Family to sell Bruce’s Beach property back to L.A. County for nearly $20 million

Six months ago, Los Angeles County leaders signed off on an unprecedented transaction: They would return two parcels of beachfront property in Manhattan Beach to the Bruce family, the first example of the government giving back land to a Black family after acknowledging it had been stolen.

On Tuesday, the county announced a surprise twist in the historic deal: The family would sell the Bruce’s Beach property back to the county for nearly $20 million.

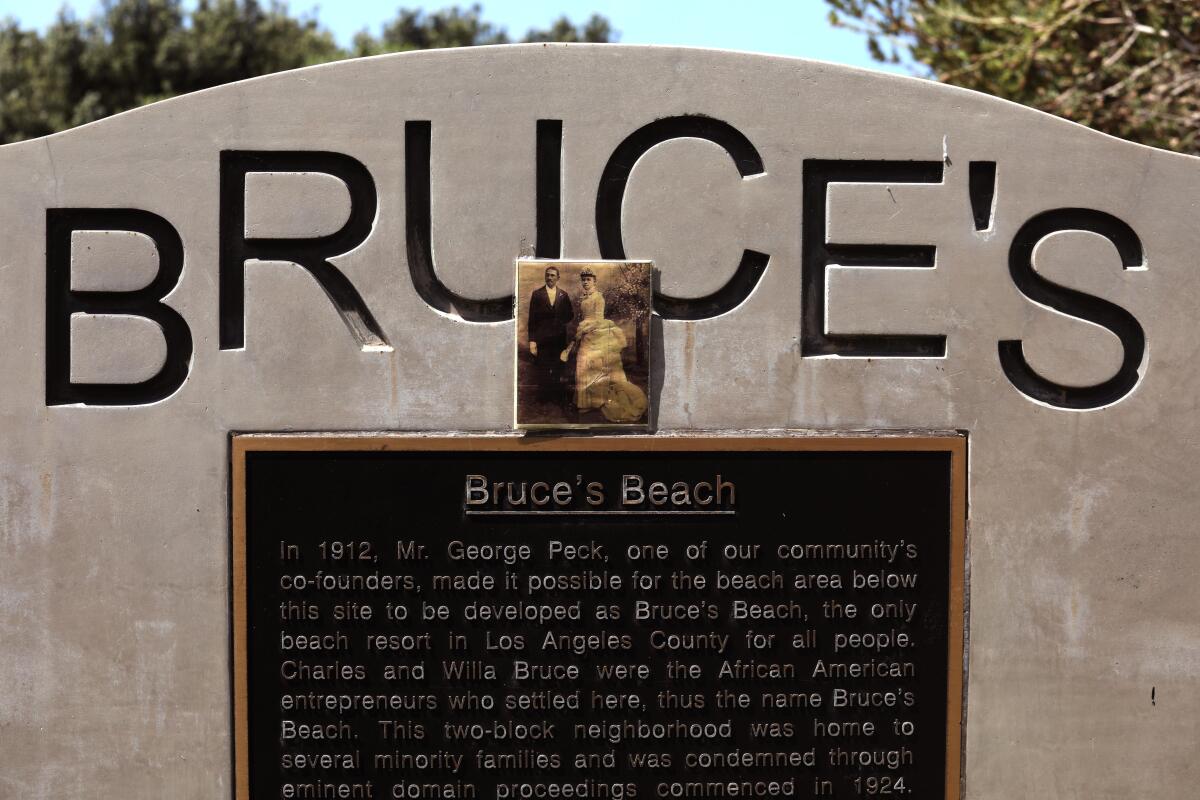

In the early 1900s, Willa and Charles Bruce were pushed out of a bustling resort they had built, beloved by the area’s Black community. The Ku Klux Klan, along with other white residents of the area, plotted to drive the family away and city officials later condemned their property in 1924 through eminent domain, claiming they needed the lots for a park. The family’s resort was demolished, and the Bruce family moved away. The park would not be built for decades.

In an effort to “right the wrongs of the past,” the board made the momentous decision in June to return the Manhattan Beach land to the descendants of the Bruces, a move celebrated nationally by reparation advocates.

As part of the agreement, Bruce family members had a two-year window in which they could require the county to buy back the property from them. They have decided to do just that.

Attorney George Fatheree, who represents the family, said in an interview the sale was not unexpected and the family had always wanted to have the option to sell the property back to the county. He emphasized the sale was still a victory for the Bruce descendants, who would no longer have the land their grandparents were robbed of but instead the money they should have inherited.

For the record:

11:39 a.m. Jan. 8, 2023An earlier version of this story incorrectly quoted a remark from attorney George Fatheree. He said, “What the property represented was the ability to create and preserve and grow and pass down generational wealth,” not “the ability to create and preserve and group.”

“What was stolen from the family was the property, but what the property represented was the ability to create and preserve and grow and pass down generational wealth. And by allowing the family now to have certainty in selling this property to the county, taking the proceeds of that sale, and investing it in their own futures — that’s restoring some of what the family lost,” Fatheree said. “I think we all need to respect the family’s decision to know what’s in its best interest.”

Fatheree said multiple factors contributed to the family’s decision. For one, he said, none of the descendants live in Southern California, and they were in stages of their life where they wanted money to invest.

He also said the land was not zoned for development, and the family members were wary of the years-long permitting fight they would need to wage if they wanted to start building.

“At the end of the day, what the family was very focused on was certainty and being able to access the proceeds of the sale,” he said.

County Board of Supervisors Chair Janice Hahn, who helped initiate the transfer, similarly characterized the sale not as an abrupt change, but as an example of reparations at work.

“They feel what is best for them is selling this property back to the county for nearly $20 million and finally rebuilding the generational wealth they were denied for nearly a century,” Hahn said in a statement. “This is what reparations look like and it is a model that I hope governments across the country will follow.”

In a heartfelt ceremony, Los Angeles County completed the historic land return of Bruce’s Beach by handing the deed to its rightful Black heirs.

The transfer of the property last year was hailed by some as a potential turning point in a nation with a long history of confiscating land from racial minorities, blocking them from the generational wealth that white residents enjoyed. Gov. Gavin Newsom, who signed Senate Bill 796 into law allowing the county to make the transfer, called the deal “catalytic.”

State Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena), who authored SB 796, said he supported the Bruces’ decision, framing the sale as the logical move given zoning requirements he said barred the family from fully developing the property. Currently, he said, it’s zoned only for public use.

“It’s bittersweet. I’m excited about the fact that the family can reap some monetary benefit from property that should have been in their family for 100 years had it not been stolen, but it’s disappointing that the family came to the conclusion of having to sell the property because they saw no long-term financial benefit,” he said. “I think they just saw the writing on the wall and said, ‘Hey, we might as well sell it right now while the market’s good.’”

Though surprising to some who cheered the Bruce’s Beach transfer as a rare reparations success story, a sale back to the county has always been an option. The transfer agreement the two parties hashed out last summer contained a two-year window in which the family could require the county to buy the land back for the value of the property — roughly $20 million. The county said in a statement the buyout option was put in the agreement at the family’s request.

A county team that worked alongside an attorney for the Bruce family conducted an economic analysis to determine the property’s value.

The county maintains a lifeguard training facility on the property. Since the property was transferred last summer, the county had been leasing it from the Bruces for $413,000 a year.

The parties have until the end of January to close the sale, according to Fatheree.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.