Is your student still struggling with pandemic setbacks? A state legal settlement offers help

A landmark settlement announced Thursday sets new accountability rules for how California public schools are to spend $2 billion to help students recover from pandemic learning setbacks: Educators must rely on proven academic strategies and track progress, which will be publicly disclosed — and if parents are not satisfied, they can file complaints.

The agreement brings an end to sweeping litigation that dates from the fall of 2020, when students were learning remotely from home, with campuses closed because of safety concerns. The lawsuit was silent on the merit of school-based COVID-19 safety measures and campus shutdowns. But it argued that students fell behind during online schooling and the state was not doing enough to remedy the harm.

Attorneys sued the state Board of Education, the state education department and Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond on behalf of students and parents and community groups in Oakland and Los Angeles.

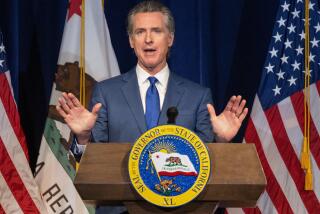

Officials including Gov. Gavin Newsom and state Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond have repeatedly defended California’s efforts as thoughtful and generous. They pointed to billions of dollars in state aid for computers, COVID safety measures, academic help and mental health support as well as early access to vaccines for teachers and other school workers.

In the settlement, the state admits no wrongdoing. The California Department of Education, led by Thurmond, views the agreement as an opportunity to “double down on” its work, a spokesperson said.

State Board of Education President Linda Darling-Hammond said the pandemic has worsened the lives of many students.

“The needs have grown only greater since the height of the pandemic, with more California students living in poverty ... and an increasing number experiencing homelessness,” she said.

California’s efforts to date, “resulted in the state losing less ground than most other states in math and holding steady in reading on national tests from 2019 to 2022, and in reducing chronic absenteeism more rapidly than most others. But there is a long way to go to fully recover from the pandemic.”

The settlement terms are “appropriate,” said Alex Traverso, communications director for the state Board of Education, speaking on behalf of Newsom. “We appreciate the collaborative approach and the insights that plaintiffs offered.”

The agreement comes as a report, released Wednesday, added to the body of research about the depth of harm to students in California and throughout the nation, starting from the pandemic’s outset in about March 2020. The latest research indicates that recovery is lagging. These researchers reached different conclusions on California’s progress than Darling-Hammond, in some instances focusing on different data.

Students in 17 states, including California, remain more than a third of a grade level behind 2019 levels in math. Students in 14 states remain more than a third of a grade level behind in reading. Although California’s English language arts scores were high enough to avoid this list, its scores actually got worse from 2022 to 2023 on state tests, despite students being back on campus, stated the report, titled the Education Recovery Scorecard.

Overall, academic recovery in California had “barely begun” as of spring 2023, according to this ongoing research, a collaboration between the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University and the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University.

The state’s worst performing schools improved after ‘science of reading’ reforms, using phonics, were paired with ongoing support, analysis and parent buy-in.

Moreover, the academic setbacks were larger in high-poverty districts such as San Bernardino, Bakersfield, Fresno and Long Beach, where achievement fell by more than two-thirds of a grade level in math and more than a third of a grade level in reading, the report said.

“Educational outcomes are more unequal now than in 2019,” said Stanford professor Sean Reardon. “If California state and local education policymakers don’t act soon and decisively, that inequality is likely to become permanent.”

“No one wants to see poor kids footing the bill for the pandemic, but that is the path California is on,” said Harvard professor Thomas Kane, speaking of the effectiveness of state efforts before the settlement. “With federal relief dollars drying up, state leaders must ensure the remaining dollars are used for summer 2024 and for tutoring and after-school next year.”

The state funding is not new. It was previously set aside, as part of the 2023-24 budget, for pandemic recovery. School districts already have the money, but have not yet spent major portions of it. The settlement overlays a detailed structure for how this money must be used — with the intent of reaching more of the students most in need — and with more safeguards.

In addition, there are new rules to hold schools and school districts accountable, including making the spending plans and their results more transparent to parents and the public.

Billions of dollars in state and federal pandemic relief have yet to pay academic dividends with K-12 students, although officials remain optimistic.

“This settlement has some strong accountability measures that should help ensure students get the resources they need,” said attorney Chelsea Kehrer of Morrison Foerster, which filed the suit in tandem with the public-interest law firm Public Counsel.

The settlement will rely on a process that already exists but remains obscure outside education circles. It’s called the Local Control and Accountability Plan. These plans were part of reforms, led by then-Gov. Jerry Brown, that poured more resources into schools and students with high needs — including Black and Latino students, those from low-income families and students learning English.

Broadly speaking, that’s also the intent of the settlement. Schools must explain how their recovery spending will contribute directly to a positive outcome, such as higher test scores or improved attendance.

Settlement rules also require school districts to use the money to help the most hard-hit or poorly performing schools or student groups.

A new federal report lends support for providing better oversight of school-improvement plans. In its sample, the federal review found that less than half of school-improvement plans had components widely considered necessary to be successful. A good plan is supposed to include an examination of needs, assessing where and how resources are unfairly distributed and identifying proven strategies that will be used to help students.

Because the settlement makes changes to how state money is to be spent, the Legislature’s approval of the agreement is required.

Under the settlement, the total funding available must reach at least $2 billion statewide. If it doesn’t, the state must devise a plan to make up the difference, which could require action from the Legislature. If the pieces don’t fall into place, the settlement would unwind.

So far, however, advocates are confident that at least $2 billion is available in unspent funds for the state’s nearly 1,000 school districts.

The money is likely to be available because school systems have tried to stretch out the use of pandemic aid for as long as possible as they sound alarms about upcoming budget problems that could result in reduced services and layoffs. Los Angeles Unified, for example, has tracked the deadlines for each tranche of state and federal pandemic aid, spending the money with the earliest deadlines first.

For a while, so much aid was flowing in that districts had trouble spending it, unable to hire extra teachers, tutors and mental-health workers. But that surplus period is drawing to a close.

“If they were waiting for a rainy day, they need to be reminded that California’s most disadvantaged students are in the midst of a thunderstorm,” said Mark Rosenbaum, senior special counsel for strategic litigation at Public Counsel.

Absent the settlement, this $2 billion still would have been available for pandemic recovery, but with fewer rules on spending, tracking and reporting.

“At least now, there will be visibility and attention, and the uniform complaint procedure added means that anyone, including parents and caregivers, has a process to call out a district not using the resources in a timely or diligent fashion as mandated by the strategic plan,” Rosenbaum said. “So these are resources that were meant to be used as an urgent crisis dictates, and they now will be.”

At a time of declining enrollment at L.A. Unified and statewide, Porter Ranch Community School is the only LAUSD campus that’s full and turning away families.

Schools will have four years to spend the money.

If existing funds are available as expected, the settlement will have little to no effect on the impending state budget negotiations. Newsom is trying to close an estimated $38-billion deficit that looms over his proposed budget for the fiscal year that begins July 1. Total state revenues are expected to surpass $291 billion.

The original lawsuit focused on harms to students as they were occurring during the period of remote learning.

The suit cataloged children’s lack of access to digital tools as well as to badly needed academic and social-emotional supports. The suit also alleged that students were harmed by schools that failed to meet required minimum instructional time and to provide adequate training and support to teachers.

Angela J., a plaintiff named in the complaint and a parent of three elementary-age children in the Oakland Unified School District, said that her twins, who were in the second grade at the onset of the pandemic, received live instruction with a teacher only twice from the time when schools closed in mid-March 2020 to the end of the school year. The students weren’t assigned packets or other materials to make up for the lost time.

Once in-person learning resumed, the focus of the litigation shifted to the harms that students had suffered and the adequacy of recovery efforts.

Community groups that participated in the litigation — the Oakland REACH and L.A.-based Community Coalition — provided academic and emotional support to families during the pandemic.

The Oakland group ultimately shifted from advocacy work to providing direct services — using teacher aides, parents and community members to provide off-campus and on-campus tutoring and homework help — both on its own and in collaboration with the Oakland Unified School District. The group also has provided case managers for a family’s non-academic needs.

The group sought research validation for its efforts that will make it eligible for settlement funding.

“We really work closely with our district. We have a lot to share and a lot to teach,” said Lakisha Young, chief executive of the Oakland REACH. “The settlement dollars need to be repurposed to serve kids who haven’t been served well.”

Groups similar to her own, she said, “need to show up with evidence-based work.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.