California prisoners could get higher wages under new plan — but still less than $1 an hour

SACRAMENTO — For the first time in 30 years, the California prison system plans to nearly double most hourly wages for incarcerated workers, a proposal that comes amid a broader debate over prison labor and a push by progressive activists to prohibit forced labor as a form of criminal punishment.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s proposal calls for eliminating all unpaid work assignments and reducing hours for most prison workers from full-time jobs to half time. Prison officials argue that higher wages will have several benefits, including making it easier for inmates to pay back the money they owe for damage from their crimes. Fifty-five percent of inmates’ wages go toward restitution costs, according to the Department of Corrections.

“Increased pay will provide a stronger incentive for incarcerated people to accept and retain jobs,” department spokesperson Tessa Outhyse said in an email. “New wages will also help workers meet restitution payments for crime victims and save more money in preparation for release.”

Approximately 40% of California’s 96,000 prisoners have jobs while they serve out their sentences, according to the department spokesperson, doing laundry and janitorial work, as well as clerking and construction. Their wages generally range from 8 cents an hour to 37 cents an hour, depending on the skill level required for the job. The proposal calls for doubling the wage range, from 16 cents an hour to 74 cents an hour.

Although prison reform advocates have long argued that wages for incarcerated workers are insufficient, some are dubious about the proposed pay increase. They say the changes will only boost hourly wages by a few nickels and dimes, and the overall daily pay by just a few dollars.

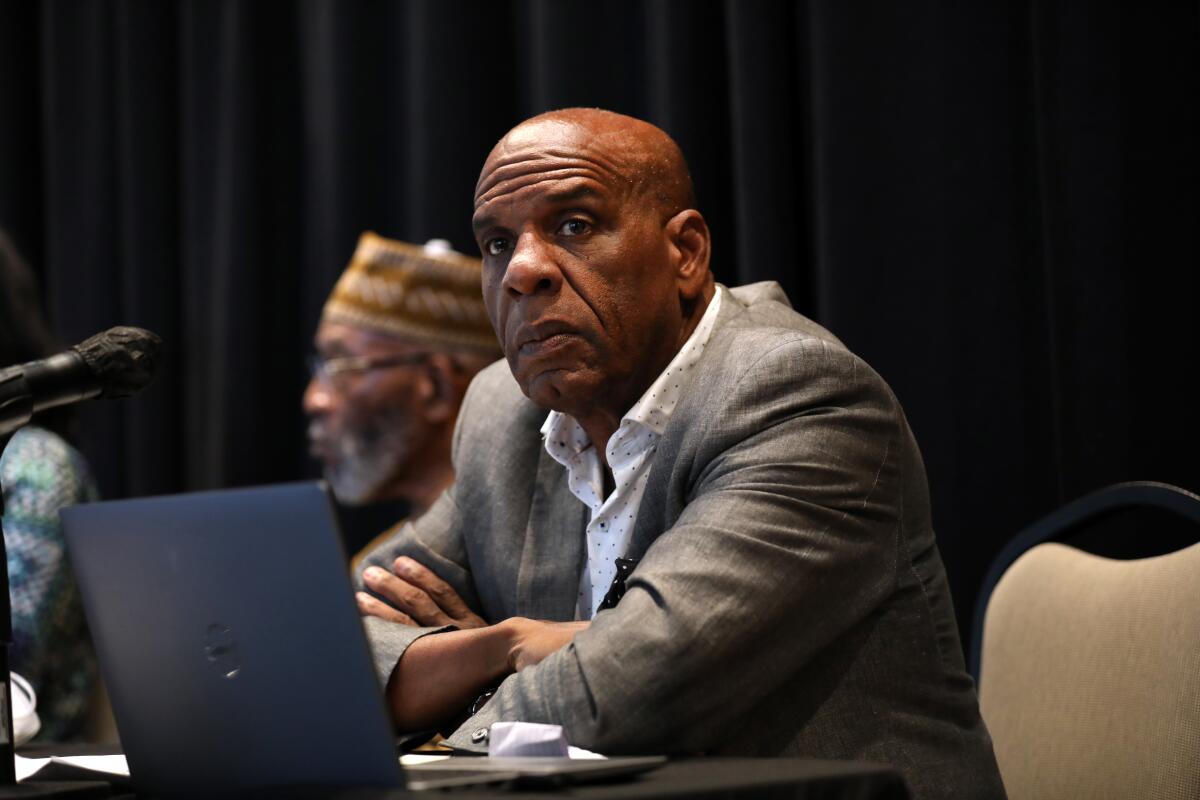

“We are not asking for a liveable wage, we are asking for a respectable wage,” said state Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena).

“It has made it increasingly difficult for incarcerated people just to provide for their basic needs in prison, be it deodorant or toothpaste, to help pay down their restitution that is owed to victims, helping their families or even staying in contact with their families using the phone.”

Bradford is a member of California’s Reparations Task Force, which recommended paying fair market value for prison labor and eliminating forced labor as a criminal punishment from the state Constitution. Lawmakers considered a measure this year known as the “End Slavery in California Act” that would eliminate a provision in the state Constitution that allows for involuntary servitude as punishment for crime. It passed the Assembly in September and may be heard in the Senate next year. If passed by two-thirds of the Senate, the change would then have to be approved by voters.

California lawmakers could let voters decide whether to ‘prohibit slavery in any form,’ which could change work requirements in prisons.

Prison officials did not respond to questions about whether the proposal to increase wages is related to the discussion about removing involuntary servitude from the constitution. But their concerns helped kill an earlier effort to pass a constitutional ban on involuntary servitude as a punishment for crime. In 2022, the Corrections Department told lawmakers that it would cost billions of dollars to pay prisoners minimum wage.

The cost to taxpayers was one reason state Sen. Steve Glazer (D-Orinda) voted against the measure last year.

“I was concerned about eliminating the word ‘slavery’ in the constitution without any detail on how it would be implemented in our prisons and would take power from legislatures to courts,” Glazer said in an interview.

He said he supports raising wages for prison workers. “But at the heart of it, it’s a budget priority choice issue,” Glazer said.

Budget projections show California is likely to face a shortfall of at least several billion dollars each of the next three years. The Corrections Department’s current plan to raise wages would not require additional funding from the state budget, spokesperson Outhyse said, because hours would be reduced while wages are increased. She said the budget allocates approximately $10 million a year for incarcerated wages and the proposed regulations “will maximize utilization of that fund.”

Assemblyman Ash Kalra (D-San Jose) said he plans to push the state to consider even higher wages when lawmakers return to Sacramento in January.

“It always sounds dramatic when you say something is being doubled,” Kalra said. “But going from 8 cents to 16 cents doesn’t really move the needle or give incarcerated workers the dignity they deserve.”

He plans to revive Assembly Bill 1516, which stalled last year. It calls for the state to study the socioeconomic benefits of ending wages below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour for incarcerated workers.

“To simply raise the wages a few pennies, certainly acknowledges the fact that there is an agreement that incarcerated workers are being grossly underpaid,” Kalra added. “But I think there is a long way to go.”

Jarad Nava, sentenced to 162 years in prison for a crime he committed when he was 17, has a second chance in life and is now working for an influential committee of the California Senate.

A portion of inmates who work in fire crews — and are based in separate conservation camps that provide intensive wildfire training — would see the greatest income hike under the prison system’s proposal, with some going from earning $3.34 per day to $6.68 per day and others from $5.12 to $10.24 per day.

One category of workers would not receive a pay increase under the plan: About 5,700 inmates hired by the California Prison Industry Authority, a separate employer within CDCR, who are paid on a different wage scale. They work manufacturing jobs that create products such as eyeglasses, office furniture, shoes and license plates that are then sold to state departments. At the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of these workers churned out face masks for the general population.

At a news conference Nov. 16, hosted by the Living Wage for All Coalition — a nonprofit group focused on ending sub-minimum wages — advocates and lawmakers criticized the Corrections Department’s wage increases, arguing that the changes are “unethical” and “unjust” because they do not meet rising inflation or ensure living wages.

Shone Robinson, who was incarcerated for 22 years, said at the news conference that paying restitution while incarcerated was “a large hurdle.” Robinson was convicted in Riverside County of second-degree murder and testified that she acted in self-defense, the Press-Enterprise reported in 1997. Released from prison in 2017, she now works as a life coach at the Anti-Recidivism Coalition.

“Not only did I pay restitution, but I also had to start my life beyond prison walls. Being locked up at a very young age did not prepare me for what I had to face,” Robinson said.

The wage increase was proposed as a new regulation of the state prison system and can be approved after a period of public review that ended last week.

Jeronimo Aguilar, a policy analyst for Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, told The Times that he questions whether inmates will just earn the same amount, or even less, as a result of the changes from full-time to half-time work. He also speculates that the state might end up saving money.

Ultimately, however, he said he doesn’t want to “just blindly oppose this new regulation.”

“We don’t want folks inside to think we’re opposing it because we want more,” he said. “We might kill an opportunity for them. Going from 8 cents to 16 cents may not be a lot for us, but for an indigent [worker] that’s huge.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.