New tool to reduce homeless camps: L.A. County leases apartment building for former RV dwellers

Looking back, life in the RV camp wasn’t all bad.

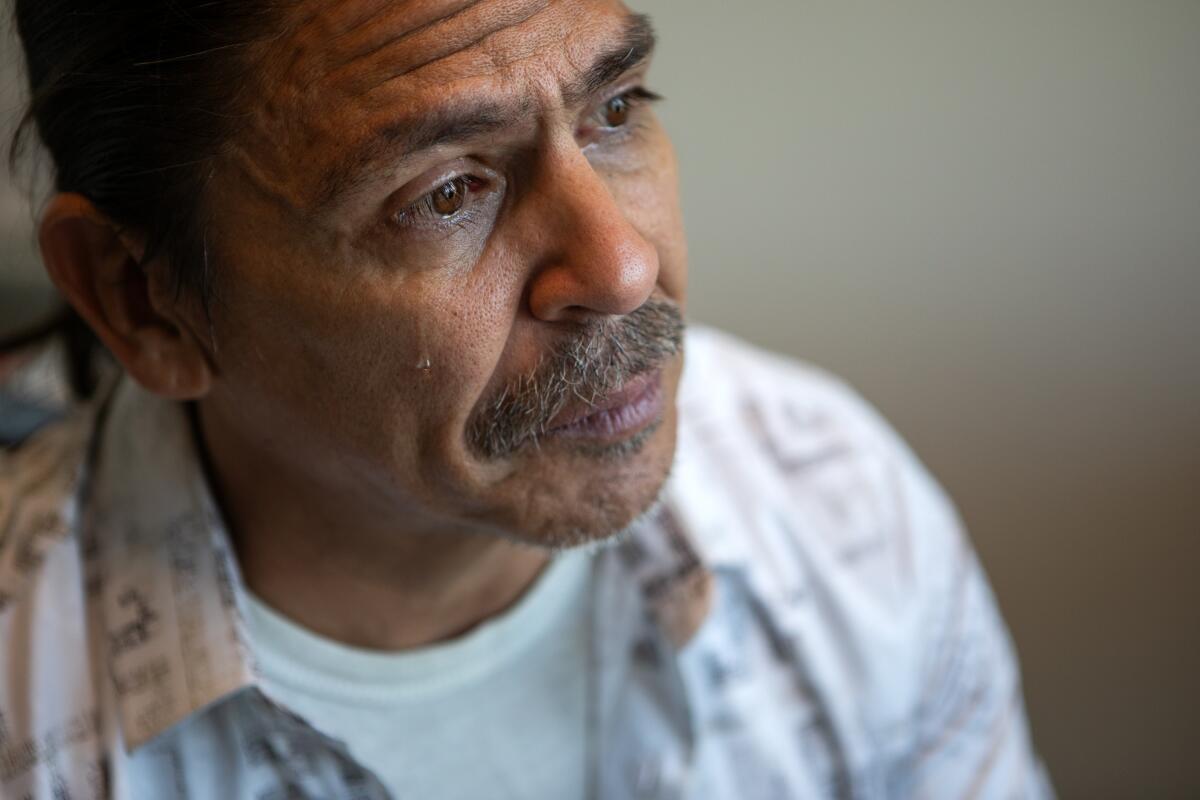

There were some good people living in the clusters of RVs scattered throughout unincorporated Gardena. For Robert Almorejo, it was a community where everybody knew everybody. He earned money painting his neighbors’ RVs. There was a stake of a sort: he owned his own home. And there was one dear friend, Jessica.

But then he remembers the cold days with no heat, the hot days with no air conditioning, the stove with no gas.

“This right here is a lot easier,” he said. “It was worth it.”

“Right here” is the apartment Almorejo moved into last week.

He was one of 20 former residents of a Gardena encampment who agreed in August to surrender their RVs and move into a motel with a promise that they would be on track for permanent housing. Three months later, that promise came true as they were welcomed into a new four-story building in unincorporated Florence-Firestone.

They were the first cohort in L.A. County’s counterpart to Mayor Karen Bass’ Inside Safe program. Since its kick-off in August, the county program, called Pathway Home, has conducted five camp cleanups, which it calls “resolutions,” moving 230 people indoors and taking 122 RVs off the street.

As L.A. officials and residents push to get rid of RV encampments, one woman’s story reflects the mountainous obstacles faced by those who try to find housing.

“This is just the start,” said Cheri Todoroff, director of the county’s Homeless Initiative. “We are going to keep on, working up to a scale of doing multiple encampments each month.”

Key to the program is lining up apartments so that those who accept temporary shelter don’t languish in motels. It’s a vexing problem that has so far limited the success of Bass’ Inside Safe, which as of mid-October had placed more than 1,682 people in shelters but only transitioned 190 into permanent homes.

One answer, which the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority is pursuing for both the city and county, is to search out landlords who are willing to hand over the keys of whole buildings for lease. By obtaining what is called a master lease, the city or county can move people in quickly, bypassing credit and background checks that are obstacles in the private rental market.

The agencies assume operating costs including management fees, insurance, maintenance, pest control, security and vacancy losses.

Because of those costs, and their unpredictability, master leasing has not been widely used by the nonprofit organizations that provide homeless housing and services, said Kris Freed, a consultant for LAHSA.

Almorejo’s new home on Firestone Boulevard is the first instance of government in L.A. County entering into a master lease, Freed said.

Many more will follow, officials say. LAHSA is currently negotiating several other leases. Half the rooms, when available, will be turned over to the city, county and a state agency for street cleanup programs, Freed said. The other half will be allotted to people already living in shelters.

Todoroff said the county aims to secure 1,700 units by the end of 2024, still a small fraction of the more than 22,000 estimated in 2023 to be living on the streets outside the city of L.A.

The costs will be borne with $55 million in state Housing and Homelessness Incentive Program funds funneled to the county by health plans L.A. Care Health Plan and Health Net.

With that backing, LAHSA can enter into multi-year leases to provide long-term stability. The funding doesn’t cover rents or services.

Measure H, the county’s quarter-percent sales tax for homelessness programs, will pay for services.

Rent will come from a variety of sources. Some tenants will have federal or local vouchers or will receive short-term subsidies while applying for vouchers. Others may have enough income through disability or jobs that they only need what are called shallow subsidies to pay the difference.

Because the county controls the leases, tenants who get jobs and can pay their own way don’t have to move out, an essential element to the program, Freed said.

“We need folks that are able to pay their portion,” Freed said. “With that you can scale this. Without people paying their portion there is a ceiling to how many you can bring in.”

For the county, the challenge of obtaining permanent housing is compounded by the need to apportion its efforts over more than 80 cities and a tangle of unincorporated areas between them.

“We are being thoughtful about how we are identifying the areas to prioritize,” Todoroff said.

Preference goes to areas that are disproportionately impacted by poverty and where homeless camps are causing harm to neighborhoods and where the county has strong relationships with service providers.

The first cleanups were in Lennox, Hawthorne, Pomona and twice in Gardena. More will be coming to Gardena, where extensive RV encampments became established during the pandemic.

Tenants from the first cleanup who were settling into their single apartments, in the days before Thanksgiving, described a feeling of disbelief overcome by gratitude.

“Overwhelming, a place to call my own,” said William Escribano, a Cudahy native who said he paid a street broker $350 for an RV — without a pink slip — because he was tired of living on the streets.

Escribano said he long resisted offers from outreach workers from St. Joseph Center to trade his RV for a shelter.

“I wasn’t interested,” he said.

Then a sheriff’s deputy told him his RV, which had not been tagged since 2017, was going to be impounded.

Having a real home for himself and his canine companion Dabs has put his former life into perspective.

“Before I had him, it was pretty scary,” he said.

Friends were not necessarily dependable. “They act like it for a certain time, then they can be your worst enemy.”

He couldn’t work at his occupation as a truck driver. When he was away, his things would disappear, and “Nobody sees anything.”

Now he feels like he’s in a dream, that is “not really happening.”

A few doors down on the fourth floor of their new home, Almorejo was more pensive.

He feels bad for those left behind, especially Jessica, who has been disowned by her family and is too stuck in her ways to accept help.

“She’s got her trailer,” Almorejo said as a tear ran down his cheek. “It’s not the greatest trailer in the world, but she doesn’t want to leave it. It’s her home. It’s her first home. Hard for her to leave it behind.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![Los Angeles, CA - May 19: Carlos Vargas, left, and Paulina Rubio, members of the harm reduction team from Homeless Outreach Program Integrated Care Systems [HOPICS], a leading homeless services and housing agency, look for drug addicts to help and pass out supplies at a homeless RV encampment along 77th St. in South Los Angeles Friday, May 19, 2023. The team hands out syringes, fentanyl test strips, overdose reversal nose spray and medication to prevent overdoses, infection and disease transmission, including the HIV virus. Fenanyl is particularly insidious because it can be found in all other drugs, especially meth and heroin. The handouts are also meant to reduce infection through broken pipes, which can cut users mouths and open them to infection. . (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/530e2db/2147483647/strip/true/crop/3900x2608+0+34/resize/320x214!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fe9%2F77%2F4b8bd35d4881a3edec6b945b143b%2F1298639-me-soaring-fentanyl-deaths-24-1-ajs.jpg)