week.

For the record:

11:53 a.m. Dec. 17, 2022And earlier version of this article included a photo caption that incorrectly said Panorama High School is in the San Gabriel Valley. It is in the San Fernando Valley.

For the state, this figure was a nearly 4 percentage point increase from the 83.6% rate of the 2020-21 academic year. For L.A. Unified, there was about a 4.5 percentage point increase from 81.6%, a continuation of an ongoing trend of annual graduation-rate increases.

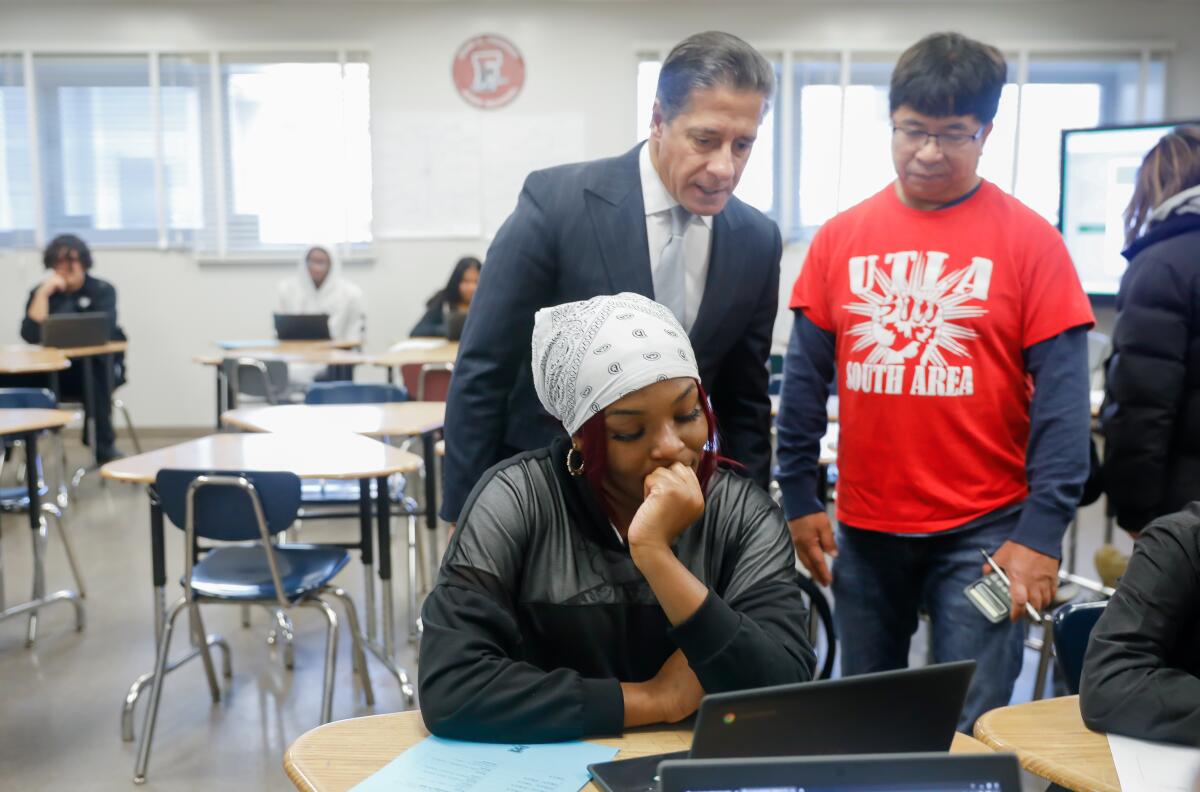

L.A. schools Supt. Alberto Carvalho called the graduation rate “historic” and “precedent setting,” and noted that, in general, the greatest gains were among Black students, students learning English and students with disabilities — groups with lower rates historically than white and Asian students.

“That means our teachers are delivering. Our principals are leading. The right support systems are in place,” Carvalho said Thursday.

But others greeted the positive numbers with restraint.

“While I am pleased to see the data showing that students are doing well academically, it completely flies in the face of data that suggests students had fallen behind due to the pandemic,” said Tyrone Howard, professor of education at UCLA’s School of Education & Information Studies. “It would be good for LAUSD to help the public understand the two narratives and how they coexist... It is a big disconnect that is hard to comprehend.”

2022 California test scores show 84% of Black students and 79% of Latino and low-income students did not meet state math standards.

The praise from Carvalho and others was intended to credit updated instructional methods, as well as the hard work and resiliency of students, teachers and administrators who have endured through the COVID-19 pandemic. The skepticism is rooted in concerns that higher graduation rates may be linked to ongoing relaxed standards combined with pandemic-inspired compassion.

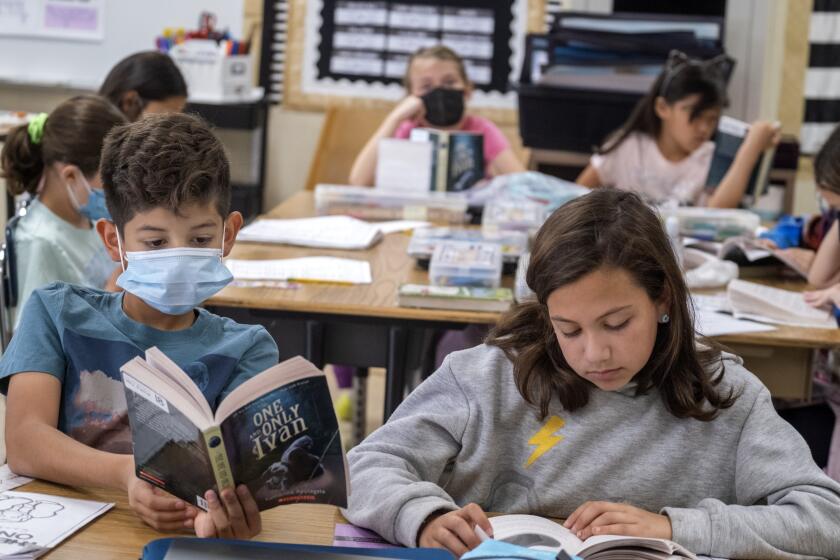

The new numbers follow a string of academically debilitating events in schools. The COVID-19 pandemic led to campus closures and remote learning from home in March 2020 — with most Los Angeles students not returning to in-person instruction until the fall of 2021.

And, when students did return, illness and quarantines resulted in widespread chronic absenteeism. These figures also were released this week.

A student who misses 10% or more of the school year is classified as chronically absent. Statewide, chronically absent students increased from 14.3% of enrollment in 2020–21 to 30% in 2021–22.

In L.A. Unified, the rate of chronic absenteeism last year was 39.8%, including a 52.7% rate for Black students.

Although official attendance figures were better the prior year — when most students learned online for all or much of the year — student engagement was a serious problem that relaxed accounting methods did not capture.

In L.A. Unified and, apparently, many other California districts, if a student — or a parent — sent an email or text or talked to a teacher on the phone at any point in the day, the student was counted as present.

Moreover, if a student appeared in a live session with a teacher or classmates on Zoom, however briefly, the student was counted as present for the entire day.

L.A. Unified also eased grading standards.

The lessened requirements were in large measure a recognition that students had to cope with technology problems and family stresses at home.

The shortcomings of remote instruction, and also of in-person instruction, interrupted by absenteeism, resulted in predictable harm to learning — according to study after study. Carvalho has previously acknowledged as much, saying that five years of progress as measured through increases in state test scores was wiped away.

The alarming dip in math proficiency and smaller declines in English in the last two pandemic-disrupted school years hit students who were already behind.

Graduation rates, however, went in the other direction.

Part of the explanation is that completing a course does not equate precisely to learning. And, attention to academic rigor goes through cycles. State lawmakers created a high school exit exam in 1999 to guarantee that every student with a diploma could meet minimum academic standards, but the test later was done away with as unfair and unnecessarily punitive.

The state sets minimum graduation standards in terms of the classes that must be passed — and districts, including L.A. Unified, have often added additional required classes.

During the pandemic, however, state officials suspended all but the minimum state requirements, which could have resulted in more students earning diplomas, the state education department acknowledged this week.

L.A. Unified was unable to say this week whether any of its graduates crossed the finish line because of the reduced diploma standards.

California and Los Angeles reflect a national long-term trend of rising graduation rates.

In the 2018-19 school year, the latest available national data, the graduation rate for public high school students was 86%, the highest since the rate was first measured by current methods in 2010–11, when the rate was 79%.

In recent years, record graduation rates for L.A. Unified have been a regular occurrence. Educators have worked harder to identify struggling students early on and provide specialized help, especially for Black students. There has also been scrutiny toward identifying specific topics and assignments that are preventing students from passing a class — and allowing students to address the specific learning obstacles without having to retake an entire class.

Online credit recovery allows students to make up classes quickly — although the rigor and test security of these courses have been questioned.

“It’s tough to know what a high school diploma represents right now,” said Robin Lake, director and professor of practice at the Center on Reinventing Public Education at Arizona State University.

“I am glad these students have a degree under their belt,” Lake said in relation to the L.A. Unified numbers. “The current and recent graduating classes have been through so much. However, it is hard to square the uptick with the fact that 81% of LAUSD 11th-graders didn’t meet grade-level math standards last year and the fact that the district saw deep setbacks in scores across student groups and across grade levels.”

“Either something truly miraculous happened last year on behalf of LAUSD’s class of 2022 or they were handed a degree and ushered out of the K-12 system largely without the skills and knowledge they’ll need to thrive in college and in life.”

UCLA education professor John Rogers preferred a glass-half-full interpretation.

“Students in LAUSD did not have the same access to quality learning during remote learning as they do now that they are in person — and this did affect the academic and social development of many young people. But I still am inclined to celebrate these outcomes,” he said.

“Students who experienced the extraordinary disruption of the pandemic and persisted in graduating — and graduating college-eligible — are able to continue their learning in higher education where they will be able to make up for experiences lost even as they grow further.

“Yes, this might place additional challenges on our higher education system,” he added, “but that is a challenge we can and should meet.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.