UCLA Chancellor Gene Block to step down after boosting enrollment, diversity, rankings

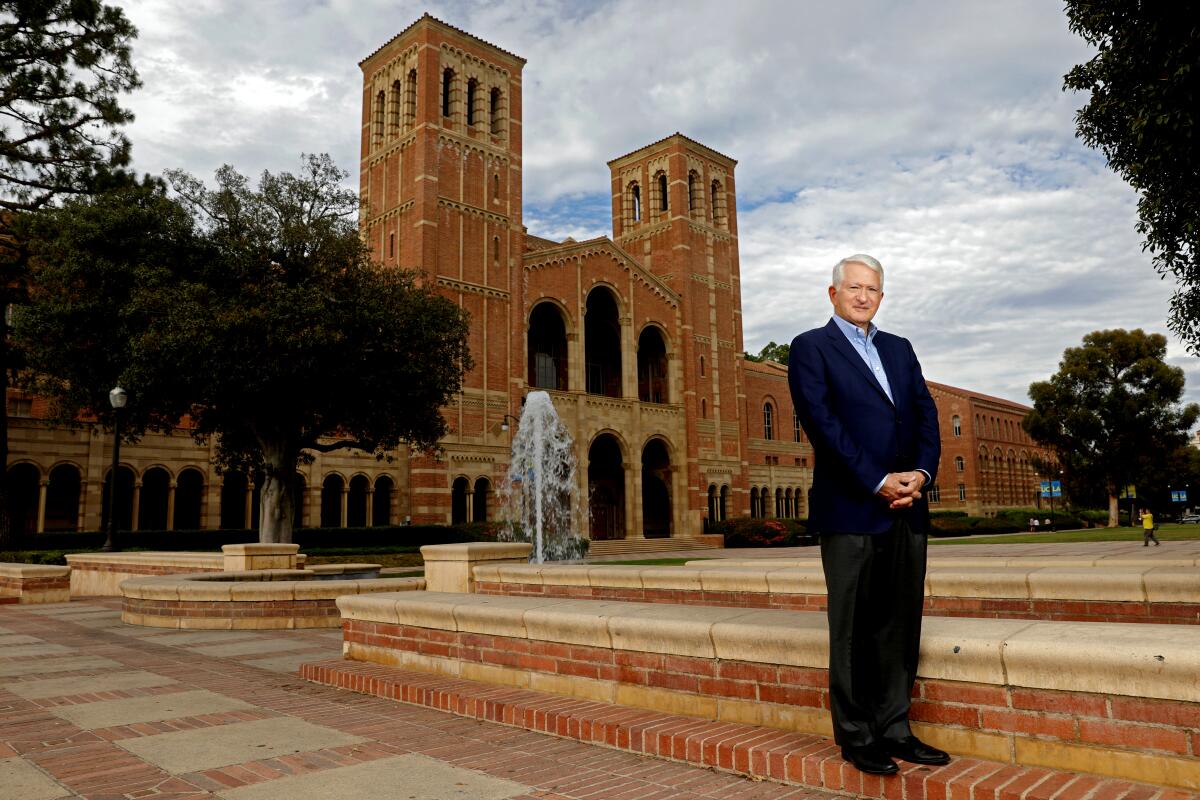

UCLA Chancellor Gene Block announced Thursday he is stepping down from the helm of the nation’s top-ranked public university after steering the Westwood campus through a financial crisis and global pandemic to reach new heights in expanding enrollment, diversity, philanthropy and research funding.

His tenure was also rocked by a huge sex abuse scandal involving former UCLA gynecologist James Heaps, which resulted in a $700-million settlement to hundreds of former patients, and controversy over leaving the Pac-12 for the Big Ten.

Block, 74, said he is eager to return to his UCLA faculty position as a researcher in sleep cycles and circadian rhythms — which he called his primary identity — when his 17-year chancellorship ends on July 31, 2024. Until then, he will help launch two new satellite sites in downtown L.A. and San Pedro, hire more diverse faculty and lay the groundwork for an ambitious new fundraising campaign.

“I’m going to miss all of the people that I work with ... that level of excitement of being at the helm of a great institution,” Block said in an interview this week. “But you can’t do this forever. It just seemed like a good time to leave the ship when the ship was sailing.”

Block’s impending retirement, which follows a similar announcement by UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ last month, will leave the top posts at the nation’s two most renowned public research universities open at the same time — a pivotal opportunity for the University of California to advance its mission with a new generation of leadership.

Block said he “absolutely” believes UCLA’s next leader should reflect the state’s diversity, shaking up the status quo of older white men who have led the campus since its founding in 1919. In fact, soon after arriving, he directed that a display of chancellor portraits be taken down because their homogeneity “sent the wrong message” about UCLA’s mission and values. The UC Office of the President and Board of Regents will soon launch a national search for his successor.

A ruling against affirmative action in admissions has renewed scrutiny over special treatment for children of alumni. USC and Stanford are potential targets.

UC President Michael V. Drake praised Block for helping UCLA grow into a “powerhouse of excellence, opportunity and access.”

UC Board of Regents Chair Rich Leib lauded the chancellor’s commitment to widen access to the most applied-to university in the nation and increase support for underserved students. Leib said he particularly valued the push by Block and his team to become the first and only UC campus to offer a four-year housing guarantee for first-year students and a two-year guarantee for transfer students at a time of severe shortages of affordable housing that have pushed many of them into unstable living arrangements. UCLA has added more than 10,000 student beds since 2007, a 77% increase.

“He’s been a really visionary force for UCLA,” Leib said.

But some regents who were troubled by Block’s handling of the Heaps scandal and move from the Pac-12 to the Big Ten said they see an opportunity for dynamic new leadership. Some faculty hope the next chancellor will be more focused on internal academic issues, including burnout among many who are overwhelmed by larger class sizes, demands for hybrid classes, a shrinking share of tenure-track positions and financial woes tied to rising costs of academic workers that administrators are not fully covering.

When first approached about the job, Block’s first reaction was quintessentially L.A. — the hassle of snarled traffic on the I-405. He had traveled to the region annually and always dreaded rush hour. But he was excited by the possibilities at UCLA. The New York native attended Foothill College in the Bay Area, earned an undergraduate degree in psychology at Stanford University and, later, his master’s and doctorate at the University of Oregon. He spent more than two decades at the University of Virginia, first as an assistant professor of biology and last as vice president and provost.

Block said he was impressed by UCLA’s size, scope and research enterprise. The largest of the 10 UC campuses, UCLA educates 46,000 students and employs nearly 5,500 faculty. External research awards have grown by 88% from $914 million in 2007 to $1.7 billion in 2023. UCLA runs a medical school, several hospitals and primary care clinics throughout Los Angeles.

But it was the students — and their diversity — that sold him, he said. At the time, one-third of undergraduates were the first in their families to attend college, as he was, with many who were low-income or transfer students from community colleges.

He soon saw that UCLA had much more work to do on racial diversity after Proposition 209 banned affirmative action in 1996 and the numbers of Black and Latino students plunged. Black first-year students dropped from 236, or 6%, in 1996 to a low of only 101, or 2%, in 2006.

As the Supreme Court weighs affirmative action, the University of California’s struggle with diversity since a 1996 ban offers lessons.

Expanding diversity became one of Block’s major goals. He directed his staff to build on earlier efforts to shift to a comprehensive review system instead of an academic index of test scores and grades. He put together a team to revamp the campus admissions strategy to help prepare middle and high school students for competitive college admissions and recruit students in diverse communities. The effort costs UCLA more than $2 million annually.

Today, underrepresented first-year students are a larger presence today than before Proposition 209 — 480, or 7%, for Black students and 1,338, or 21%, for Latinos.

One of his biggest regrets, he said, was not moving more quickly to increase Latino representation. UCLA is now working to become a Hispanic Serving Institution, a federal designation that qualifies campuses for certain grant funds if Latinos make up at least 25% of the student body. They made up 22.5% of all students and 25.3% of undergraduates in fall 2022.

Eric Esrailian, a UCLA faculty member in gastroenterology, said Block’s “big tent” commitment to inclusion included his support of Armenians. Block traveled to Armenia with Esrailian and supported the establishment of Armenian programs in human rights and research about the 20th century genocide despite protests from those who denied it occurred.

“He said, ‘We’re on the right side of history,’” Esrailian said. “I’ll never forget it.”

Block also wanted to put UCLA on a sounder financial footing. After the Great Recession hit in 2008, the state slashed funding to UC by $1 billion, one-third of its support. He and then-Provost Scott Waugh scrambled to respond, resulting in what then was the largest fundraising campaign ever launched by a public university, which netted $5.5 billion by 2020.

The campus also moved to raise funds by enrolling more out-of-state and international students to offset declining state funding with revenue from nonresident tuition, which is higher. The move drew harsh criticism from California residents who argued their education should come before outsiders.

Community college graduates in healthcare fields can outearn humanities students even from elite universities such as Stanford, UC Berkeley and UCLA, underscoring how much majors can matter.

The rise in nonresident students is one reason the number of California undergraduates has grown more slowly than the overall enrollment increase of 24% since 2007. But UCLA is now stepping up California enrollment, after lawmakers, under pressure from constituents, approved funding to buy out about 300 nonresident seats annually and give them to state residents instead.

Those rocky years presented Block with some of his greatest challenges — and opportunity to practice what his colleagues call a calm, collaborative style marked by a willingness to listen.

As UC approved major tuition increases in 2009 during the Great Recession, campuses were roiled by furious student protests, including violent clashes involving police at UC Berkeley and arrests at UC Davis. At UCLA, Block was confronted by a prolonged sit-in outside his office and advice to have the students arrested or thrown out. He and his student affairs team rejected that approach as “not a smart move,” Block said. After continued talking and listening, the students cleaned up their area and peacefully dispersed, he said.

“If you really listen ... you’ll always make a better decision,” Block said.

Block said the pandemic was even tougher to manage as the campus shut down, moved to remote teaching and faced the sudden loss of critical revenue from dining and housing facilities. He said he is proud of the decision to not lay off anyone but questions the impact of remote learning and working from home.

“One of the reasons Gene was successful for so long is that he was very careful, very deliberate and maintained an even keel,” Waugh said. “You can never please all the people all the time, but he didn’t let it faze him with the punches and tried to get the job done.”

Block said one of his most “painful moments” at UCLA came over the sex abuse scandal involving former gynecologist Heaps, who was sentenced to 11 years in prison in April. He ordered an independent review when it surfaced that UCLA Health, which is under his authority, had allowed the gynecologist to quietly resign in 2018 without informing the public of the allegations. Block said at the time the university was still investigating the allegations, but he acknowledged the campus could have relayed information about the case more quickly. He said he was hopeful that greater training, reporting protocols and other reforms at UCLA Health would guard against future abuse.

He said controversy over UCLA’s decision to leave the Pac-12 was a “tough ride” but that it was the right move for the campus, which has brought home 121 NCAA championships and 289 conference championships. The decision delighted many Bruins but outraged others, including Gov. Gavin Newsom and some regents who were upset that they had not been informed well in advance.

Critics were especially livid that UCLA’s departure would leave UC Berkeley in a greatly diminished conference, exacerbating its athletic program’s financial struggles. The regents ultimately approved the deal after requiring UCLA to share some revenue with Berkeley and take measures to support the health and academic needs of its athletes.

“We have extraordinary student-athletes and we’ve got to give them the best possible chance of being successful. I’m not regretful,” Block said.

Block appears to be popular with many students, who call him “Daddy Gene” and pepper their Facebook group, “UCLA Memes for Sick AF Tweens” with Block photos. Former undergraduate President Robert Blake Watson, who graduated in 2020, said Block was always open to student voices and began scheduling a weekly meeting with him during the pandemic to stay on top of their concerns. Watson added that Block encouraged and supported student initiatives, including a successful attempt to support a basic needs center offering clothes, hygienic products and school supplies.

Naomi Riley, a former undergraduate president who graduated in 2021, said she was gratified by Block’s support of Black students like her. He widened access for more Black students, she said, and approved a Black Bruins Resource Center that has served as a comfortable space for them with academic, cultural and social activities.

As he looks forward to returning to research, the expert in sleep cycles said he is working to reestablish his own ideal daily rhythm disrupted by the pandemic: sleep at 10:30 p.m., rising at about 6:30 a.m. for a light breakfast, a scan of the news and a 45-minute treadmill workout before reaching his office by about 8:30 a.m.

But Block said there is still much to do before moving on. This week, for instance, he plans to meet with students for a leadership seminar at UCLA South Bay, property purchased last year from Marymount California University that Block hopes can eventually accommodate 1,000 students and, along with the new UCLA Downtown site, extend the reach of the Westwood-based campus. He is eager to help plan a new fundraising campaign, an activity he said he enjoys as a way to reconnect with old friends and meet new ones while sharing UCLA’s story. And he’s excited about initiatives to increase faculty members who study Black, Latino, Native American and Pacific Islander communities.

“I’m going to stay busy,” Block said. “It’s a real honor to be able to be here and serve.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.