SAN YSIDRO, Calif. — The phone calls started coming into the immigration support hotline in October 2018, many from the McDonald’s at the San Ysidro pedestrian border crossing.

Groups of asylum seekers had been left there by U.S. border officials, the result of a policy change in how the government dealt with migrants released from custody. Most didn’t have any way of contacting their relatives across the United States, let alone getting to them. They were hungry and tired and had nowhere to sleep.

Volunteers with the San Diego Rapid Response Network soon found themselves spending cold nights at bus stations, looking for asylum seekers who had been similarly dropped off and abandoned by the U.S. government.

The various organizations that made up the network quickly mobilized to create a temporary shelter space. It moved five times over the next several months, borrowing spaces from churches and nonprofits until it found a longer-term home through support from San Diego County and the state of California.

Kate Clark, an attorney with Jewish Family Service who was instrumental in setting up and managing the shelter, would often say the work was like learning to build an airplane while it’s already in the air.

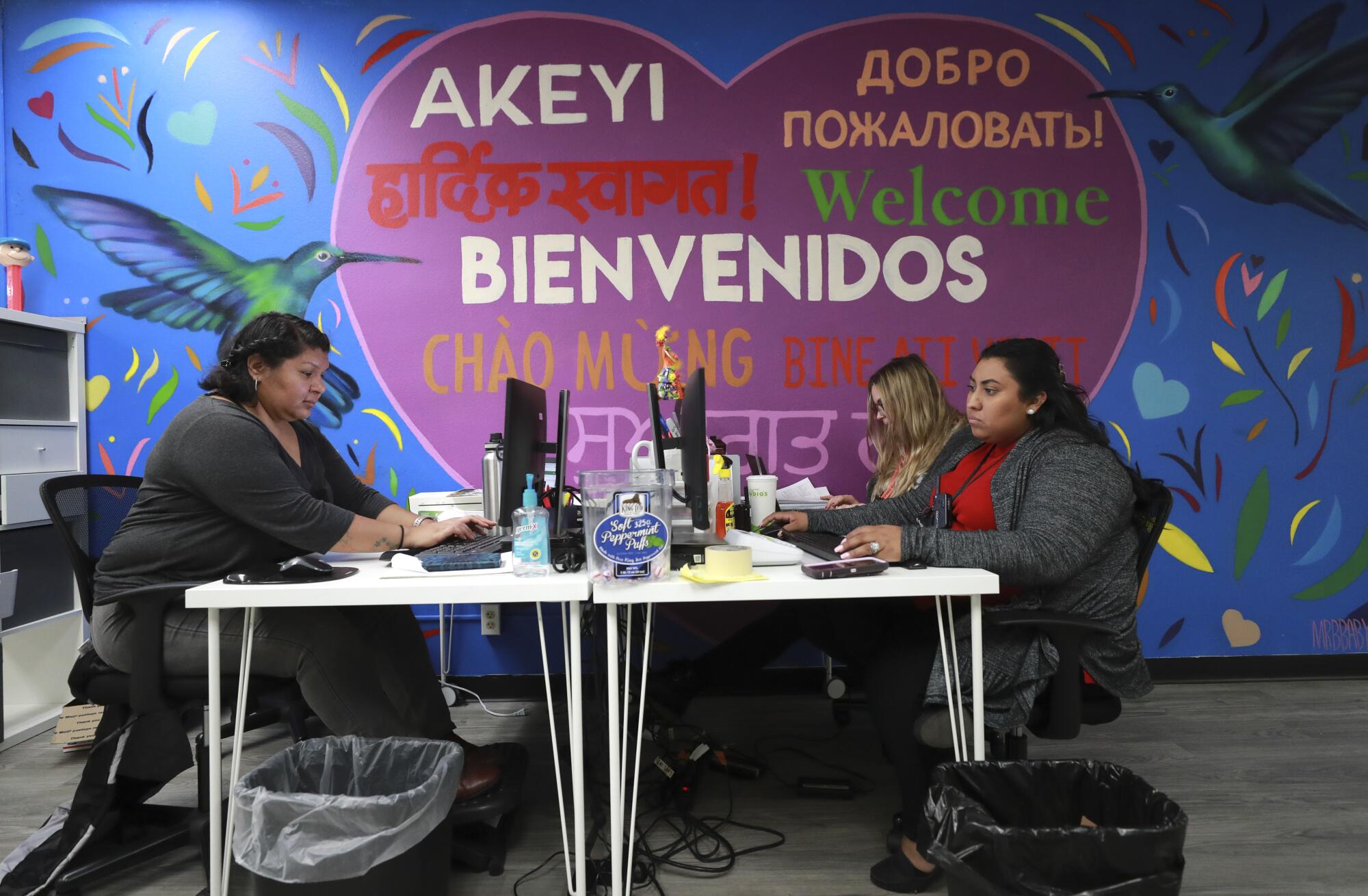

No one around for that chaotic beginning knew they would still be doing this work four years later. But now the San Diego Rapid Response Network Migrant Shelter, run by Jewish Family Service, has become a major institution at the San Diego border that helps asylum seekers who have been released into the United States reach their family and friends around the country.

That experience will likely make the shelter an important player as the potential end of Title 42 — a border policy that limits who can reach U.S. soil and request protection — approaches in the coming week.

The shelter has already become a model for nonprofits along the border — and more recently in cities throughout the country where asylum seekers were randomly bused by Republican governors.

“They are the gold standard,” said Naomi Steinberg of HIAS, an international nonprofit that supports refugees. “They have really shown organizations around the country about how it can be done and how it should be done.”

One of the operation’s key strengths, according to many who have worked with it, has been its ability to adapt its entire operation on short notice to the changing needs of the border.

That it’s had to adapt is evident when considering whom the shelter has served over the past four years, trends that reflect the changing landscape of U.S. border policy and events around the world that have caused people to flee their homes.

“That’s part of the challenge,” said Norma Chávez-Peterson, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of San Diego and Imperial Counties, one of the partners in the network. “We’ve been constantly reacting to really inhumane policies and the politics of the border.”

In early November, almost exactly four years after it opened, the shelter welcomed its 100,000th guest.

“I don’t think that any of us at Jewish Family Service could have imagined, saw the crystal ball, knew what was in the crystal ball,” said Michael Hopkins, executive director of Jewish Family Service. “We just knew back then four years ago that it was the right thing to do at the right time.”

Caring for well-being

When Yolanda, 31, and her four children escaped from Michóacan, a state in Mexico that many are fleeing because of cartel violence, they spent the first night in Tijuana outside a migrant shelter that was too full to receive them. She is not being fully identified due to ongoing safety concerns.

A few days later, they were able to enter the Tijuana shelter and sleep on a mat on the floor until a bed opened up for them to share. One of her children slept on the floor because they didn’t all fit. They spent nearly four months that way until they were picked to enter the United States through a temporary program for certain asylum seekers.

When she arrived at the San Diego Rapid Response Network Migrant Shelter, she became the 100,000th asylum seeker received and cared for by the organization.

Before the pandemic, most shelter guests slept on cots in large dormitories, but to mitigate COVID-19 concerns, the shelter has converted to rented hotel rooms.

When Yolanda walked into her hotel room, she noticed, above all else, that it was finally quiet. She noticed, too, how the stress of the last four months disappeared with the noise. Her children relaxed seemingly overnight with help from the two big beds that they fit easily into.

“It was a happiness to be here,” she said in Spanish. “I feel safe. I’m here. They can’t do to me what they did in the past.”

She took a hot shower for the first time in months.

Many guests have shared similar stories with the Union-Tribune over the years — the little details that made them feel more human than they’d felt in a long time.

“We pride ourselves on holistically serving all of our guests in a culturally competent, trauma-informed way,” said Clark, the attorney with Jewish Family Service who helps manage the shelter.

That meant that when arrivals shifted to Ukrainians fleeing Russia’s invasion of their country earlier this year, the shelter had to find people to help who spoke Ukrainian.

It also meant that in 2019, when Border Patrol sent people who had the flu on planes from Texas and they ended up at the shelter, the medical team from UC San Diego was ready to respond. The team was then able to adapt its protocols after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure the safest possible conditions for arriving asylum seekers as well as the general public.

Dr. Linda Hill, assistant dean of the School of Public Health at UC San Diego and executive director of the asylum seeker medical screening and stabilization program, recalled being asked by the county in 2018 to put a program in place with 24 hours’ notice shortly after the shelter began operating. Her team had to create protocols that worked for the kind of space they were in. The program started on Christmas Eve.

“We’re not trying to solve all their problems. We can’t. We’re screening and stabilizing,” Hill said. “But we want to do our part to contribute to their overall well-being.”

Building a network

In some ways, the backbone of the shelter was born in 2017 at a community meeting among activists at a church in Barrio Logan. They were concerned about an increase in immigration enforcement in San Diego’s communities of people here illegally under the Trump administration.

The result was a hotline that people could call if they or their neighbors were experiencing an immigration arrest.

Then, the hotline began receiving calls about asylum-seeking women and children stranded on the streets of San Diego. Immigration officers were no longer helping asylum-seeking families with their travel plans before releasing them from government custody after they crossed the border. The various organizations from across the county that were a part of the Rapid Response Network built on their existing collaborations to respond.

That coordination and communication are another of the shelter’s lessons.

At the beginning, many of the organizations sent staff to work in the shelter. Chávez-Peterson recalled sending her executive assistant and the ACLU’s front desk staff to help. As the shelter built up volunteers, and later paid staff, the myriad organizations have stayed involved to offer support where needed. That has helped with the shelter’s adaptability.

The shelter also developed a relationship with Customs and Border Protection to coordinate dropoffs, to avoid having asylum seekers left in the street.

“How do you address an issue? You solve an issue working together,” Chávez-Peterson said. “It can’t be this victimizing, pointing fingers or evading responsibility.”

Local and state governments also collaborated with the shelter to offer locations to stage the shelter in different moments. Currently, both the state and federal governments provide access to funding.

The collective of organizations have different kinds of expertise — including legal, medical and advocacy — which also allows the shelter to offer diverse services to asylum seekers.

The shelter and its affiliated organizations have used information from its guests to advocate on a broader scale for asylum seekers whose rights may have been violated by the U.S. government. Concerns brought to light by the team have led to investigations into the treatment of pregnant women in immigration custody as well as the reunification of separated families.

Adapting to changes

For most of the past four years, the shelter has been the main place where people have gone after crossing the San Diego-Tijuana border if they were released from immigration custody into the United States. Catholic Charities more recently opened a second San Diego shelter to receive asylum seekers from the border.

However, most people apprehended in the San Diego area in the last four years did not then get released into the United States. If they had, the Rapid Response Network shelter could have reached 100,000 guests long before now.

From November 2018 through September 2022, the shelter received just under 100,000 people. Meanwhile, border officials at and between ports of entry made nearly 600,000 apprehensions, according to data from Customs and Border Protection.

Catholic Charities did not provide similar data for its shelter when asked by the Union-Tribune.

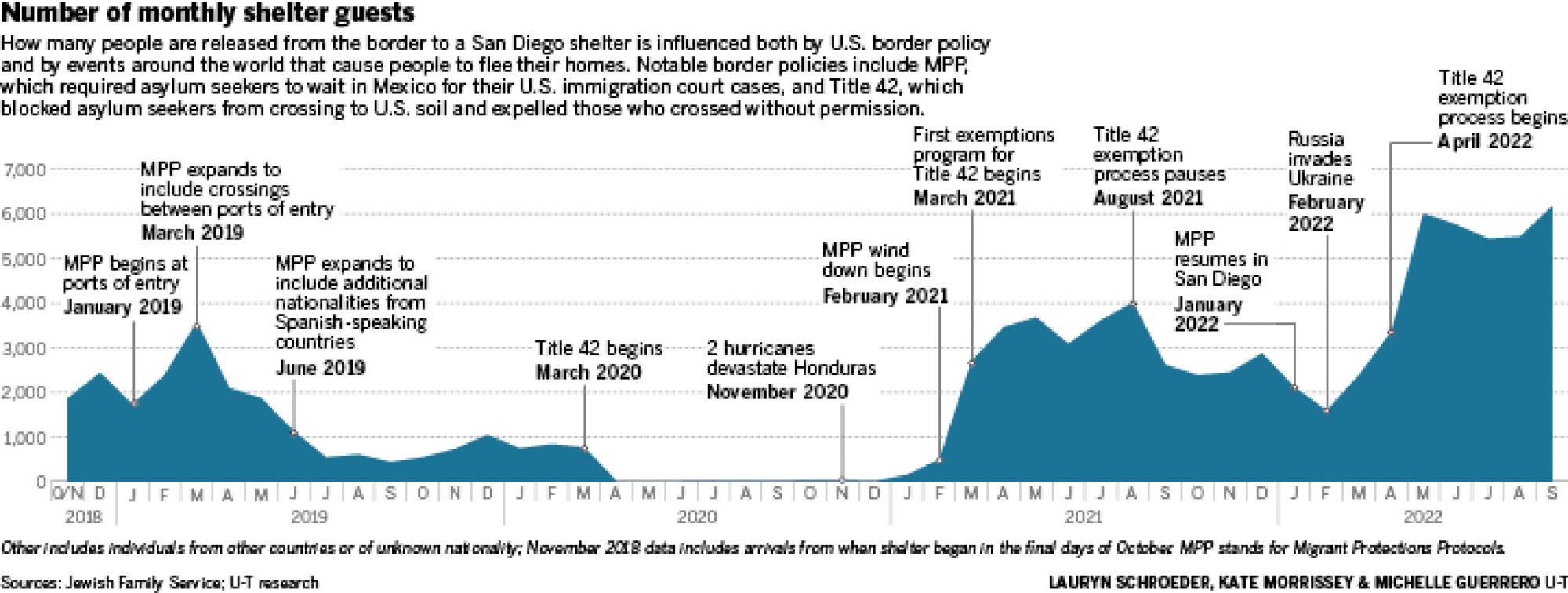

Federal restrictions put in place to cut off asylum seekers’ access to U.S. soil dramatically reduced the number of monthly arrivals to the shelter.

From the shelter’s inception, the number of monthly guests initially peaked at more than 3,500 in March 2019 before dropping because of the “Remain in Mexico” program, known officially as Migrant Protection Protocols or MPP. Through the program, border officials required asylum seekers from certain countries to wait in Mexico for their U.S.-based immigration court cases to proceed. That meant those families were no longer released into the United States.

As the Remain in Mexico program ramped up from January through June 2019, the number of asylum seekers released into San Diego decreased significantly. The shelter received just over 400 people in September 2019.

Though arrivals increased moving into 2020, they plummeted again after Title 42 was introduced in March. That policy blocked asylum seekers and other undocumented individuals from coming onto U.S. soil, and if they did so without permission, Title 42 gave officials the power to expel them without considering their requests for protection as is normally required by law.

In May 2020, for the first time since it opened, the shelter didn’t receive any guests. A few dozen people came over the following months before arrivals began increasing again in 2021.

Though Title 42 remained in effect, conditions in many countries in the Western Hemisphere had grown more dire over the course of the pandemic. Because of logistical constraints, certain nationalities were not able to be expelled easily. As the demographic of border crossers shifted, more asylum seekers arrived to the shelter, requiring a quick ramp-up of services and staff.

“I’ve often said the folks that we’re serving are the lucky ones,” Clark said. “It’s not lost on us as a cross-border legal service provider to know very clearly who is not coming to us.”

The shelter’s data-tracking system changed over time, and nationality information became available beginning in January 2021. Since then, Russians have been the largest group received by the shelter, followed by Mexicans, Hondurans, Haitians, Colombians and Brazilians.

Regardless of where the guests are from, shelter staff notice similar transformations that happen in many from the moment they arrive to when they leave for the next step of their journeys.

Luis Gonzalez, an attorney with Jewish Family Service, said he’d seen the difference in one of his clients, a young boy who had witnessed his mother getting raped when they were on their journey to the U.S.-Mexico border to request asylum. After they reached the border, they were sent back in the Remain in Mexico program. With Gonzalez’s help, the family was eventually taken out of the program and released into San Diego.

“You could tell just by looking at his eyes that that little boy, there was just something about him that was just gone,” Gonzalez recalled, growing emotional. “Once we got him to the shelter after being detained for so long you could see a change, and you could see that he was feeling better. We were not able to prevent what he went through, but we were able to get them to a point where they were safe. I was able to see the before and then I was able to see that relief in his eyes.”

Thousands more like him and his mother are still waiting to reach U.S. soil and request protection.

The government has not yet made clear what will happen if Title 42 actually ends. In the meantime, Clark and her team are working to make sure they’re ready to adapt again.

“We’re very clear that this is going to take all levels of government to be able to safely receive and serve folks that are released into the community. It’s going to take all of us — along with what we’ve learned along the way,” Clark said. “No one organization can do this alone, no one level of government.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.