Column: 2022 was the year Latino politicians became the ultimate villains

Until I joined The Times four years ago, I cared as much about Los Angeles politics as I did the Peoria City Council.

I knew the biggest names, of course — Bradley, Gates, Yaroslavsky, Garcetti, even Joel Wachs. They were inescapable, broadcast to my home every night via television and printed in the pages of this newspaper every morning.

But I’ve lived my entire life in Orange County, so the day-to-day business of L.A. politics was just background noise. L.A. City Hall didn’t register with my relatives in East Los Angeles, Montebello and the San Gabriel Valley either.

Yet I still looked to L.A. for inspiration, through the Latinos who made history with every election they won.

Gloria Molina, the first Latina to become an L.A. City Council member and county supervisor. Antonio Villaraigosa, the first Latino mayor of Los Angeles in 130 years when he won in 2005. Jose Huizar, born in the rancho between my parents’ villages, who became the first Mexican immigrant elected to the L.A. City Council. Hilda Solis, an Assembly member turned Congress member turned U.S. secretary of Labor turned first Central American elected to the L.A. County Board of Supervisors. Kevin de León and Gil Cedillo, immigrant rights organizers who continued their righteous campaigns in the California Legislature before joining the L.A. City Council.

In Orange County, the few Latino politicians were mostly egomaniacs who sold out their community at the drop of a developer donation. I felt that L.A. Latino politicians were above that. They were paragons of the community that forged them, examples of what Latinos could do if only we could get political power.

There were some bad apples — Councilmember Richard Alarcón and his residency issues, corruption-ridden southeast L.A. County cities like Bell and South Gate, Huizar and the federal bribery charges against him. But most of the critiques I heard against L.A. Latino pols in the media and from friends seemed like racism, sour grapes or gripes from liberals who didn’t know how good they had it compared with a truly oppressive place like O.C.

When I began to cover L.A. for this paper and reached out to those political pioneers, I was flattered if they said they liked my work down in O.C. As other Latino politicians assumed important posts — Xavier Becerra joined President Biden’s Cabinet as the secretary of Health and Human Services in 2021, the same year Alex Padilla became California’s first Latino U.S. senator — I held hope that 2022 would bring even more positive milestones.

Oh, how wrong I was. It was an annus horribilis for Latino politicians in L.A.

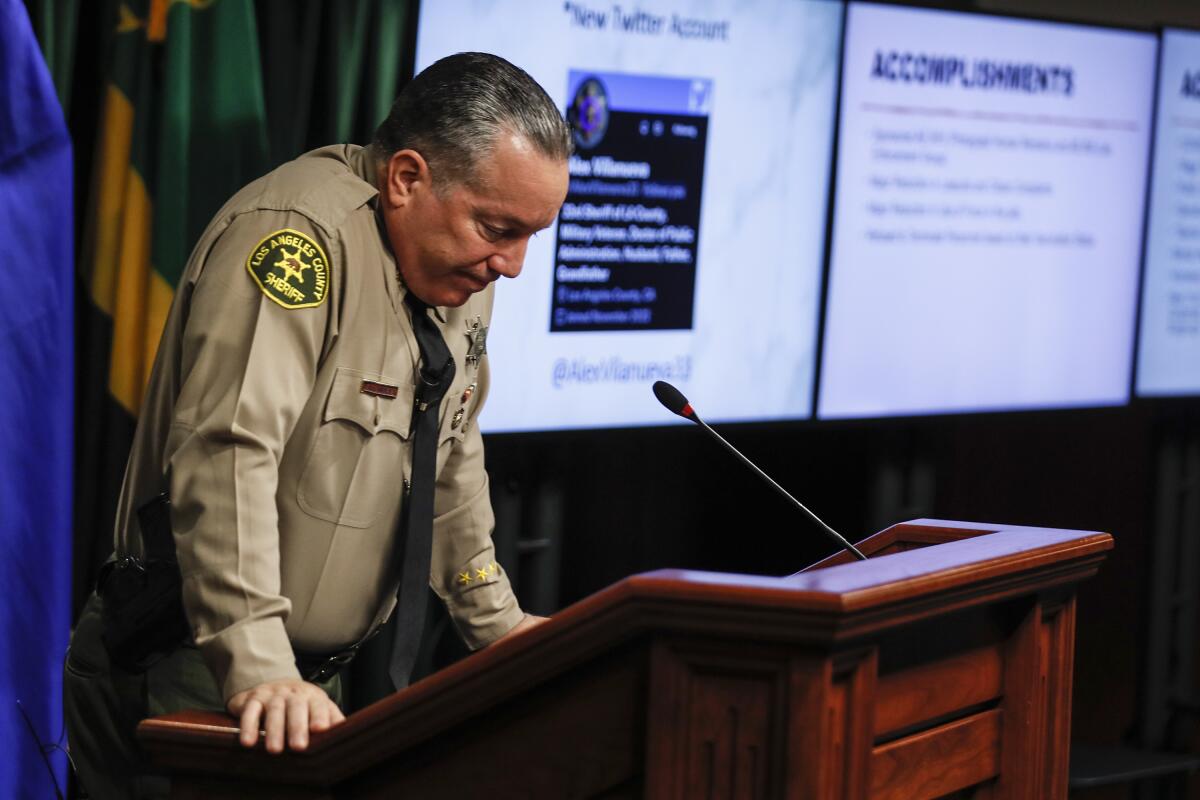

L.A. County Sheriff Alex Villanueva — who made history in 2018 by defeating an incumbent with the help of Latina luminaries like Molina and labor legend Dolores Huerta — became a national poster boy for everything wrong with law enforcement and suffered a humiliating loss to challenger Robert Luna. Cedillo, a Chicano warrior if ever there was one, lost his reelection in the June primary to a political novice, Eunisses Hernandez. More embarrassing revelations came out about Huizar, who awaits trial.

And then there was the secretly recorded 2021 conversation between Cedillo, De León, then-L.A. City Council President Nury Martinez and then-L.A. County Federation of Labor President Ron Herrera that leaked this fall. Their cackling machinations to keep their seats and punish opponents, all while insulting Black people, Oaxacans and others, made the very idea of Latino political power a four-letter word.

Since then, they have only made matters worse. Martinez, the first Latina to become L.A. City Council president, ended her resignation letter with a tone-deaf shout-out “to all little Latina girls across this city,” hoping that “I’ve inspired you to dream beyond that which you can see.” Cedillo finished his term this month with his own defiant statement slamming critics for allegedly practicing cancel culture “at its worst” and tauntingly concluding with, “This kid from Boyle Heights never resigned.” De León continues to ignore calls to step down, arguing that only someone like him can help his mostly Latino constituents.

They, along with Huizar and Villanueva, did what bigots long claimed would happen if Latinos ever got the keys to power: They would screw up hugely. Now, the most loathed politicians in Los Angeles are Latinos — and the hate against them is warranted.

With embarrassments like them, who needs Latino politicians?

That’s the speck of hope in the dumpster fire that was 2022. In an era in which identity politics seems to govern the ballot box more than ever, this year should serve as a reminder that the best person to represent you sometimes isn’t going to look like you.

And sometimes, the worst person to represent you looks just like you.

Latino representation in government is important, especially in a city and county that’s nearly 50% Latino, in a state where Latinos are the biggest ethnic group. But Martinez, Cedillo and the rest also prove the limits of ethnic politics.

Examples of politicians garnering support from groups they don’t belong to aren’t too distant. Latino and Jewish voters famously joined Black voters to elect Tom Bradley as mayor. Generations of Black residents in South L.A. have voted for a trio of Hahns to represent them — Kenneth as an L.A. County supervisor and his children Jim and Janice as mayor and supervisor, respectively. Progressive whites propelled the campaigns of newly elected Councilmembers Hernandez and Hugo Soto-Martinez alongside the Latinos who make up the majority of the districts they now represent.

In my hometown of Anaheim, the best Latino politician we had was a white Republican, Tom Tait. As mayor from 2010 to 2018, Tait worked with community activists to make life better for Latinos. He supported a lawsuit that fought for district elections to diversify the makeup of the City Council and also stood up against corporate giants like Disney and the Angels that long had too much influence on city politics.

I hope the newest batch of elected L.A. Latinos — Sheriff Luna, City Atty. Hydee Feldstein Soto and Councilmembers Soto-Martinez and Hernandez, among the most prominent — doesn’t believe their own hype and governs with humility instead of hubris.

As 2023 looms, I’m reminded of the old saying about never meeting your heroes. When it comes to Latino politicians, I’d go further. Never lionize them. They’re just politicians — no more, no less.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.