After secret recording emerged, a plea deal freed him. Now he’s accused of killing 3

The intersection of Century Boulevard and Vermont Avenue was a scene of carnage.

A T-boned black Honda Accord, two women dead in the back seat. A third woman dead in the roadway. A purse, a backpack, Beats headphones and a bloodstained pair of Nike sneakers strewn across the intersection.

Perched on the center median was a white Mercedes-Benz sedan, its speedometer stuck on 85 miles per hour, according to a police report.

Later that August day, Los Angeles police disclosed a startling fact: The man accused of plowing the Mercedes into the Accord, Gregory Black Jr., was on probation in a murder case.

A plea deal had sprung Black, 31, from jail two years ago, after the case against him was roiled by revelations that a sheriff’s detective had bugged a courthouse lockup without a judge’s knowledge or approval, according to transcripts and court records.

Charged with murder, conspiracy to commit murder and attempted murder, Black pleaded guilty to a single count of attempted murder — stemming from a different shooting altogether — midway through a hearing on the detective’s conduct. He was released that day, records show.

Black was not alleged to be the shooter in either the murder or the attempted murder, and the prosecutor who negotiated his plea said it was issues with the evidence — not the detective’s conduct — that led to Black’s prison-free sentence.

But a review of court transcripts and law enforcement records revealed the lockup incident wasn’t the only controversial step the detective took to secure evidence against Black and his co-defendants. He arrested a woman, her two daughters, the godmother to her children and finally her defense attorney, alleging they were embroiled in a convoluted conspiracy to tamper with witnesses in the case.

Taken together, the records show the lengths to which one officer went to convict a group of suspects he was convinced had committed murder — and how those tactics may have backfired when they came under scrutiny.

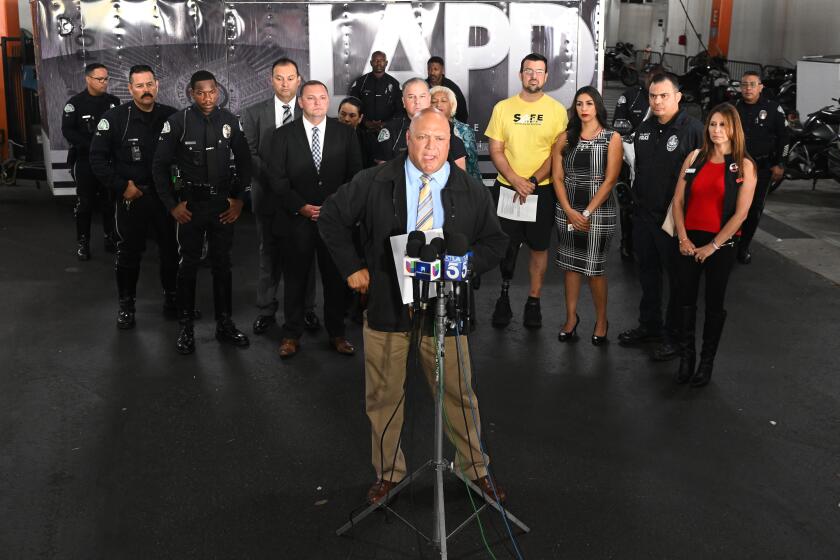

Gregory Black, accused of killing three people when he crashed into their Uber in South L.A., was free on probation in a murder case, police say.

The lockup recording yielded no evidence against Black. What it did capture was the detective denying Black’s repeated requests for his lawyer, records show, and it opened up the prosecution’s case to attack by defense attorneys. The witness tampering arrests netted four misdemeanor guilty pleas, and a rejection from prosecutors who found there wasn’t enough evidence to prove the lawyer had committed a crime.

Two years after taking the deal, Black was on the street early on a Saturday morning, barreling toward an intersection behind the wheel of a speeding Mercedes.

A bugged lockup, a ‘windfall’ for murder suspect

Jayson McKinley, 32, was parked outside his mother’s home in Willowbrook the morning of May 2, 2020, when a burgundy Buick pulled alongside. A man stepped out and shot McKinley to death, according to a police report.

McKinley’s homicide was assigned to Det. Francis Hardiman. A 30-year law enforcement officer, Hardiman has handled many high-profile investigations for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, including the homicide case brought against Marion “Suge” Knight and the murder of a Los Angeles Police Department officer last year in South Los Angeles.

The morning of Aug. 13, 2020, Hardiman arrested Black, a reputed member of the PJ Watts Crips called “Taco,” on the 10th floor of the Compton courthouse. Implicated not only in the killing of McKinley but an attempted murder in the Jordan Downs housing project, Black was placed in a holding cell inside a courtroom’s lockup. Held in nearby cells were his three co-defendants: Horace “PJ Wayne” Shanklin, Catrina “Hurricane” Briggs Bradley and Kenneth “Head Busser” Bragg.

What happened next wasn’t disclosed to anyone — not prosecutors, the judge or Black’s attorney — for seven months. In March 2021, Hardiman notified the deputy district attorneys prosecuting Black that he’d secretly bugged the lockup, hoping to get Black talking about McKinley’s murder on tape.

Hardiman said he’d simply forgotten about the 74-minute recording, which had been filed under the wrong case number.

Superior Court Judge Michael Shultz, whose courtroom was attached to the bugged lockup, ordered Hardiman to testify about the recording.

“If there’s any ambiguity as we move forward,” he told the detective, “irrespective of any standing court order by the presiding judge of L.A. County, the supervising judge of L.A. County, or the supervising judge of this court, there is no audio-recording in my court, in my lockup, in my bubble, anywhere near my court, … ever, without express permission in writing from me.”

Under questioning from four defense lawyers, a prosecutor and at times the judge himself, Hardiman said his partner, Det. Michael Haggerty, had placed a microphone in a walkway between the holding cells where Black and his co-defendants were detained and an attorney-client meeting room. Asked if the microphone was “within earshot” of the attorney room, Hardiman testified, “I don’t think that you can hear anything. But it’s in the — it’s in there. It’s not big, so …”

Hardiman testified he received permission to bug the lockup from a sheriff’s captain and commander who oversaw courthouse security.

“The response from the commander was, ‘You make sure you don’t record any confidential communications,’” he recalled. “And so, I mean, my intent was not to record any confidential communications without that admonition anyway.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Hardiman testified he blocked lawyers from entering the lockup to ensure no attorney-client conversations were picked up on the “hot device.” When Black demanded to talk to his lawyer, Hardiman admitted telling him the attorney who’d previously been appointed to represent him, Mojgan Aghai, was “not your lawyer on this case.” He recalled hearing Aghai yelling to her client through the lockup’s wall, “Do not say one word!”

Aghai, who declined to comment, represented Black for the duration of his case.

Hardiman said he didn’t believe he’d violated any prohibitions on recording in courthouses without a judge’s authorization. “The individual lockups are in the purview of the Sheriff’s Department, and not of the court. And therefore it’s an exception under these rules,” Hardiman testified.

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted Tuesday to ask the Sheriff’s Department not to install audio recording devices in courthouse lockups.

In every county courthouse, posted signs make clear a judge must approve the use of recording devices. In 2018, the L.A. County Board of Supervisors ordered the Sheriff’s Department to cease operations like the one Hardiman carried out.

Hardiman said he didn’t have an “obligation” to tell any judge about the operation. Nor, the detective said, had he notified anyone in the district attorney’s office.

“Did it just cross your mind as a thought,” Shultz asked, “Hey, if I tell the D.A.’s I’m going to tape, they may tell me not to?”

“Anytime I thought about discussing something with the district attorney’s office when I was in the investigation, there is always that possibility they’ll say, ‘Hey, we don’t want you to do that,’” Hardiman answered.

Midway through the hearing, Black cut a deal: A guilty plea to one count of non-premeditated attempted murder with a gang allegation in exchange for a sentence of five years’ probation. Prosecutors dropped the charges that he murdered and conspired to murder McKinley, which exposed him to a life sentence. Black, who had been jailed by then for a year, walked free that day.

Deputy Dist. Atty. Phil Stirling, one of the prosecutors who brokered the deal, denied that the revelation of the recording had anything to do with the resolution of the case. The evidence, Stirling said in an interview, proved only that Black acted as a lookout in the attempted murder at Jordan Downs and showed he was asleep in the car used in the McKinley homicide.

“I’m a pretty go get ‘em prosecutor,” Stirling said. “I don’t give away the courthouse unless there’s an evidentiary basis for it. A guy asleep in the back seat, it’s pretty hard to prove he’s an aider and abettor.”

Stirling argued Hardiman had done nothing wrong, noting Shultz did not rule the detective’s behavior was grounds for dismissal due to government misconduct.

Contacted by The Times, Hardiman told a reporter to get permission from the Sheriff’s Department’s press office to interview him. Several hours later, Stirling said Hardiman could not comment, citing Shanklin’s upcoming trial and related civil litigation.

Eric Youngquist, an attorney who represented Shanklin through his preliminary hearing, said he was mystified when Black was granted probation.

“While it is certainly within the realm of possibility — because it did in fact occur in this incident — it’s highly unusual,” he said.

Laurie Levenson, a former federal prosecutor who teaches at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, said it was rare for a defendant facing murder charges to plea bargain his way down to probation.

“The bottom line is, I think this defendant got the windfall,” she said of Black. “And I think it was the windfall of lack of evidence in one case, questionable conduct in the courthouse recording — even if it didn’t lead to dismissal of the case — and then sort of some informal negotiating.”

“One of the problems of plea bargaining,” Levenson added, “is that it can cover up issues that should be concerning.”

‘A nation of laws and not of men’

Wiring the lockup wasn’t the only step Hardiman took in investigating McKinley’s death that came under scrutiny. In trying to link Shanklin to physical evidence from the murder scene, the detective became convinced that Shanklin’s girlfriend, her family and her attorney were conspiring to thwart his investigation.

Two months before McKinley was killed, a woman named Nyota Harris told the LAPD a masked man had chased her inside her pink stucco home on 112th Street, pistol-whipped her, stole her car keys and fired three shots at her house before fleeing with her car, according to a police report. Officers collected three shell casings from her home.

The next day, Harris called the LAPD again and admitted she’d lied. She’d been attacked not by a stranger, she said, but by her on-again-off-again boyfriend — Shanklin.

Shanklin apparently learned that Harris had identified him as her assailant. According to an affidavit Hardiman wrote in support of an arrest warrant, Shanklin texted Harris: “I got a slug with your name on it snitch.”

After arresting Shanklin on suspicion of McKinley’s murder in July 2020, Hardiman told him that whoever killed McKinley had left behind casings.

“They match the shell casings from the shooting that Nyota said you did,” Hardiman said, according to a transcript of the interview.

That afternoon, Shanklin called Harris from jail. “They putting these bullets together, that’s why I’m telling you,” he said, according to Hardiman’s affidavit. “OK, so you know what you got to do.”

When Hardiman spoke to Harris after arresting Shanklin, she denied her boyfriend had shot up her home. “I lied on Horace,” she said, according to the detective’s affidavit. “He didn’t do it! I only know that Horace didn’t do that to me.”

Five days later, Hardiman got a warrant to arrest Harris as an accessory to murder. Her alleged crime: lying to protect Shanklin.

After being arrested, Harris admitted that during an argument over Shanklin seeing other women, he punched her, tore out her hair extensions, pistol-whipped her and pointed the gun at her 10-year-old daughter, whom he threatened to kill.

With Harris in jail, her 24-year-old daughter, Shadrona Holmes, was caring for the 10-year-old. Holmes agreed to bring the 10-year-old and Harris’ 6-year-old granddaughter, who also witnessed the assault, to be interviewed, Hardiman wrote in his affidavit.

Harris called her daughter from jail and said she wanted her attorney to be present when the girls were questioned, Hardiman wrote in the affidavit.

Harris’ lawyer “told me don’t go,” Holmes said. Her mother replied: “Follow him then.”

Later that day, Harris called Lawanda Walton Gonzales, who described herself to detectives as godmother to Harris’ children. In the jail call, Walton Gonzales said Harris’ attorney, Naren Hunter, had told her: “Do not, I repeat, do not meet up with them kids with those detectives on Wednesday, because they will try to take them.”

After confronting Holmes outside her apartment, Hardiman and his partner arrested her on suspicion of obstructing a peace officer. The 10-year-old girl was located at her father’s home and interviewed by a “forensic interview specialist,” but Hardiman still wanted to question Harris’ granddaughter and her 5-year-old grandson.

Walton Gonzales agreed to make the children available, but an hour before the scheduled meeting, Hardiman wrote, she texted the detective that she “did not want to be in the middle of the situation.” Another family friend brought the children to the Sheriff’s Department’s Homicide Bureau, where they were taken into custody by the Department of Children and Family Services, Hardiman wrote.

Hardiman then arrested Walton Gonzales, who would be charged, along with Harris, Holmes and another of Harris’ daughters, Breonna Holmes, with six felony counts of conspiring to dissuade witnesses.

Then the detective swore out an affidavit alleging Hunter, the defense attorney, had kick-started the plot. Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Ricardo Ocampo signed the warrant, setting Hunter’s bail at $1.3 million, records show. He also authorized Hardiman to seize and search the lawyer’s phone, which the detective described in an affidavit as a “possible instrument” in the conspiracy.

The morning of Sept. 28, 2020, Hardiman arrested Hunter on his way into the Compton courthouse. According to a complaint Hunter has since filed in federal court, Hardiman told the lawyer in a jailhouse interview:

“It’s about justice. And, you know, as citizens of a county [we] have all agreed on a way to live and that way to live is the law. And someone like you knows that better than anyone else. Without the law, we have anarchy. And that law applies to everyone. We are a nation of laws and not of men.”

“Without the law, it’s who’s got the most guns or who’s the biggest guy. Me and him would survive in a world like that,” Hardiman said, referring to himself and his partner.

The detective told Hunter that there was “a ton of evidence that you engaged in this conspiracy, a ton.”

Prosecutors didn’t agree. In a memorandum rejecting Hardiman’s request to charge Hunter, they noted the women whom the detective arrested had no “legal duty” to cooperate with him.

“Much of the available evidence suggests the people involved were concerned that the children would be taken by DCFS,” prosecutors wrote, noting an emotional Harris told her lawyer in a jail call that the detectives were “trying to take my kids!”

Harris, her two daughters and Walton Gonzales each pleaded guilty to a single misdemeanor count of dissuading a witness and were released after serving jail terms ranging from 10 to 69 days, records show.

Breonna Holmes’ attorney, Errol Cook, wrote in court papers the case smacked of disparate treatment for the poor and powerless.

“They never would have tried such a stunt with a parent in Beverly Hills or Brentwood,” he said.

A ‘cruel and tragic’ end

At 5:21 a.m. on Aug. 26, two sisters and their childhood friend were in the back seat of an Uber after leaving a concert. The black Honda Accord was headed west on Century Boulevard, traveling through an intersection on a green light, when a white Mercedes-Benz C230 sedan slammed into it, according to police reports reviewed by The Times.

A bystander told police he went to the crushed Accord and tried to shake the women in the back seat awake. Then he realized they weren’t breathing. He went to the Mercedes, which had come to rest on the center median.

Black hobbled out of the car, his only injury a broken ankle, a police report said. The witness told officers Black seemed “possibly under the influence of something.” On the floorboard of the Mercedes, police found a loaded revolver, the report said.

The Uber driver, Rochelle Lee, survived with a broken neck and bleeding in her brain. The front passenger, Jesus Lopez, suffered a bruised kidney and injuries to his chest and back, a police report said. Veronica Amezola, 23, and Juvelyn Arroyo, 23, lay dead in the back seat. The body of Amezola’s sister, Kimberly Izquierdo, 27, was found in the roadway.

Interviewed in jail, Black told detectives he recalled getting in the passenger seat of the Mercedes, and “the next thing I remember was waking up on Vermont,” according to a police report. He has since pleaded not guilty to three counts of vehicular manslaughter.

Jose Izquierdo, the brother of Kimberly Izquierdo and Amezola and a friend of Arroyo, declined to comment on the resolution of Black’s prior case, saying he and his family wanted to “focus on our sisters and Juvelyn.”

“These are the parts of life that are cruel and tragic,” he said. “There’s a part of me that thinks one day they’re going to give me a call or reply to one of my Instagrams or come downstairs from their rooms.”

Stirling, the prosecutor who made the deal with Black, said he felt terrible for the women killed in the crash, but defended the plea and sentence as “the correct thing to do in the situation based on the facts we had.”

“It was the right decision at the time,” he said. “Hindsight is 20/20.”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.